AI Agents have a trust-value-complexity problem

screw it i'll do it myself

bit of a break from our regular programming but I’m thinking about UX again

0.

I’ve been reading Nick Bostrom’s Deep Utopia. It’s pleasantly weird, and not a bad introduction to the type of world many are converging on as our future i.e. perfect abundance.

He’s highly concerned with the interaction between human agency and AI agency. How do you feel good about yourself in a world where AI does everything for you?

To be more specific, individual agents would give each person tremendous personal capability, essentially making everyone super-intelligent by proxy. You'd have your own AI that knows your preferences intimately and can accomplish virtually anything on your behalf.

AI 2027 also marks agents starting to work as the thing that causes everything to get out of control. Although the authors are less focused on what agents will do for you or I, and more on what how they will help AI companies increase the pace.

Neither discusses the human side of interacting with an agent for the first time (and nor do they need to for what they are doing), but I’ve been thinking about it a lot.

Because agents are here, kind of. And no one cares.

Yes, this is partly due to the fact that they barely work. But I don’t think their effectiveness increasing will force their integration into the average user’s daily life.

As I think the other reason people don’t care is we don’t really have a way to think about them. Like yes, I can read Bostrom’s description of what my life will be like and think ‘yes, sign me up’, but the path there will be incremental. And taking the first step is hard.

AI companies are currently failing, in their comms and their UX, in getting people to take this first step.

So when Bostrom asks ‘how do you feel good about yourself in a world where AI does everything for you?’

I think a fair first question would be: how do we get people to let AI do everything for them?

I. What tasks can agents do?

When I think of any individual using intelligent agents to make their own life a personal (shallow?) utopia, I think there must be two categories of thing that the agents are doing:

Tasks that the person used to do themselves

Tasks that the person didn’t do themselves because they were either too time-scarce, energy-scare, or incapable on their own, or hadn’t even realised doing that thing would be a good idea until their agent explained it

In terms of how tasks in the first category vary, I think we have three dimensions:

Importance:

What are the consequences of the task being done (in)correctly and how much do they matter to you?

Complexity:

How hard is the task (for you), how much effort does it require?

Frequency:

Is this a one-off or do you do it all the time?

