AGI isn't for happy people

Wouldn't you rather be on the be/acch?

warning: borderline chronically online

I.

Anatomically modern homo sapiens emerged around 200,000 years ago. As far as we know, complex human behaviour began around 10,000 years ago. We’re talking tools, language, the beginning of civilisation. Which has worked out well, we’ve got a lot done. But the obvious weird thing is that with the very same biological and cognitive capacities we have today, we did essentially nothing for over 190,000 years. The vast, vast, vast majority of human history … is empty.

This is the Sapient Paradox i.e. ‘why the hell did it take us so long for us to do anything?’

Vague popular answers:

We needed to hit a critical mass of people first

A genetic change we don’t know about

Language grew enough to enable cultural transmission

These never feel satisfying because they are obviously so undefinable, and just generate the why 190,000 years question again. I’m much more compelled by the story Erik Hoel told in The Gossip Trap a couple of years ago:

A 'gossip trap' is when your whole world doesn't exceed Dunbar's number and to organize your society you are forced to discuss mostly people [rather than events or ideas]. It is Mean Girls (and mean boys), but forever. And yes, gossip can act as a leveling mechanism and social power has a bunch of positives—it's the stuff of life, really. But it's a terrible way to organize society. So perhaps we leveled ourselves into the ground for 190,000 years. Being in the gossip trap means reputational management imposes such a steep slope you can't climb out of it, and essentially prevents the development of anything interesting, like art or culture or new ideas or new developments or anything at all. Everyone just lives like crabs in a bucket, pulling each other down. All cognitive resources go to reputation management in the group, to being popular, leaving nothing left in the tank for invention or creativity or art or engineering.

The evidence is that many anthropologists who studied early societies basically found the same thing - a bunch of people living in what was essentially a never-ending high school drama.

Chiefs who ruled through eloquence and popularity rather than authority, and tribal systems where material wealth couldn't be converted into formal power. Social pressure, rather than formal laws, was the primary means of maintaining order, with examples like the Hazda mocking successful hunters and Haitian peasants hiding wealth to avoid social consequences. Early forms of "money" like wampum were used to track social relationships rather than commerce, and early formal power structures were often temporary and theatrical, suggesting that raw social power was the underlying organising principle.

Now this I can pretty much buy. Progress doesn’t happen because everyone is incentivised to maintain their relative status, rather than absolute well-being. Which means that guy two caves down who’s trying to invent farming is more of a threat than opportunity. It’s a basically Teach-ian notion. Hence “doesn’t he think he’s great”. Hence ‘Gossip Trap’.

Hoel claims progress eventually does happen when the numbers grew too big for even the most powerful social influencers to control everyone, and thus the trap is eventually broken forever.

I was thinking about this while listening to old clips of the Tim Dillon show a few nights ago. Tim is one our best modern commentators, and this is one of his best ever: Some People Aren’t Built To Enjoy Life. Towards the end of the clip, he makes this observation:

Understand that what makes most people happy is their family, their friends, community, hobbies. But there’s a specific group of people who are going to be entrepreneurs, who do actually get hard for working.

If you’re out on a Saturday night, and everyone’s getting drunk and having a good time, and you’d rather be building a business, then you know maybe you’re one of these people.

If you’re at the beach and you’re getting antsy, and you’re like ‘I’d rather not be here. I wanna be at a desk working out how to make money. I’m done being in a backyard with my friends having fun.’

That’s an internal realisation some people have. Which means Gary Vee or Tai Lopez aren’t going to be the difference between you having a fucking business or not.

That’s how I felt when I got into comedy. I was done having fun in backyards. I have friends who think that’s crazy and they’re probably not wrong. They’re not wrong. I have friends who are on a beach right now that are like ‘who cares’. They are not trying to light the world on fire. They just want to enjoy their fucking life.

But some people aren’t built to enjoy life. They’re built to do things, to wanna be great at something. And if you wanna be great at something, the baseline isn’t going to be enjoyment. It’s going to be fulfilment, and you’ll never be fulfilled.

