How to learn about people in art galleries and smoking areas

both are a matter of life and death

warning: long

(thank you to everyone whose work I reference in this. most images are taken from the beautifully curated @0zmnds twitter account.)

"Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room.

So how should I presume?"I.

When you walk into the John Singer Sargent exhibition at the Tate Britain this spring, the first sentence you read on the wall is:

John Singer Sargent not only painted his sitters - he directed and styled them as well. He may have claimed that ‘I only paint what I see’, but what he saw was itself carefully constructed.

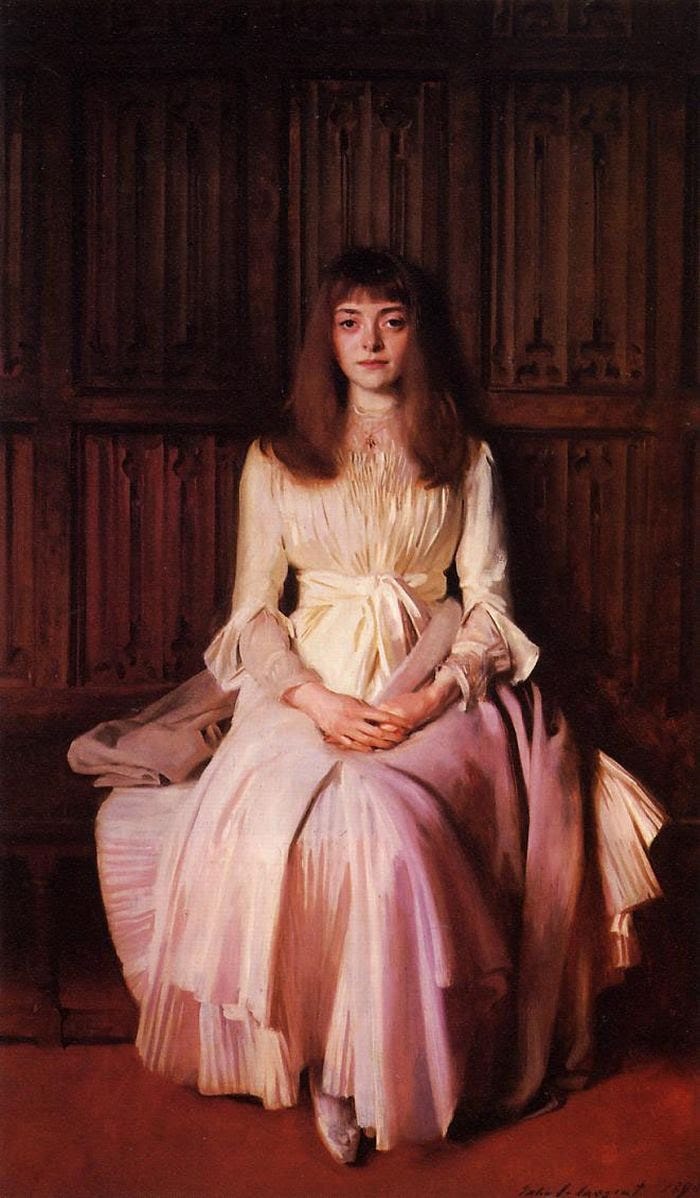

As I realise that I’m not quite sure what that means, the exhibition almost immediately peaks. Because the next corner you turn, you meet the gaze of the Portrait of Elsie Palmer staring back at you. Depending on how you deal with eye contact, it’s a pretty exciting/threatening view. To be honest, I’d never seen anything like it.

Much of the rest of the works on display had some diet version of that same effect. Regular scenes, with just enough irregularity to think something might be being said. Which leaves you kind of cognitively stuck for a second.

I struggle to explain why I like looking at paintings at the best of times. The best I can currently offer is that if you’re willing to go look at 1,000 paintings in your life, approximately 1% will move you. And those 10 (might) make the other 990 worth it. But even then I can’t explain why that is, so that’s not much for you either. Look, it’s something to do innit.

But as you can tell, I’ve never been educated on fine art. So when something does move me, I have to look elsewhere for some explanation of what’s going on. A bit like how luxury goods can only be advertised to people who don’t know what luxury is.

So I go searching for reviews when I get home from the Sargent exhibition that evening. My demographic information is what it is, so I end up on the Guardian. Which is where I’m met with …

Hello, hello. Dangerous territory for the ego here.

Being told something you thought was cool and interesting was, in fact, shit gives you a couple of options. War or peace. Conceding my map probably has a hole in it, let’s get a white flag ready and read on to see what it was that I missed.

First address of this critic’s issue:

This daring artist of modern life is turned into a stuffed shirt by a show that puts the dress before the face, the hat before the head and the crinoline before the soul in an obsessive, myopic argument. A painter with much to say to us becomes, here, a relic with no relevance.

OK. A few words there. I have no idea what any of them mean. I don’t think his paintings were altered in any way. How has the Tate Britain managed to destroy them? Again, must be my ignorance. Carry on, tell me what you mean.

Throughout this show, Sargent’s scintillating works are wretchedly displayed. There are clothes in glass cases everywhere obstructing sightlines, distracting from the art instead of illuminating it.

…

Instead of letting this fascinating portrait speak for itself, it is displayed next to a case containing a top hat, made in the late 19th century by Cooksey and Co of London, as the pedantic label explains.

Hmm. Weird to see art described as ‘scintillating’ and ‘fascinating’ in a 1-star review. But we’re reviewing the whole structure of the exhibition here, not just Sargent. I get it now. Now tell me why the hat in the case is a big problem.

It’s the way he paints that makes his art breathe. Yet here it’s hard to see that. The canvases are not only crowded by old clothes but shouted down by intrusive labelling and hideously set against ever-changing wall colours and lighting. Worst of all there, is no narrative logic. The display sacrifices any sense of Sargent’s life as an artist to its essayistic theme.

Wow I really am an amateur consumer of painting as it turns out. I didn’t even notice the rooms weren’t all painted the same colour (!).

Dad jokes aside, there’s something interesting here. Because this critic really means it. He clearly loves Sargent in general, but can only find anger in how the Tate Britain have presented him. Is he right?

You know what, here’s an admission: I also thought the props and their backstory were pointless. Me and the Guardian agree here. But that’s because of a general rule I already had going in: everything in an art gallery that is not art is pointless. It is not worth your time. If Sargent needed me to have context to appreciate The Portrait of Elsie Palmer, then he would’ve painted me some.

So this is where we diverge, because this critic isn’t just annoyed that the context is there and in the way. He’s annoyed it isn’t deep enough. He’s annoyed the story isn’t correct.

[Madame X] is just dropped in without any buildup or history (other than fashion history). We learn nothing about the Paris in which Sargent started his career: the capital of the avant garde where Manet and the impressionists were locked in artistic civil war with the conservative Salon.