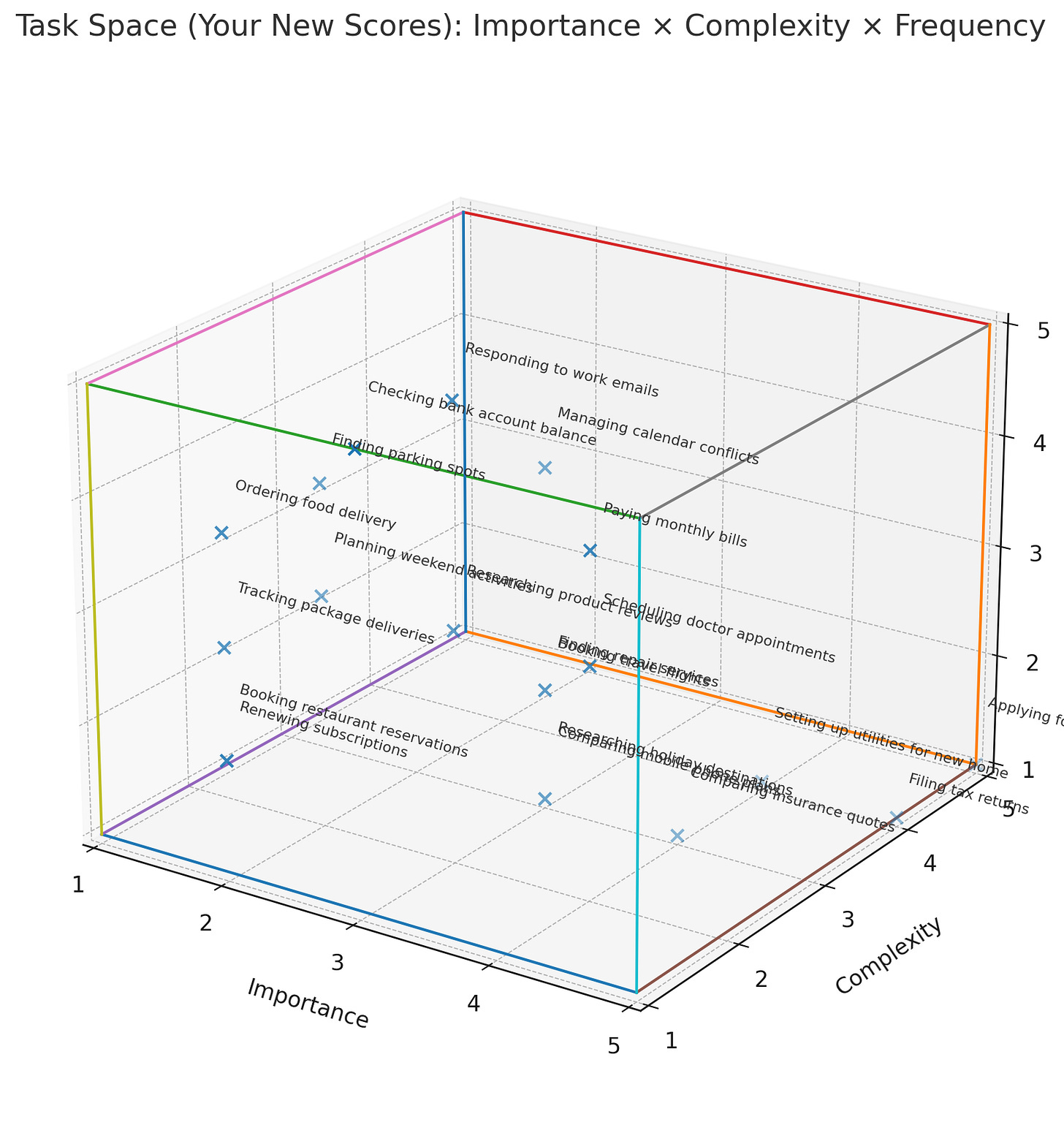

Here’s an ugly visual with some examples (Y axis is frequency):

In terms of making your life better, it seems clear that the best version of agents will do things that are high importance, high complexity and high frequency. Being high in just two is still really useful. In that list of tasks we have:

High Complexity + High Frequency: Annoying things that come up all the time but aren’t life or death, like managing calendar conflicts.

High Complexity + High Importance: Tasks you dread the effort of which you might also mess up, things like applying for loans/mortgages and filing tax returns.

High Frequency + High Importance: Stuff that’s easy but if you drop the ball you are hearing about it, like paying monthly bills.

And my basic point is: we are a long way from the average user being willing over to hand any of this over, even though this would be a huge change to the experience of modern life.

I watched the Google I/O show a few months ago, where they show someone wearing their AI glasses. They used an interaction where the person is walking around London, and their agent chirps up to tell them their colleague’s messaged asking to set up a meeting. They tell the agent to set it up, and it’s happy to oblige.

But when you’re watching, the only possible thing to think is ‘if that was me I’m definitely checking my phone to see if the agent set the meeting correctly’. Which means you’ve expended the same amount of time on the task anyway, if not more. And you look weird with your AI glasses on.

This isn’t good for anyone.

You can say that the paranoia will be sorted out by super-intelligence and the trust it will exude, and yes I probably agree. But I’m talking about the next few years of marginal improvement here.

So how do we get people to trust agents at all?