I have friends who just wanna enjoy, and that’s great. As long as they got a coconut shrimp in their mouth, and a shot of rum, and someone’s banging a steel drum, and they don’t have to work the next day - they’re good.

But Gary Vaynerchuk can’t come out and say “Guys, here’s your biggest issue, you’re built to enjoy life. That’s why you’re not succeeding. Because when you’re around other people and they love you, that’s enough. It can’t be enough guys. It can’t.”

Carnegie, Rockefeller, it wasn’t enough for any of those people. Gary Vaynerchuk should just say “the love of my wife and kids, it’s not enough for me, doesn’t get me off enough, I need MORE”, because honestly that’s what it is. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that, you need the guy that needs more because civilisation has to go forward.

My friends aren’t driving civilisation forward. They’re driving, illegally, a car.

You’re just either that person or you’re not.

This is the alternative lens I view Hoel’s Gossip Trap theory through.

Hoel writes: “The difference between the horror of crabs in a bucket and a human tribe living in a gossip trap is actually that the humans are generally quite happy down there in the bucket. It's our natural environment. Most people like the trap.”

So I say alternative because it removes the ‘trap’ sentiment entirely. For the majority of people, those 190k years of ‘nothing’ were enough, and they didn’t feel any need to mess with it. They ate, they hung out with their friends, they probably fell in love, they didn’t have work the next day. And I don’t think you can say they were wrong.

Eventually, civilisation starts from under their feet anyway. But the pattern remains.

Early Bronze Age Mesopotamia (3000-2000 BCE) was enough for most people living along the Euphrates. While kings commissioned epic poems and priests tracked the movements of planets, most folk spent their evenings telling jokes in the shade of date palms, playing board games like the Royal Game of Ur, and swimming in the river to escape the heat. They weren't trying to build empires - they had their simple pleasures and each other.

The Golden Age of the Maya (250-900 CE) was enough for the common people living in and around cities like Tikal. While their rulers were obsessed with building ever-taller temples and waging prestige wars, most Maya spent their days tending their milpas, gathering at the marketplace to trade and socialise, participating in local religious ceremonies, and enjoying pulque with their neighbors. They weren't driven to "advance civilization" - they had their families, their communities, and their traditions, and that was sufficient.

Medieval village life in 12th century England was enough for most people. They worked their strips of land, gathered for church services and feast days, shared ales at the local tavern, and participated in the harvest festivals. While nobles worried about expanding their holdings and monks debated theological minutiae, the average villager found enjoyment in their tight-knit community, seasonal celebrations, and the simple pleasures of gossip and communal bread-baking.

And what we have now is enough for most of Tim Dillon’s friends. They don’t need extreme success because they’re happy already. Gary Vee might think they’re crazy, but they have a pretty strong case for why it’s the other way around.

People often look at those correlational graphs that show people with crazy high incomes not being that much happier than everyone else, and think it means humans aren’t built to derive true happiness from money. But the real answer might be that some people aren’t built to derive happiness full stop, and those people will always need more.

From Hotel Concierge, ten years ago:

There’s a type of joke about a mid-40’s housewife who is way too well-educated and bored to be a housewife, and so she tries to find the Grail of healthy food and she plants a garden, and she adopts pets, and she joins nonprofits, and she joins the school board, and she reads every novel on NPR’s end of the year list, and she gets weekly therapy and monthly massages (to about the same effect), and she meditates on the present, and she achieves peace with the past, and she contemplates the future, and everything is feng shui, and yet, despite all this, she feels restless, anxious, unhappy, and she dreams of some sort of vacation.

Or sometimes the joke is about an elderly businessman on his second hair transplant and third cardiac stent and twenty-billionth dollar, and his kids all have grandkids and his wife is deceased, and when he goes out he he orders scotch more expensive than houses, but that isn’t too often—he’s seen enough parties, he’s seen enough people, he has no strong affections, and he works round the clock fighting tooth-and-nail for his billions, because he’s not sure what else, exactly, he’s supposed to be doing.