Haven’t the Guardian also (pretended to have) read Against Interpretation? Sontag would tell them not to give a shit about the hats in glass cases. Or the people Sargent met in Paris. We’re talking form and experience here, not content. Don’t even bother reading the information plaques, bro.

However, that doesn’t fit as a satisfying takeaway either.

Because the plaques are there. And I saw everyone read them. And the Guardian gives a big shit about what’s written on them. So what’s going on?

Hypothetical: An alien arrives at your door tomorrow. Says they’ve been sent to find out what this thing humans have invented called ‘art’ is.

Easy. You show them some famous paintings. They look at them. They ask why those paintings are famous. You say because they are like so good. They ask what makes them so good. You panic and go to the Guardian art reviews section for backup.

You read that Sargent review aloud, and almost make it to the end, before the Alien demands you stop and explain this sentence specifically:

Worst of all there, is no narrative logic.

Asks what that has to do with painting. You try to remember.

Alien is growing impatient quick. You scramble to recall what art is about in the first place.

(Aliens speak in italics, btw)

“Well .. the whole point is .. eh .. exposing yourself to things. Shit you haven’t seen before .. that’ll make you think differently .. you know like .. transcendence .. meeting the unknown .. yeah that’s what I meant .. exposing yourself”

“And you expect the unknown to have narrative logic?"

“Yeah well I mean there needs to be some order to stuff .. you can’t just waltz into an exhibition and roam from painting to painting staring .. having no idea what you’re looking at”

“But you just told me the whole point was that you don’t know what you’re looking at!”

“Yeah but well some people do ok .. and that’s why you follow the right order .. that’s the way you learn whats going on .. maybe you just don’t have culture where you’re from but here its not just a fucking free for all”

“But who are these people? Why do they know the right narrative logic? They must have known the artist personally right?”

“Well no, I doubt it. They’re just experts.”

“Experts in what exactly? Where did they study? And their teachers, how were they experts?”

“How the divine fuck am I supposed to know that? You think it says that shit on the brochure?”

“Well it must have said it somewhere for you to be so confident about it! I mean, you let it guide your whole experience, don’t you? You walk in the entrance, you read the blurb on the wall, you look at the first thing, and you follow their order around to the end. Until the final line of the exhibition pushes you out the exit. Wow, some encounter with the unknown that is, mate. Not surprised you needed to read a Guardian review to tell you how to feel about it.”

“It’s really not that deep, you know. Stories just make things nicer. Every marketer in the world knows that”

“I’m just saying, you seemed to be all into art a minute ago. Now you’re telling me you need a sign to tell you how to look at it. You don’t even know who wrote it. You didn’t even think to ask! Sure, your motivation is to expose yourself to shit. But it seems more nuanced than that now. How should we put it, ‘I’m willing to encounter the unknown, just so long as some vague authority figure tells me I’m doing it right’?”

“I mean knowledge for its own sake is worth something, right? I can’t just throw myself into shit without being even a little bit prepped. You can’t act if you don’t know what you’re doing. If I see something I don’t understand, of course I want it explained. Hang on, isn’t that what you’re doing, by the way? Why do you want to know what art is? Too afraid to find out on your own?”

“Hmm. Wasn’t expecting you to pull a good point out of that. Let’s call it there.”

* Alien teleports back to home planet *

Is there a resolution in there somewhere? It’s hard to say. Every experience in society is guided somehow. But I’m still me, and you’re still you. So those interactions with the world are still different, no matter how guided they are.

Plus, the paths are designed by experts. Even if we don’t know them. It’s better than them not being designed at all, right? It’s good that we try to give things narrative logic, isn’t it?

I mean, wouldn’t something like wine collecting be less fun if you didn’t get to learn why some soil you’ll never feel matters for some reason you’ll never understand?

As I manage to bore even myself with that last question, I close the Guardian tab and move on with my life.

II.

It’s later that night and I’m out in East London. House white in my hand, and in my general disposition, I get talking to three guys in the smoking area. One mullet, one french crop, one bald. Feels like a set up to a joke. That’s going to turn out to be a correct prediction. I give you until the end of this section to guess the punchline.

Trev is the one with the mullet. Says he’s had a mental week in work and it’s great to blow off some steam. Says he didn’t log off until 8pm most days. I get the gist that he’s in marketing, and deadlines are stacking up. Trev says it’s worth it though. Gets to live in the liveliest city in the world. Get’s exposure to some big deal clients. Money’s not crazy, but enough to keep this up. High rents and a high cost per pint, but living paycheck to paycheck’s alright. Besides, is there another option?

Before he slides back through the bar to spend some time in a toilet cubicle, I ask him what it is he does at his company.

In an attempt at being as nonchalant as possible, he utters ..

‘Oh yeah, so I’m a Creative Director’

Down to three of us.

French crop is Leon. Leon says he doesn’t come out this way much. He’s spent the last few weekends more central. Apparently you just get a better vibe, and he’s met some cool people. Good drinks. Good music. No mental crowds. I don’t know how people even find out about these places nowadays, usually takes TikTok one week to guide the whole population there. Leon seems like someone with inside knowledge.

Tells me he’s actually heading there now. I’m half wishing for an invite. Doesn’t come.

As he leaves me with the last of their trio, I at least ask him to tell me what the spot is called.

‘Oh, it’s called Soho House’

Alfie must have lost all his hair by the time he was 25. Makes up for it with a strong beard though. As I decide not to tell him that, he makes a joke about Leon’s new obsession with his members club. “You know he’s glad you asked him that. I think he gets a dopamine hit every time he says the words Soho House”. I ask if he’s into that sort of thing. He says “that’s just for people who need social validation, real men don’t need that.”

Ooh, hello. Didn’t see that one coming. I ask why he thinks that.

Says he’s been reading a lot about modern society. Says men’s place is being undermined, and that they’re being taught to need other people to tell them how great they are. Which just results in conformity. Exactly what the system wants.

As I suddenly sober up, I decide it’s probably time to get out of here. But before I do, I ask where he’s been learning this stuff.

“Well, you have to pay to access it, but it’s called Hustler’s University.”

Now you may ask why these three guys are friends. They don’t seem to be that similar. They’re coding for some extremely different things. But they’ve actually got one massive thing in common, perhaps you have it in common with them too.

Let’s take a closer look at Trev the Creative Director first. What kind of person is he going to be, on average? Probably grew up nice, had time and space to express himself. Good at school overall, but thrived at Art and English. At some point, he starts to feel that neither artist nor writer is a sensible goal. I agree with him.

Still has that spark inside though, and is ready to work hard to let it shine through. Pays his dues for years at a couple of agencies, before finally someone recognises his ability. LinkedIn and Hinge updated. A new Creative Director is in town. He’s made it.

Then we had Leon. Let’s guess about him. Grew up in a smaller city, or maybe a big town. Always felt he was made for something more though, a realisation that happened to coincide with watching Entourage. So he moves to Hackney to join the cultural inside.