II. One small step for agents

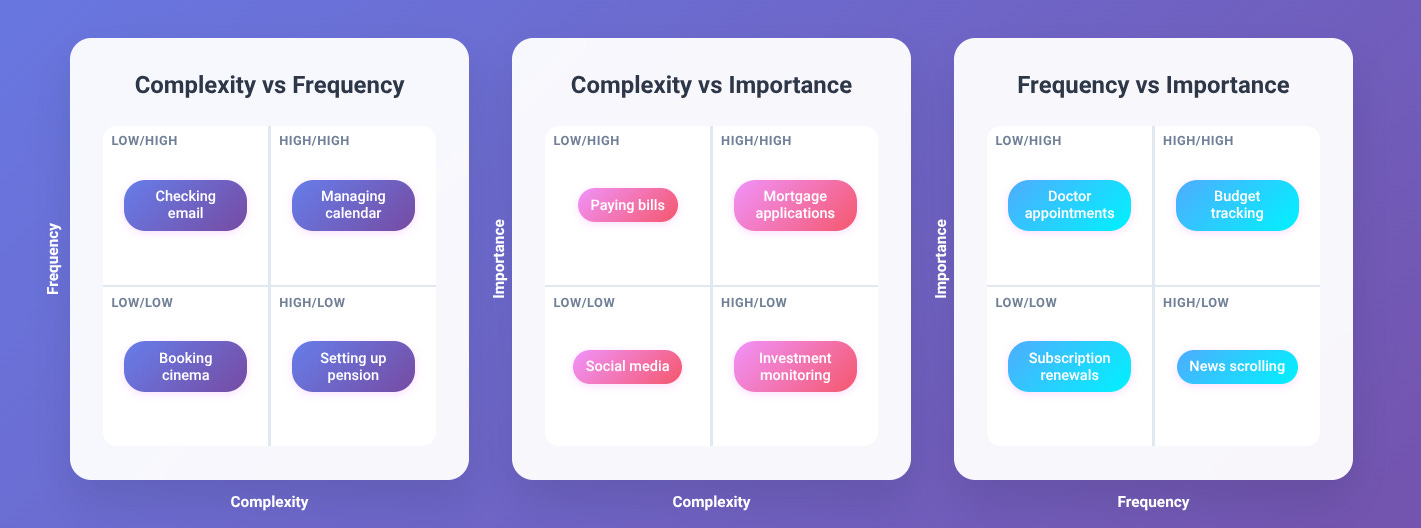

I had Claude split the three dimensions split into pairs, and put an example task in each quadrant:

The logical thing from a user psychology perspective would be to say:

‘We know users are going to be too hesitant to hand over the stuff in the top right quadrants. So we’ll start bottom left and work our way along those axes until we reach automated utopia.’

But the issue is that starting in the bottom left doesn’t work either, because the world is already a well-designed place.

Agent start-ups show off their tool’s ability to order a burger to your house, and follow that up with a claim that this is a big deal. But ordering a burger to my house is very easy for me anyway. So this adds no value.

Similarly, one of OpenAI’s big plays is to move into agentic shopping, as if online shopping hasn’t already been completely solved. Amazon can deliver anything I’ve ever dreamed of to my door tomorrow, and I can order it in 30 seconds. The agent can’t even do it faster than me. What is the point?

So, how do we get to the point of people handing over more complex and important tasks to agents?

From watching the major AI players attempting to communicate agents to the public: no one knows.

III. Does anyone know how to know this much?

I also said earlier that there must be two categories of thing that agents could be doing:

Tasks that people currently do themselves

Tasks that people don’t do themselves because they are either too time-scarce, energy-scare, or incapable on their own, or haven’t even realised doing that thing would be a good idea until their agent explained it

I haven’t seen any attempt at advertising compelling use cases of the second category.

Let’s say I spend 60 minutes a week looking at stats to help pick my fantasy football team. I then decide it’s not too tricky and an agent can probably do it for me. So I hand it over and gain 60 minutes back.

But if time, energy, and knowledge are not limitations the agent has, then this is a bad way to think about tasks. I’m treating the agent like a human when I shouldn’t.

If the agent really can effectively pick my fantasy team, then why not have it enter into every public league with a prize pool it can find, why not totally redesign my analysis strategy, why not have it gather the underlying data for every player on every one of my friend’s teams, and have it negotiate high-value trade deals with them?

You can apply this kind of thinking to lots of stuff, and suddenly you realise your life isn’t made of tasks. It’s made of goals and limitations. And it’s reallly hard to think about what you should try to achieve if some of your inputs are no longer limited.

I saw Jasmine Sun write recently that no one knows how to know this much, and I completely agree. Which is why it’s doubly useless for OpenAI to tell you its agent can book a train for you and save you 2 minutes. It should be 10xing you somewhere, somehow.

When working-agent-1 comes out, maybe your first prompt should be ‘ask me all about my life, work out things you can do to help me the most, and just do them’.

But in practical terms, what do we do?

From watching the major AI players attempting to communicate agents to the public: no one knows.

IV. Delegation is a psychological nightmare zone

But here we land at another reason why users might not let themselves be helped: people are really bad at letting others do things for them. Anything with any complexity in life comes with a ‘fine i’ll do it myself’ error code built in.