Or the joke is about a magazine-cover movie actress who has the adoration of thousands and still feels worthless. Or the joke is about a virginal computer science genius who has deleted his OKCupid and decided to eschew all noncoding activities. Or the joke is about a millionaire athlete under investigation for using anabolic steroids. Or the joke is about a 50-something cardiologist who hates all his patients but knows that he’d hate being retired even more. Or the joke is about a young power couple who like each other very much, love, maybe, but they’re both distracted by the nagging feeling that they could do better, that they should be shooting for something greater, and so they break up and find new partners and the process repeats again.

And the joke, which you hear on forums or sitcoms or in crowded sports bars, goes: “Haha, even though these people are successful, they’re still dissatisfied."And I’m here to tell you that this joke is totally backwards. It’s because these people have always been dissatisfied that they achieved success.

And I think these are the people who tend to drive society forward.

II.

I call Dillon a great commentator because in the midst of that monologue he pretty accurately sums up the entirety of happiness and well-being research without needing a 300 page airport book. For future reference, take this rule and use it wisely:

Given the same resources, people generally choose either a happy life or an interesting life.

This is obviously more of a spectrum than a binary, and the names you choose to give the poles will always be subjective, but I think people intuitively understand this kind of difference exists. Which one you choose does not necessarily mean you will successfully end up there, it just gives a sense of the guiding principles you live by. To get a vibe of where you live between the two, Penelope Trunk suggests test questions like these (which I found via Stella Tsantekidou), where a positive total score indicates preference for happiness over interesting-ness:

1. Did you relocate away from family for a better job or another more interesting experience? Minus one

2. Did you relocate to be near family? Plus one

3. Are you nationally recognized as being great at doing something or do you have nationally-recognized expert knowledge in something? Or are you reorganizing your life in order to achieve this end? Minus one

4. Were you a happy child? Plus one

5. Do your friends pray? Plus one

6. Do you have an opinion on Picasso? Minus one

12. Have you been to a therapist? Minus one

16. Do you think this test is BS? Plus one

While the above is a beyond rough measure, it’s no coincidence that this is a dichotomy that recurs in various forms throughout the history of psychology. Jung, for example, saw people choosing between perfection and wholeness i.e. do you want to be operating at 100% capacity at one thing, or have like 5 different things at 70% (i.e. career, friends, family, health, whatever else). This is essentially the choice you are presented with in your 20s.

And it’s a decision you kind of need to be honest with yourself with, because there are cons on both sides, and you need to know which cons you’d rather live with. For instance, real life skill-trees are lopsided. People who are world-class amazing at something tend to be almost embarrassingly bad at some basic human skills. That’s the choice they started making when they entered adulthood and continued making every day since. Worth it? To them, yes. Because wholeness isn’t their goal. And the obvious con of happiness is that is reduces the chance you will be truly great at anything. Or to phrase it like Sympathetic Opposition: satisfaction makes you stop.

(By the way, I don’t think this is fixed. Hence ayahuasca one-shotting people from end to the other. And also Ozempic incidentally killing your desire for everything. More on that some other time, maybe)

Both of these groups are useful to each other. As in, Sweden is awesome, but it’d be significantly less awesome if everywhere else was like Sweden.

I actually wrote about a similar dichotomy before from a Freudian/Nietschean perspective using the terms of ‘life-denying’ and ‘life-affirming’ people, but I will admit that it came across implying one of those is much better than the other.

So to be more balanced, let’s take the happy-interesting test and reduce it to one single measure. I present to you the Tim Dillon Happiness Test:

Is this enough?

III.

The next thing that is clear is that people that answer yes struggle to understand people who answer no, and vice versa. This underlies a wide chunk of online discourse, where these groups essentially indirect each other non-stop.