Only when he gets there, he just finds other people doing the same thing. And they all listen to artists he already knows. Turns out Urban Outfitters doesn’t stock anything different in London. He catches on that member’s clubs is where the real action happens. A work mate gets him into Soho House, and things are about to change. Private DJ sets, rooftop cocktails, hot people. And not anyone can just walk in. He’s made it.

Lastly, we had Andrew Tate sympathiser Alfie. This is the trickiest one to work out (incidentally, this is why every Manosphere video essay on Youtube is terrible). But I can make an attempt. He’s probably grown up with mixed messages on being a man. Old media says that’s the goal. New media says it’s not. The first thing he does to clear his head is to stop letting progressive types tell him what a man should be. But he still hasn’t got his own answer, so he looks elsewhere. Until, a very serious sounding, similarly bald guy appears on his TikTok one day.

And he keeps watching. Until he’s invited to the inner circle, where his man card is finally issued back to him. He’s made it.

Our joke is almost over. No, they still haven’t realised who it’s on.

III.

I can’t help but think about power a lot nowadays. Seems like every country in the world is going to the polls. Some are going to have some pretty extreme outcomes. Multiple wars on my phone. Maybe some more around the corner. Every big tech company is racing to be the one that changes human existence forever first. At the very least, before China. We’re kind of just watching and waiting.

Except, we aren’t. We’re all getting on with it. Trying to exact our own will onto the world anyway. Even if it’s on a minuscule scale by comparison. I guess that’s inspiring. So, what’s the driving force?

Nietzsche’s ‘God Is Dead’ is what philosophically kicked off the modern era, but to get there he laid out his building blocks. And the first of which is the cornerstone of his view of humanity: the will to power. A fundamental drive to asserting oneself over their environment. This would be, essentially, why we do anything.

But Nietzsche was compelled to write because things weren’t turning out like that. He wasn’t seeing a civilisation full of individuals clamouring for control over each other as if their life depended on it. He may have seen a minority doing that, but the majority were doing the exact opposite i.e. the emergence of nihilism. The will to power was still the starting point, but it became clear that for many, there was also a will to .. something else.

Given that those not interested in power were sticking around and not moving to another planet, some pretty basic calculus tells me that the total amount of power remaining in the world stayed the same. It’s just that those that had any interest in it suddenly got way more to play with. And they would have little interest in redistributing it.

Power is a loaded word though. To some modern traditions, it’s a dirty one. But it was a beautiful word to Nietzsche. Yes, powerful people do all the bad things. But they also do all the good things. And if you have no power? Then you don’t get the opportunity to do either one.

So Nietzsche was a fan of powerful people. Not because he supported people finding ways to dominate as much of the globe as they could. Because that’s not what he meant.

Nietzsche didn’t deal in definitions. He dealt in hammering the point home from 10 angles. And the point he tried to hammer home about the will to power was something along the lines of: ‘self-determination, the concept of actualizing one's will onto one's self or one's surroundings’.

So power isn’t control over others, it’s control over yourself. Over your own life. And you do it by ‘actualizing one’s will’, or in real people words, making a point of the fact that you are alive. By not hiding.

Working off this definition, suddenly a lot more people seem interested in power. Barely any of us want to be politicians, or CEOs. But we all climb a ladder, somewhere. Wealth, status, influence, knowledge, impact, artistry. They’re all paths that offer you the way to the life you want. That’s power.

Also, you get to measure success however you want. For some people, success is not having to set an alarm to wake up on time. That’s power too, even if no one knows you gained it.

Seemed like our three smoking area fellas had all made it in some shape or form.

Trev is now a Creative Director thanks to his grit and ambition. Leon is now a cultural insider because he never gave up in looking for the right places. Alfie is comfortable with his masculinity because he was brave enough to reject the mainstream messaging dragging him down.

I assume you see where this is going.

Trev has gained power in his career, but is stood there stressed and exhausted from overworking. Leon found his cool crowd, but he has to pay a yearly fee to hang out with them. And Alfie didn’t want anyone to tell him how to be a man, until someone even more masculine told him he could be his true manly self for £20 a month.

And they are all bragging about it. Why?

The answer can be ripped out of Guy Debord: it is because during the technological development of modern society (and mass media), when images of everything increased exponentially, at some point they took over from the real thing. Appearance became more important than reality. Map beats territory.

None of these three guys have gained any power. But they all gained a symbol that says they did. And that has enough value to trade over their real power in the process.

Trev has no freedom to choose when he gets up in the morning, or what he works on. The true artistic impulses within him have been snoozed indefinitely. He’s fundamentally exploited. But now he gets to tell his LinkedIn followers, and women in smoking areas, that he’s a Creative Director. He’s still brilliant at what he does, that’s why the company gave him the title. They’re just glad he’s barely making them pay for it.

Leon will never be sure where the rooms that make a city tick really are. But the goal was to be cool, and thus to be powerful, socially. That’s the story that he needs to keep selling. And now, he’s got the membership card to prove it. All it took was £3k a year. Soho House thanks him for it.

Alfie didn’t want anyone to tell him how men should be acting now that it’s 2024. And his solution, is to let someone tell him how to be a man in 2024. And he has to pay for it this time. Tate thanks him for it.

The punchline is that none of them see it like this. And that’s because the system has taught them to not look at it that way.

I mean, how come a guy that uses prostitutes to have sex doesn’t get to consider himself a stud, but a person that ends up with no control over their own life but has a fancy job title gets to consider themselves successful?

The answer is because that is how modern power designed it.

Byung Chul-Han’s most, and perhaps only, forgiveable book is Psychopolitics. It’s central thesis is that modern power is different from historical power in one key way: it is positive, not negative.

Negative power is authoritarian or Foucault-coded. Think violence, cruelty, policies, punishment. You get in line out of fear. Power is established with a whip, or the surveillance to ensure it never has to come out.

It’s been a long time since I’ve even been threatened with a whip, though. Which is to Han’s point. This doesn’t exist anymore. For you, anyway.

Positive power, on the other hand, is discipline achieved not through oppression, but seduction. Power that cosies up to the psyche, tells you exactly what you want to hear, and makes you think aligning your goals with the system’s goals was your idea.

This isn’t power exorcised with a whip. This is power exorcised with a pat on the back, and a ‘Good job, kid. I’m so proud of you’.

This feels good, makes you think you’re on the right track. Just, it’s a track designed by someone else. They also got to make the call on the end destination.

Which paints a picture not of a system retaining its power and preventing change by shutting people out, but of a system that achieves that by shutting people in.

This is a smart play, because when you think about it, negative power almost guarantees itself being overthrown in the long run. Those that get shut out and punished never lose sight of their enemy. They just need the right timing.

But positive power? It prevents the powerless from ever fighting their way out from being shut in. Because they don’t even realise they’re the powerless ones. They think they’re winning.