From ideation to completion, most tasks have the same failure modes. You can imagine these when weighing up handing over a task to a junior employee or to an agent (btw this equivalency is also why junior employees seem to no longer exist):

These are either the person failing to delegate:

“This thing is too complicated to explain” → easier to just do it yourself

“Writing out specific steps is too effortful” → easier to just do it yourself

“I’m going to get anxious about not seeing how it’s going” → easier to just do it yourself

Or the person delegating badly, which is very common in organisational psychology:

Poor understanding of the delegates skill/one’s own tacit knowledge → not enough context given → bad result

No clear description of what success would be → delegate forced to guess →bad result

On top of these, the number one reason people don’t like to delegate things they usually do themselves: inertia. You can either take the behavioural science approach of saying that’s a weird kink in human rationality and not expand any further, or you can take the psychoanalytic approach of suggesting people dislike change because it unconsciously highlights the infinite freedom of existence which is perfectly correlated with infinite terror. I don’t care which but it’s true either way. There will be a certain percentage of users who do not want to use AI agents because they are new and different and represent a chance for their lives to change in massive ways. This is understandably scary. These people will then come up with all the types of reasons for their inertia on the fly and to some extent will genuinely believe them, but you won’t need to take those reasons too seriously. Because once you solve those, they will freestyle something else in its place.

All of this is to say the utopia that agents will accelerate us towards will likely face some deceleration from the human side of the equation.

What do we do about that?

From watching the major AI players attempting to communicate agents to the public: no one knows.

V. Right back at you

I read this paper the other day: The philosophic turn for AI agents: replacing centralized digital rhetoric with decentralized truth-seeking

I still don’t really know that title means, but the paper makes a good point: the more complex life gets, the more we need help from technology, the more technology determines what you do.

Which means… less autonomy? This author thinks so, and it alarms him. It alarms Nick Bostrom too, hence his attempts to preserve human agency in Deep Utopia.

But this paper has an idea that I think is actually workable.

Instead of steering users toward specific choices, AI should help people find truth through open discussion and questioning, like Socrates. Who we did end up executing but let’s pretend there’s no weird ominous analogy to play with here.

This design would mean:

AI systems that ask thought-provoking questions rather than pushing specific answers

Helping users reach solid conclusions that hold up when challenged from different angles

Supporting people's own thinking rather than doing the thinking for them

Working like a good teacher who guides students to figure things out themselves

Which would take us way closer to existing at more useful parts of the axes from earlier. Or maybe it would help throw them out entirely. Because ‘human tasks’ are tiny in comparison to what’s actually possible.

For your life to become as good as possible, while you retain as much autonomy as possible (which you should, with all the free time you now have), you shouldn’t think about to-do lists at all. You need to take a step backward. Why are you getting up in the morning at all? What’s the goal?

Let your agent help you work that bit out, and it can take care of the rest.

Maybe then we’ll learn how to live with super-intelligence.

Re: AI and meetings. The value propn is in having the AI *attend* the meeting for you, make your points and build your alliances and understandings and get your decisions, and after the meeting, letting you know outcomes if they are surprising. That's what an agent does.

All of those micro-tasks in your diag and Claude's are pretty much automatable now. None of them really make sense in a fully AI-supported world.

(With picking fantasy football teams, using AI is defeating the purpose. It's entertainment, a test of YOUR skill and insight against others'. Using AI makes as much sense as using AI/robots to actually play the games and win Olympic medals.)

AI agents, if they live up to even a sixteenth of their billing, are a bigger change to How We Do Things than the transition from steam engines to electric motors for organising factories, and from gaslight to electric light in homes and on streets, and from messenger boys to telephones, and from horse and cart to diesel trucks and tractors. All put together. Possibly even bigger than the change from the miasma theory of disease to the germ theory, and the change from manuring to artificial fertiliser for crops.

Calendar conflicts and doctor appointments and payment reminders and tax returns and food ordering are going to be quaint historical practices that exist only in textbooks, like morris dancing, faxes, and running out of gas on the freeway.

Super interesting re: the psychology of tech and agency.

Two thoughts:

1. AI is currently the biggest FAFO experiment going.

2. Why bother with an AI guru question-asker when I can just read the OG Socrates?