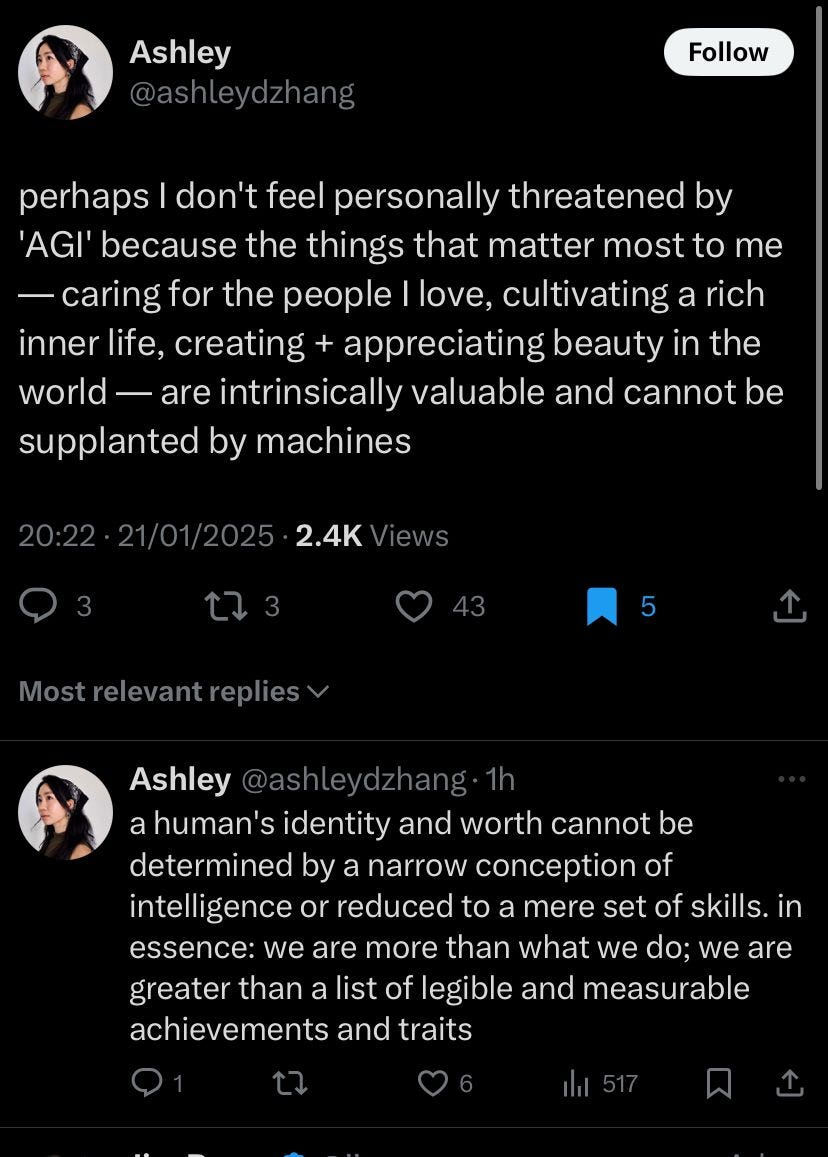

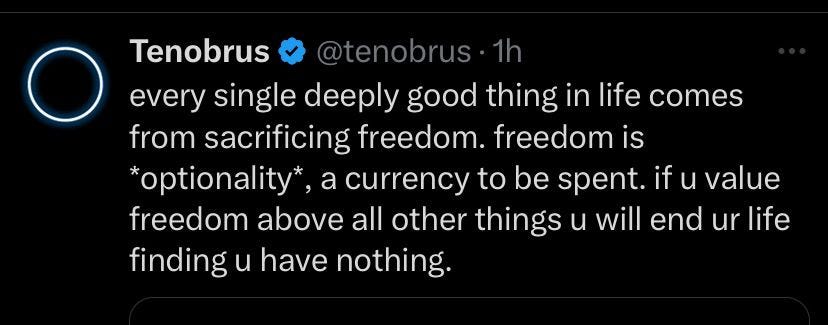

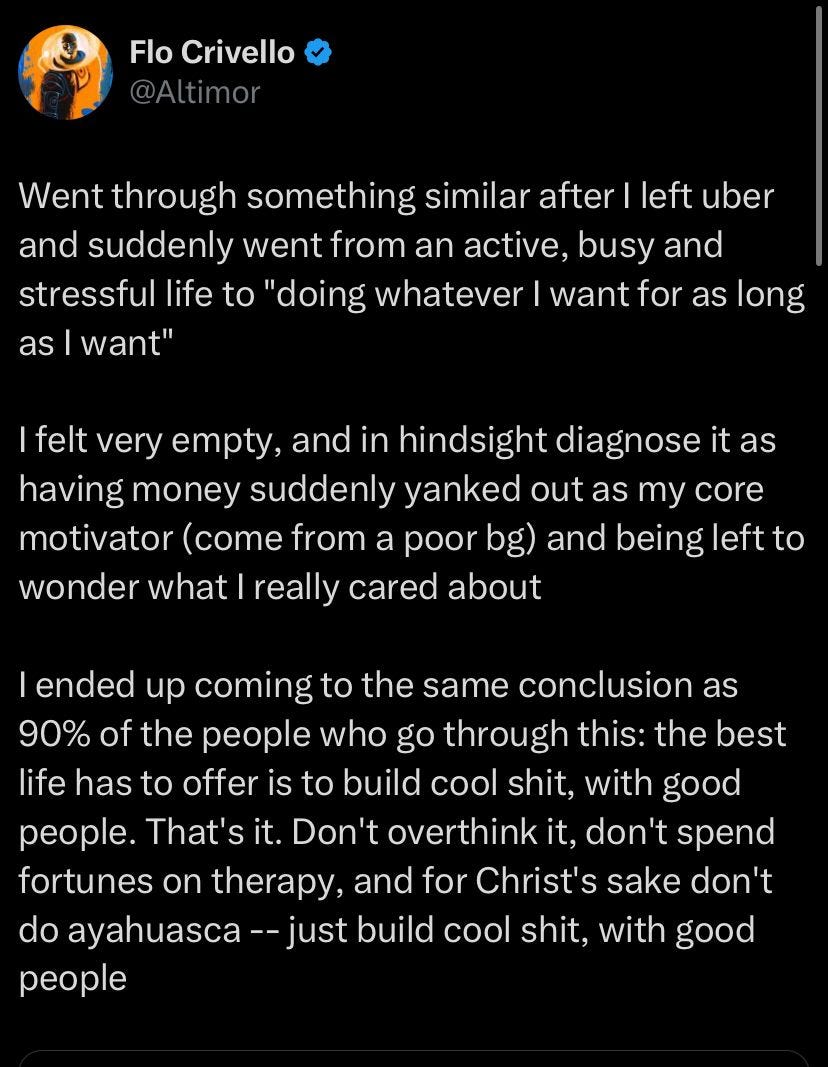

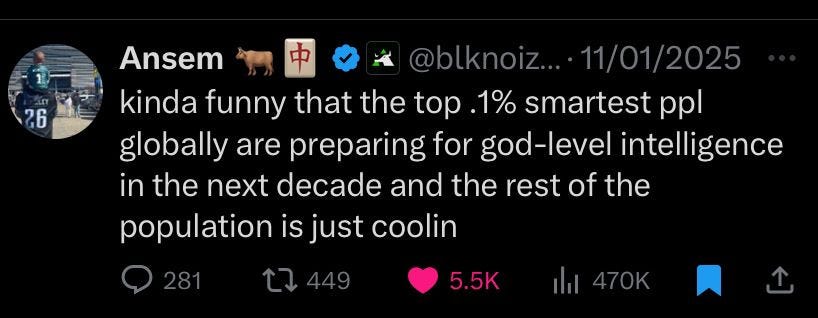

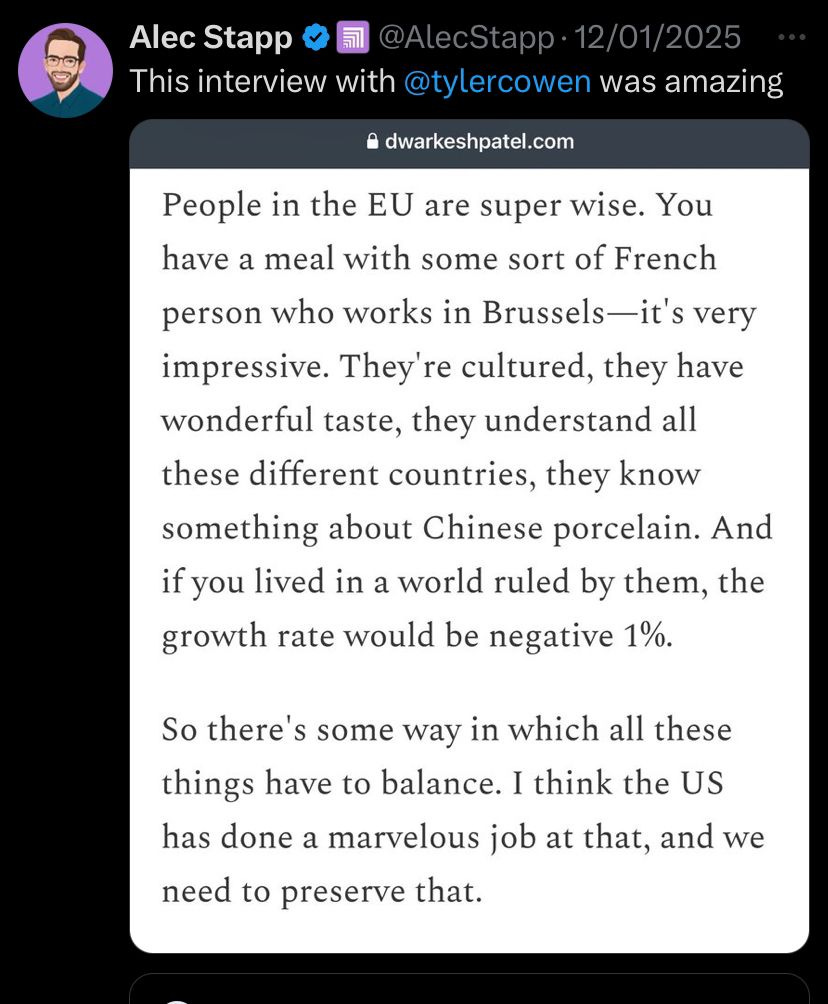

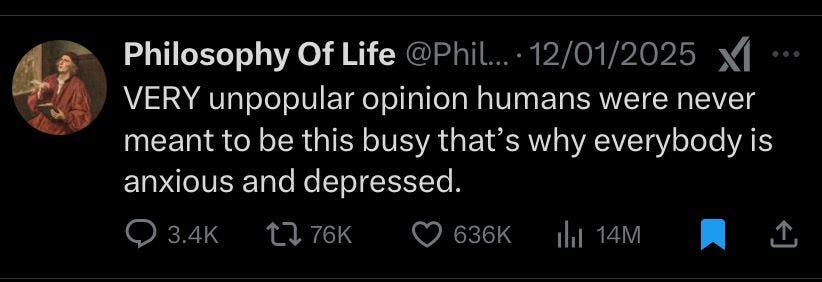

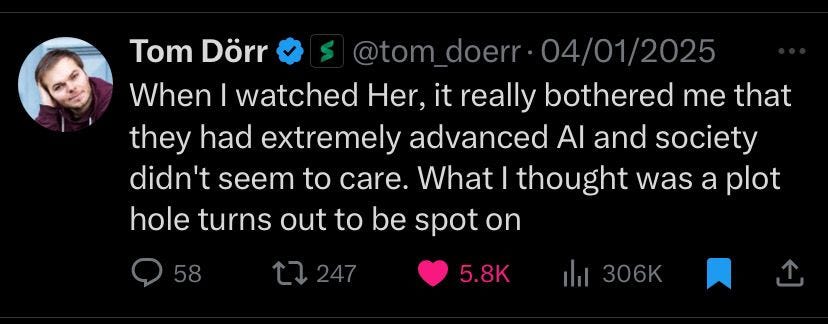

Some bookmarks from my feed in just the last couple of weeks, feel free to mark which group each person fits into as you go:

That last tweet is particularly telling. Because for all of the grey tribe preaching about agency and just doing things, I think it’s misinterpreted as a skill issue. It’s actually closer to a personality trait. And those people that don’t care about God-like AI? They mean it. And if/when it arrives, they probably still won’t care either. You could tell them now that AGI won’t ever happen and they genuinely wouldn’t mind. Same thing with respect to going to Mars. This is enough, which may in fact be preferable to nothing being enough ever.