Whether that’s because they’ve got a fancy new job title, or because they have a new member’s card, or they feel like they’re being shown the inner secrets of the world, the all have one key thing in common: a vague authority figure to give them that honour, which they’ve been taught they can’t give themselves. They get told they are doing a good job. That they are becoming who they wanted to be.

But their excitement at getting a seat at the more premium table blinds them from asking the most obvious question in the world.

“Why were we allowed to do that?”

Or at the very least, if that gain of power was so meaningful then ..

“Why the hell was that so easy?”

IV.

We all know what it feels like to be indecisive, right?

I don’t mean on the micro level. Are we doing starters, do we get the 3 for 100 etc.

I mean the meso and macro level. Real life decisions. Potentially stress inducing. Usually taking the form of:

Option (a) - The surer bet i.e. “I’m pretty certain this is going to work out alright for me. At the very least, it can’t go disastrously wrong. And it’s also what other people would generally do, so no explaining myself to anyone afterwards.”

Option (b) - The less known i.e. “Something in me is telling me to go for it, but fuck knows what’s going to happen. Could be way better than (a). Could be way worse. And I don’t know anyone who’s done this. Neither does anyone I know. So I’m going to have to explain myself now, too.”

Seems strange that your brain is telling you two completely opposite things at the same time, no? Why can’t you just make a call?

Well, you may say the uncertainty over these things is because they both have genuine attractive properties. Or, given some more research time, you’ll shine some light on the unknowns of (b), then it’ll be obvious which way to go. So, eventually the pros and cons get weighed up. “There’s just a lot of things to consider right now, you know?”

Hmm. Yeah. I do know. And I also know it’s 2024, when you can get any information you want in about 20 seconds. Never mind the fact that no matter how many things there are to consider, I guarantee you have already considered them all. Yet you still take time to mull it over further.

No, most of the time these aren’t information problems. Especially if the information on outcome doesn’t exist until you actually pick one. Especially if you could make the choice for a friend in the same situation in approximately one second.

These are action problems. Where getting pulled in two directions at the same force creates a net movement of zero.

We all know what it feels like to be indecisive.

OK, so how can you want two opposite things at the same time? Surely evolution took care of that one. The homo sapiens that only cared about survival out-survived everyone else. And so we have basic motivations towards sustenance, sex, and the status that helps us get there. The feeling of happiness exists as a means to reinforce those behaviours, which is why that’s what you’re chasing.

But living as a human for approximately one day is enough to dispel that. As an easy proof, consider receiving this offer:

You continue living your life as it is from today.

or

Sam Altman plugs you into the NeuroMaximiser3000. Nutrients get pumped through a tube but taste like cheeseburgers and rainbows, you have a family with a virtual love of your life, and you get a Chateaux near Bordeaux. Once you enter, you never know it’s not real.

If you pick Sam, I honestly sort of respect it. But most people say they would rather carry on. Which means working out what people want out of life is more complicated.

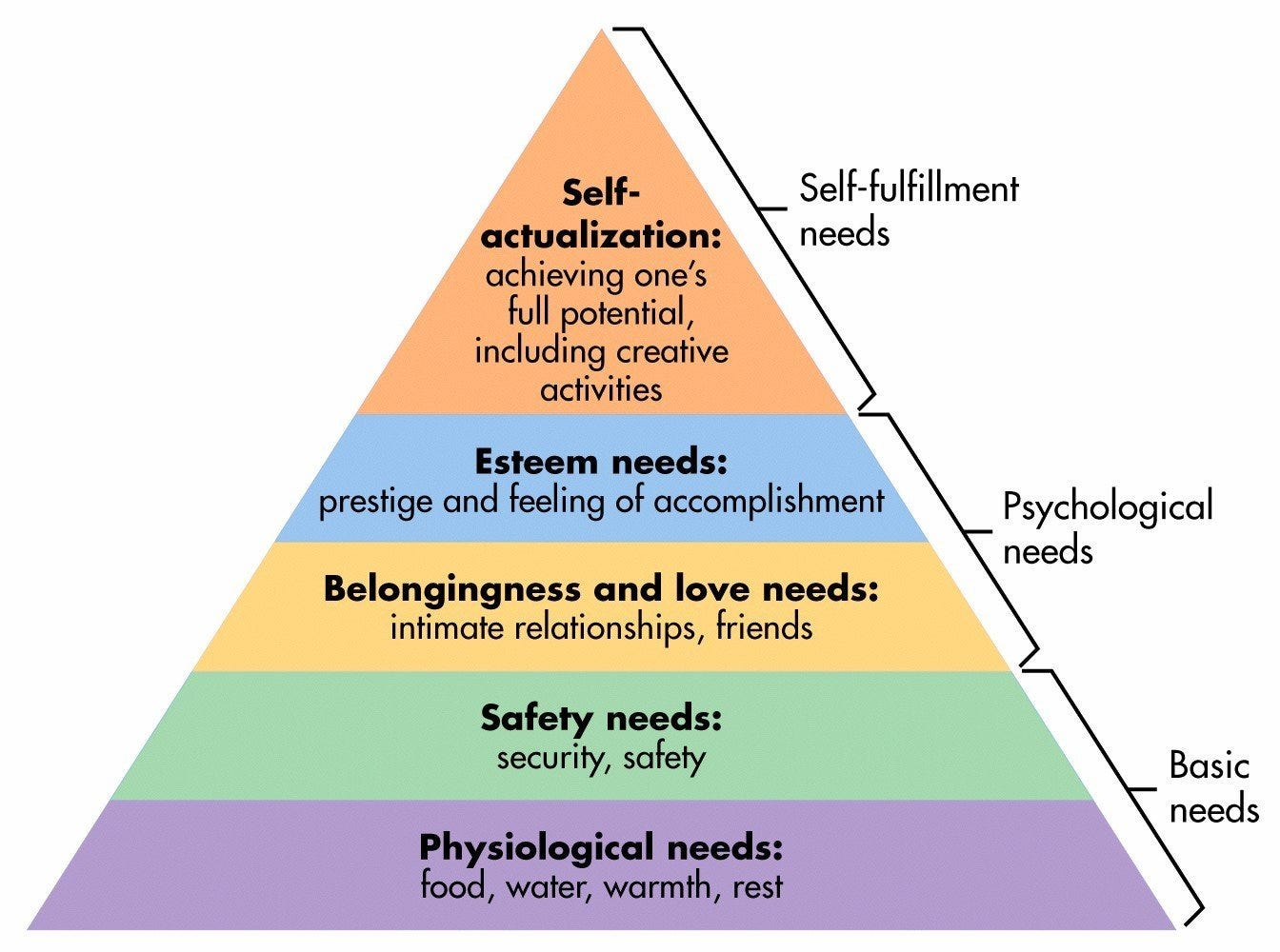

Hmm. Remember when you saw the hierarchy of needs for the first time in secondary school?

Your teacher probably pointed out how lucky who are to consider the bottom two rungs ticked off by default. Then invited you to think about the people in your life that count for rung three. Then they rushed to say that esteem doesn’t have to mean money or gold medals, and that accomplishment depends on your goals. Then once that is all sorted out, you will have a higher need driving you on, to self-actualise and be all you can be. Everyone agreed that this was inevitable, class ended, and we thanked Maslow for solving human motivation.

What that secondary school class robbed you of was something much more uncomfortable. Because Maslow’s work continued for years after that pyramid got out of control and became the thing that defined him. And his work just couldn’t get away from one problem.

Because as clear as the logic of the hierarchy is, it doesn’t seem to come with instructions. You know that episode of the Simpsons where Homer builds the barbecue pit, and is forced to cry ‘why doesn’t mine look like that’? That’s kind of what happened with Maslow.

In that, as much as he believed humans were naturally drawn to actualisation, achieving full self-expression and leaving their mark on their world, he had to explain how that lined up with the evidence. Because we were living in rich societies now. We don’t have to farm. Most of us don’t have to fight anyone. Being pretty healthy is pretty easy, all things considered. We’ve moved a long way toward utopia. So the scene has never been set better for everyone to make the move the top of the hierarchy, and self-actualise.

And Maslow’s problem? It didn’t seem like anyone did. More disconcertingly, it didn’t even seem like anyone was even trying. I guess the real Pyramids had weird puzzles guarding each deeper layer too.

That’s something that didn’t come up in secondary school. If only you would have thought to ask your fully grown adult teacher how it was they were self-actualising and really put them on the spot. Then the learning would have begun, for sure.

School ended and you went to college. Which is where, in many ways, you find out that civilisation has not necessarily been a complete success. You work out that ‘imagine all the people’ is cope and that humans are too complicated for that. They can’t always just do what’s right or what’s best for them, there’s bigger forces at play that screw up your equation to happiness.

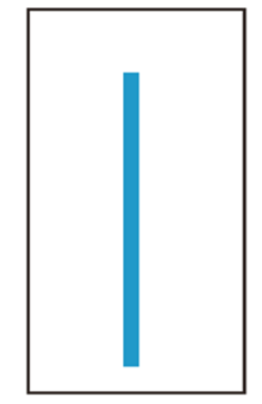

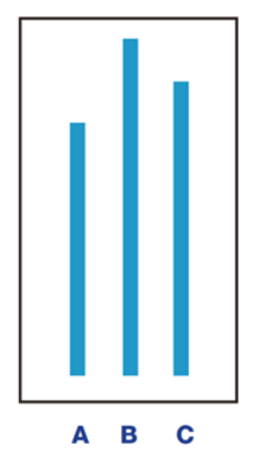

One of the first things you learn about there is Asch’s conformity experiments. As Professor’s engage their undergrads in some kind of gotcha moment, they show off his findings that even the most sensible people fall prey to group pressure in the most arbitrary of circumstances.

In Asch’s experiment a group of people get shown this:

Before getting asked which one of these they just saw:

The famous finding is that when everyone else in the group is a stooge that is told to intentionally give the wrong answer, you give the wrong answer too, knowing it’s wrong. Everyone watches the clips from one of the trials, sees the participants confusion turn to worry turn to acceptance, and everyone laughs at how conformist and weak we all are.

What’s strange, though, is that no one ever bothers to speak about the results in a full sentence:

“Over the 12 critical trials, about 75% of participants conformed at least once, and 25% of participants never conformed.”

Yes, 75% absolutely murders the 1% getting questions wrong in the control group. But what about the 25%? If the conclusion is that people tend to be strongly influenced by others in their environment, even when they know those people are incorrect, why are some people immune?

Firstly, if you’re fresh out of Research Methods and Stats I, you can relax. I know we can’t know what happened there. My point is: in any given social situation where one has to expose their views to the world, in-group survival is only one factor moulding your action, and sometimes, it doesn’t win. In this case, it didn’t win 12 times in a row.

Looks like Maslow wasn’t the only one with an incomplete theory of motivation.

People don’t realise that even Freud had a pretty basic outlook on humanity for the first chunk of his career. He thought motivation = pursuit of pleasure = avoidance of pain. His issue was that this couldn’t really explain *gestures to everything that was happening in 1900-1920s Europe*

He also wouldn’t have been able to explain you not wanting Sam Altman’s machine, or Asch’s 25%.

So in 1920, he publishes ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’, where he plays with two terms: eros and thanatos. He now claims these are the two drives underlying all human behaviour. And the reason there are two is because they want very, very different things.

Eros refers to the life drive, which encompasses instincts for survival, reproduction, and creativity.

Thanatos, on the other hand, is the death drive, which Freud posited as an instinct towards aggression, self-destruction, and a return to an inorganic state. Spooky stuff.

In terms of your own life experience, Eros is easy to accept. Think ‘damn it feels good to be alive’ and you’re pretty much there. Thanatos is harder to believe though. Doesn’t seem evolutionary, really. Wanting to destroy yourself, remove your own humanity. As a consequence of being in a shit situation, maybe. But a fundamental motivator? Feels wrong.

At the same time, it’s hard to get away from, as Adam Phillips found when he recently wrote ‘On Giving Up’. From his publisher’s summary:

From acclaimed psychoanalyst Adam Phillips, a meditation on what we must give up to feel more alive. To give up or not to give up? The question can feel inescapable but the answer is never simple.

Giving up our supposed vices is one thing; giving up on life itself is quite another. One form of self-sacrifice feels positive, something to admire and aspire to, while the other is profoundly unsettling, if not actively undesirable.

In trying to answer why people give up on some things, and pursue some things to their fullest extent, he stops by Beyond the Pleasure Principle in search of answers, where he comes out with this:

Freud described one version of what I am calling the wish to give up as the death instinct. Freud use psychoanalysis to ask: why are some people addicted to their own suffering?

…

The death instinct, I want to suggest, was Freud’s way of broaching the part of the self that wants, at its most extreme, less life rather than more life; the part of the self that wants to give up, to give up on, perpetually attempting and achieving a renewal of life.

So, it has nothing to do with dying. It has to do with how you choose to live.

Which means its rational basis becomes clear pretty quickly. Ironically enough, the death drive is the risk free strategy. You never truly try, so you never fail. You never stand out, so you’re never shunned either.

Conversely, the life drive is about imposing yourself. Not denying who you are. If you disagree with everyone else in the room, you tell them. You don’t give in. The issue is that when you’re not avoiding life then you’re not avoiding death either, and every climb just increases the damage of a potential drop.

As the best to ever do it once noted: “the advantage of laying on the floor, is that there is nowhere else to fall”.

Which takes us back to Maslow and his self-actualisation problem. When people were on the precipice of reaching his final level of human need and reach their full potential, he saw some people push themselves up, but a lot more weighed down.