IV.

The problem is that they are going to be forced to care, and we are running out of time to talk about this. Probably ran out already.

First, we have ‘Capital, AGI, and human ambition’ from No Set Gauge. Here’s my attempt at a tldr of their view:

There’s a potentially chilling long-term consequence of AGI: the creation of a permanently static society where existing power structures become immutable. Labour-replacing AI fundamentally changes the dynamics that have historically allowed human ambition to drive societal change. When AI can perfectly replicate any human talent and capital can trivially buy AI capabilities, the traditional paths for ambitious individuals to rise up and transform society disappear. Money becomes vastly more effective at achieving results, while human agency and talent become increasingly irrelevant. The result could be a neo-feudal system where pre-AGI wealth distributions become permanent, social mobility ends, and even democratic institutions lose their incentive to care about human welfare since human labour no longer matters.

The 9-5 and beach 2x a year might be enough forever, but society might not need to pay you for it for much longer.

Which leads onto Philosophy Bear’s argument in ‘We need to do something about AI now’. Tldr:

AI is already rapidly approaching the capability to replace workers across multiple job sectors, progressing far more quickly than skeptics predicted. This is obviously threatening massive economic displacement. When we automate fundamental cognitive capabilities, we create a permanent economic underclass by concentrating power in the hands of corporations and software owners. This isn't just about job replacement, but a fundamental restructuring of economic value, where entire categories of human intellectual and economic contribution could become obsolete at an alarming speed.

If capital is largely owned by the unsatisfied interesting people, and capital becomes the only form of power, then AGI locks happy people out of power forever, at the mercy of the neo-feudal system. If we don’t collectively organise UBI, they are in trouble.

Simultaneously, AGI takes over from ambitious people, because it can outperform them in every way. The people that need more must settle for what they have. If we don’t find something for them to work on, they are in trouble.

Scott Alexander suggests this might not be inevitable. Democratic governments could intervene to prevent extreme inequality, space colonisation could create new frontiers and opportunities, virtual worlds might provide alternate forms of fulfilment, and post-scarcity abundance could make traditional wealth inequality less relevant. His key point is that just because AGI breaks the current system of ambition and mobility doesn't mean we're doomed to stasis.

The game might change completely, but humans tend to invent new games. Just know that you may need to buy your ticket to keep playing very soon.

V.

This is broadly why I think the AGI X Human Wellbeing combination is set up to be complicated. First, most people are content and would be content at any point in human history. Second, some people aren’t really capable of being content and wouldn’t be content at any point in human history. And that second group is more likely to take AGI’s ability to its extremes in pursuit of their own extreme outcomes.

And it’s also why I think this is set up to be a new kind of culture war that’s already emerging under the surface of all those types of posts above. AGI’s arrival gets celebrated by a handful of people, and a handful of those people are probably going to end up with everything. Neither group understands each other ever again.

That is until the best case scenario emerges.

You know, something like Roon’s ‘Coherent Extrapolated Volition’ future:

In this universe we embark on a quixotic mission to solve godhood on paper and succeed. Mortal men comprehend infinity and have total absorb of the final mysteries of their own minds and of the universe.

How about that? Would that be enough for you?

I guess you’re going to find out either way.

I love this piece obviously, based on my glowing restack. I would add that some happy-go-lucky people who simply want contentment will be drawn -- are drawn-- to AI companions and are outsourcing simple family/community life to chatbots, snuggling up to the glow of their phone in a cozy dystopia.

I would say these people "won't care" in the sense that they are fat and happy cuddling with their virtual AI buddies.

The same people optimizing, producing, and stuck in the never ending rat race of everything never being enough are excited for AGI because they’ve lost touch with what makes us human. Their Utilitarian mindset makes them believe AGI is unquestionably going to happen (something i think is not possible, philosophically speaking) and they forget that the real thing that drives progress is some innately human, creative and indescribable phenomenon that isn’t replicated by 1s and 0s doing a bunch of if else evaluations.