Freud suggests this isn’t weird at all. Because this push-pull creates the core tension in the human psyche that has been the basis for, well, history. Both drivers exist, they just make the car work in different ways. Eros shifts the gears, by invention and revolution, and Thanatos keeps the wheel straight, by ensuring we keep enough inside to live peacefully together. But when you look across individuals, you can tell there’s differences in just how equally they share the driving. And that’s what Maslow noticed.

Because while his first big idea was that people wanted to reach their full potential, his second big idea was that there lived in people a fear of that very thing. This is his Jonah Complex, a tendency to shy away from your own capabilities and accomplishments due to fear of the responsibilities.

Or allow me to make it simpler: a fear of your own power.

Ayn Rand in 1971, on the Apollo 11 moon landing:

Harry Reasoner summed it up by saying simply, quietly, a little sadly, that if the moon is found to be made of green cheese, it will be a blow to science; but if it isn’t, it will be a blow to ‘those of us whose life is not so well organized.’ And this is the whole shabby secret: to some people, the sight of an achievement is a reproach, a reminder that their own lives are irrational and that there is no loophole, no escape from reason and reality.

So to sacrifice some nuance, I’m going to present to you two selves.

Self 1: Characterised by a cosmic lovechild of Nietzsche’s will to power, Freud’s Eros, and Maslow’s actualisation.

Self 2: Birthed by Thanatos, the Jonah Complex, and a Nietzschean will to be controlled.

The self that affirms life. And the self that denies it.

The self that pursues. And the self that gives up.

The self that wants power. And the self that’s scared of gaining it.

The question is not which self represents you. They’re both reading this.

The question is which one you are going to let dominate.

Well, come on, which one is it gonna be?

We all know what it feels like to be indecisive, right?

An immediate question is to what extent you get full ownership of over that choice at all. Because we don’t all live alone. When each us produces something with our lives, we produce it into the same system. Where you have a system you have power, and this system just so happens to care about what it is that you choose to produce. And it’ll be indifferent to what it has to submit to get that outcome.

In fact, the history of civilisation being a history of repression was a one-liner conceived by Freud himself, before it was co-opted by Herbert Marcuse. And Marcuse put it to work, trying to solve the question of what happens when you make societal and individual power face off with each other.

‘One Dimensional Man’ was the Frankfurt School’s starting quarterback’s most notable attempt at describing the shifting nature of power, as the 20th century saw technology and industry serving to dominate the masses into packing up their Eros and settling in for the status quo. He goes on to mercilessly exposes these mechanisms and their hidden nature, and the various ways they effectively caused critical thinking to vanish. He sought to work out if there was a way out, to a society that doesn’t suppress Eros. Something Freud thought was impossible.

I almost agree with his mission.

Because I think Marcuse does accurately diagnose domination, that’s what the dreary openers to this essay were about. I just don’t think he knows a submission kink when he sees one. 20th Century Man may be one-dimensional, but that doesn’t mean he’s impartial to hearing the words ‘Good Boy’ every now and then. Like, you ever find it interesting how even the most conventionally assertive, successful people still like getting choked in bed?

I’ll leave it to you to decide how much of that was a metaphor. But I know where we should look next.

V.

Nietzche used to say he could write in a sentence what others would need a book to say. Still unsure about that in his case, but one person that is true for is Kafka. Here is something you might have encountered on your travels:

Leopards break into the temple and guzzle the chalices empty; this happens repeatedly; eventually one can predict that it will happen again, and it becomes part of the ceremony.

That is the entirety of his parable ‘Leopards In The Temple’.

Post-game recap: The leopards want whatever sustenance is in those chalices. So they defy authority in order to get it. Eventually the authority stops trying to stop them. A new order is established. The plot is clear. But what’s the theme?

Let’s ask the internet what it’s about. (not cheating, these are the only actual attempts at explanation I could find on Google search).

Some blog about educational reform:

tldr: Leopards in the temple symbolise cultural change. Yeah they might have seemed scary when they were locked out, and yeah they may have forced their way in a bit. But now they’re here. And you know what? It’s OK. We can carry on with our ceremony, and they can join in.

And that’s how progress actually works in the real world. The new thing looks scary, but they don’t really mean harm. Maybe we don’t have to keep our things to just us. Thank you leopards, for showing us a new of way of looking at things!

In an out of character inspirational move, Kafka is pointing out that this is how revolutions happen: in increments, not in flashes.

It goes without saying that I disagree with all of these people.

They look at the leopards in the temple as an inspirational story of defiance and progress. They broke in, they are living it up, and now everyone else has to deal with it. The leopards break us out of the status quo and stick it to the system. A new system forms.

WRONG. WRONG. WRONG.

Here is the story again. Read closer this time.

Leopards break into the temple and guzzle the chalices empty; this happens

repeatedly; eventually one can predict that it will happen again, and it becomes part of the ceremony.

First question is: whose perspective is Kafka writing from? Like, for what is quite a violent act, why do they have such a calm tone of voice? They’re obviously not a leopard, but they know what’s going on.

So they must be on the human temple-keeper team, whose chalices are getting fucked with. Whose walls have been broken down.

Second questions is: Why are they so … chill about it?

Let’s change our frames of reference. Write from the leopard perspective. Take the classic Hero’s Journey structure that Kafka would hate.

Exposition: Leopards spend most of their lives dominating their environment.

Call to Adventure/Rising Tension: Humans arrive, start to make tools.

Crossing the Threshold: Leopards have to watch humans destroy their natural environment. Build huge structures. Hold all the resources. Take all of the power.

Approach and Ordeal: Now it’s time to fight back. Observe their ceremonies. Work out where the best entry for attack is. And strike.

Return: Leopards have moved up in the world. They used to have to hunt to survive. Now they’ve got the humans feeding them. And you know what’s really moving? That the humans have become more accepting along the way, too. Maybe we aren’t so different. Let’s live in peace together. Society is beautiful.

Now, that does seem to be story that everyone else read. I get it now.

Question though. If this is the leopard perspective, isn’t it weird that after all that time thinking they were fighting an enemy that ended up their friend, and all that evidence that human intelligence was enough to completely dominate their raw strength, isn’t it weird … that they just .. won?

Maybe the spoils of victory meant it wasn’t worth analysing exactly how they managed it, but if they wanted to, you know what might have been a valuable question to ask?

Something along the lines of …

“Why were we allowed to do that?”

Or at the very least …

“Why the hell was that so easy?”

eventually one can predict that it will happen again

Picture yourself as that cold narrator. You’re cowering on the gantry watching the first leopard break-in below. What’s on your mind?

Here’s one way it might go in your head:

“Hey those leopards are guzzling our chalices. We need to do something about this.”

But after one deep breath, you consider this alternative possible reaction:

“Hey, those incredibly dangerous animals we had to build a temple to keep out have found a way to break in. And all they want is .. what’s in these chalices?”

Now to us humans, we’ve gotten away (literally) unscathed. But to the leopards? The Hero’s Journey loop is closed. The audience is welling up. OneRepublic has started playing in the background. ‘Said no more counting dollars …’

The humans see how satisfied the leopards are. The sweating and twitching stops. They feign anger, before retreating to the back of the temple to confirm the plan. They walk back to the leopards to announce:

“Guys, we’re sorry we kept you out all this time. Next time, we’ll leave the door unlocked. Our house is your house too. So glad we can live in peace together.”

The world has turned a new leaf.

Except it hasn’t.

and it becomes part of the ceremony.

How you read those words tells you much more about yourself than you realise. Kafka was prescribing a method for incremental progress? Of course not.

The leopards in the temple are not a symbol of ‘How Change Happens’.

The leopards in the temple are a symbol of how change is prevented.

But you can see what’s so effective about that move on behalf of the person in power. It’s that the only characters in that ceremony who don’t understand what’s just happened … are the leopards. They’re too neck deep in chalice to even think about it.

They still don’t know who the joke is on.

Deliver it with me:

They’re no longer shut out of the temple, they’re ____ __.

VI.

Freud saw Eros and Thanatos as present in everyone, with both being necessary to a sustainable, rewarding existence. And thus, people who are satisfied with where they are in life are hitting them both in some form. And success tends to come with increased Eros.

But the genius of modern, positive power is that it hacks this algorithm. The conventional view is that people need to (i) deny themselves partly to keep them out of serious trouble and (ii) impart themselves on the Earth enough to reach their potential.

This isn’t strictly true. People don’t demand that both (i) and (ii) happen. They simply demand the belief that they are both happening.

And that’s why the prices of symbols of power keep inflating. Their demand is practically perfectly inelastic, if not worse than that. Consider that as access to free high-quality learning materials online increases a lot, the price of university also keeps increasing, yet the competition for places on courses only grows further. ‘Everyone already knows your paying for the piece of paper at the end’. I know you know that. I’m saying you’re going to send your future kids to college anyway.

Point is this: Leopards in the temple are fundamentally life-denying, but they think that they are fundamentally life-affirming. When Trev proudly tells his Hinge matches that he’s a Creative Director he means it. Their sense of autonomy is what guarantees their submission, and they’ll never have to face the true nature of their situation.

In chapter II in the smoking area, I picked three people you already don’t like in order to help get my point across. But this isn’t a necessary part of the deal. To make it clear that spotting these people isn’t as easy as catching their vibe, let’s seek out some other species of leopard. Ones that aren’t in your out-group. As of now, I see 4 categories.

Also, to show they can vary on other variables, we’re going to go from high effort to low effort. Or in other words, the ones that haven’t realised they’ve given up, to ones that are so close to getting it.

1.

Take a look at these 3 examples of what I am told qualify as news stories:

Or to generate a million more examples that may as well be real, just take the form: ‘Celebrity has flaw in character’ and ask ChatGPT to go crazy.

All three of the above became active discourses, and produced think-pieces where people mined for a conclusion of what this level of moral deception says about society and what we should do about it.

Here’s a conclusion: people do bad things sometimes.

And to the three authors of those articles, I ask the simplest of questions: what did you possibly expect?

I mean that so seriously. When Naomi Campbell says she cares about climate change one day, and works with fast fashion the next, why are you shocked? She is a brand, if she speaks you are getting marketed to, and you .. believed her? Do you also think the world is made out of cotton candy?

And a second question, when you spot the flaw and publicise it, why do you think .. this is achieving .. anything?

If Andrew Huberman has a successful health podcast, but is unfaithful to women in his private life, and this exposé loses him listeners, and those listeners lose their health advice .. is that a good thing?

The obvious take is taking someone down makes you feel powerful yourself, but there’s something else going on here.

We’ve gone through enough by now to say this: the system is smart, and positive power thrives off you thinking you’re getting somewhere. So consider this possibility, unpalatable but fair, that the only acts of rebellion you engage in are precisely the acts of rebellion the system allows you to have.

(As an example, do you not think it’s weird that a rebellious punk band like Idles, singing about how much they hate their own government and are demanding change, are consistently on stage at the biggest festival in the UK to a worldwide audience? Let me guess, the rebellion only kicks into gear around the 6th album?)

But one thing I can’t help but think is that tearing down celebrities from their pedestal only reinforces one thing: that the pedestal is the default.

Similarly, going out of your way to criticise the contents of advertisements, really only emphasises that you think the contents of advertisements are important. For some reason.

(I’m not saying advertisements aren’t influential, I’m saying the fact that they are influential indicates a society of people that gave up)

Believing that the character of famous people matters, or should require a higher standard of person than you, is a belief that powerful people are different. And that a life where you don’t pay attention to them somehow matters less. It’s a belief in authority figures.

Scratch that.

It’s a need for authority figures, disguised as an act of rebellion.

It’s life-denial, disguised as life-affirmation.

From the banned-book list:

Universities protect the status quo by letting you protest the status quo. Go ahead and organize a march there, the police will helpfully block off the roads so you can get a video of you screaming at them for blocking off the roads. Frantic energy as a defense against impotence, what could be more American?

2.

Moving on from people who think they are changing the world for the better, we have people thinking they are changing themselves for the better. Specifically, within a large company.

For the best way of thinking about this, I recommend all of Zvi’s Immoral Maze essays. But I will attempt to explain it concisely here.

Picture this: you're a bright-eyed, bushy-tailed new hire at some big shot company. You're thinking, "I'm gonna crush it here, rise to the top, make a real difference." But then you start to notice some weird shit.

Turns out, the people who get ahead in this place aren't necessarily the most skilled or hardest working. Nah, they're the ones who are best at playing the game. It's not about creating value or doing good work. It's about schmoozing the right people, covering your ass, and making sure you're not the one left holding the bag when shit hits the fan.

Zvi breaks it down like this: in an immoral maze, the path to success is paved with deception and branding. It’s not that quality of work doesn’t matter, it’s just that the appearance of it matters way more.

And here's the thing: once you're in the maze, it's near impossible to get out. Because the skills you need to survive and thrive in that environment, they're not the same skills that serve you well in the outside world. And guess which ones you just spent years sharpening?

And this is the, somewhat extreme, kicker:

Being in a maze is not worth it. They couldn't pay you enough. Even if they could, they definitely don't. If you end up CEO, you still lose.

You think you’re making it. You’re ruining your chances of ever being free again.

3.

‘Knowledge is power’

There’s a thing people say. And it seems pretty logical.

When psychotherapy began as a concept, the various different troubles people needed help with could be abstracted to one notion: they were stuck.

Stuck on something. Stuck in something. Stuck with something. That was causing them pain.

And they wanted to become unstuck.

Becoming unstuck requires movement. Requires action. But this action needs to be informed, to make sure it’s in the right direction. It needs understanding of exactly what is going on in that person. It needs knowledge.

The problem happens when the system learns it can use this to its advantage too.

Knowledge is power? Here, have unlimited knowledge. Don’t worry, the unlimited power is coming. Just so long as the knowledge gaining ends, so the action can start, and the power can come rolling in. Oh wait, what does infinite mean again? Postpone the revolution, 5 new papers on the theory of how to start a revolution just dropped.

The Last Psychiatrist:

Your thesis is that the system is oppressive, and that’s what you’re fighting against. Then why was your interest in destroying it legitimised - encouraged? Why was there a major in college that allowed you to destroy patriarchy? Or did you think the university was a safe space outside of that system from which to critique it, for 50k a year?

(yes, I understand the meta-irony of this essay existing here. no, I won’t be dwelling on it).

I accept this is the point of the essay where I am at highest risk of being misconstrued. I’m not dunking on these people. They’re probably more useful than me.

The point is this: I’m sure Elon Musk is mildly annoyed that college humanities departments think he’s an oppressor. It’s just that he’d much rather them be there than in boardrooms. Or at the very least, spending an hour a week on LeetCode.

Or as TLP had it:

“I learned how things really work.” Did you learn that they can work without you?

Knowledge is only useful if it informs action. If there is no action, and just more knowledge, then positive power is at work. On you. It’s all good knowing what needs to be done. The submission occurs when you think that’s a success in itself.

And in terms of the total fetishisation of knowledge over pursuing true power, this is pretty much says all that needs to be said:

Here’s a rule: if you ever hear someone explain an idea or argument for something using words or a tone of voice they wouldn’t use in regular conversation, then that is not their idea or argument. They got it from somewhere else, and thus can only replicate it in the form they received it in. Which means you’re talking to someone else. And the person opposite you is hiding. But they’ve convinced themselves that’s not the case.

Knowledge is power is a thing people say. Probably wrong. Probably dangerously wrong. Because in 2024, knowledge is the thing you’re using to prevent you ever actually acting. And thus, from ever actually getting power. And by power I mean controlling your own life. Becoming unstuck.

And, by the way, if you choose to fully maximise knowledge of things in order to truly guarantee you will never change anything, then you are what we call an ‘academic’.

4.

Downstream of active knowledge champions are the passive knowledge champions. The ones so smart they think inaction is logical.

Over a decade ago, when using the word hipster earned clicks, the NYT published ‘How to live without irony’. It contains a strong description of the modus operandi of those that do live with irony. It paints a picture of a character you might recognise.

Essentially, ironic living is portrayed as a self-defensive mode of dealing with the world. Stemming from generational disillusionment and over-reliance on digital technology, it allows an avoidance of risk and responsibility through detached, insincere engagement.

At the time that article was written, irony was characterized by:

Nostalgia for times not personally experienced, appropriating outmoded fashions, mechanisms, and hobbies.

Functioning as a self-defensive shield against criticism by pre-emptively acknowledging its own failure to be meaningful.

Allowing people to dodge responsibility for their aesthetic and other choices.

Stemming from the belief that everything has already been done and serious commitment to beliefs will eventually be made laughable.

That was 2012 and about Millenials. Let me show you what I think the 2024 Gen Z version is:

Meme pages about middle class young people, making fun of middle class young people, followed exclusively by those people. Like, the literal group doing those things.

Being able to laugh at yourself is great but .. what if your identity is the joke? is the meme?

If you can only do/wear/care about something as long as you can do it with a hint of irony, and with a nod to the meta-game you’re playing by doing it, you’re playing a submissive role on purpose. Because you then can’t exist outside of that mini-universe.

Like, if you’re scared of loudly saying you like something, that means you’re scared of being you. You’re scared of imposing yourself. You’re scared of your own potential.

This may be a cultural response to being given no clear future as a generation but unfortunately, understanding how the system is screwing you, and refusing to take yourself seriously as a result, isn’t a form of empowering yourself.

You can still say you vaguely want things to get better for people and have it be true. You’re just waiting for someone else to do it. In terms of your ability to become someone who can affect the world, you are utterly giving up.

VII.

That last case study should draw an obvious question. If living ironically is a version of a complete submission to powerlessness, what does the opposite look like? More directly, what do people not afraid of their own power look like?

Well, the opposite of being ironic is being serious, so let’s start there. You’ve probably met a lot of people you consider serious in your life. You probably wouldn’t opt to spend time with them unless you’re being paid to.

That’s fair, but I invite you to change your definition, and get in line with the version in Visakan Veerasamy’s ‘Are You Serious?’

Here’s the key point:

Good books are written by serious authors, and being deeply immersed in their work stirred something in me that made me yearn to live a serious life myself. It just seemed so obvious to me that a serious life is a life well-lived, and it’s always been weird to me how uncommon this perspective really is.

As I got older it became clearer to me that not many people are really serious about anything. Some people go their whole lives without ever having met anyone else who I might describe as actually serious, so they find it hard to believe that anybody could really mean what they say, since everything everyone says is bullshit. I remember feeling like that myself at some of my low points in life, when I was at my most depressed.

Looking back now I don’t think I was entirely wrong, the issue was that I was overly fixated on unpleasant truths. I find myself compelled to describe it as “LinkedIn World”, where everyone is performing a bullshit role in a bullshit play. And my blessing was that I did still have a little light in the darkness from the authors I mentioned earlier, which felt like a glimmer of honest earnestness. And that glimmer has kept me going through everything.

And two examples of people who found something to be serious about:

Justo Gallego Martínez was serious. At about 36 years old, he got stricken with tuberculosis, got better, promised God that he would build a cathedral, and spent the remaining 60 years of his life building it. "When I started building, word on the street was that I was crazy. They didn't believe I would be so dedicated... I'm proving them wrong."

Hokusai was serious. Here’s him talking about his paintings after ~70 years of working on them: “From the age of six, I had a passion for copying the form of things and since the age of fifty I have published many drawings, yet of all I drew by my seventieth year there is nothing worth taking into account. At seventy-three years I partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants. And so, at eighty-six I shall progress further; at ninety I shall even further penetrate their secret meaning, and by one hundred I shall perhaps truly have reached the level of the marvellous and divine. When I am one hundred and ten, each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.”

Obviously, building cathedrals or painting waves aren’t inherently serious endeavours. The point is how they went about it.

It’s a method of living you tend to see in every top level athlete, entrepreneur, artist, scientist and revolutionary. Everyone that makes an impact. You know when you see people talking about how much ‘aura’ people have nowadays? If they have more than you, they’re more serious than you, and thus more powerful. No exceptions.

They saw something in themselves, and they tried to maximise it. They did maximise it. They couldn’t have imagined doing anything else. There was no scoring system to say how well they were doing it. There was no expectation that they would even pull it off. There was barely even anyone looking. They spend their life on it anyway.

And that’s how you know they were serious about it.

The let the life-affirming self dominate. They weren’t afraid of themselves.

If you really want to know how the world works: they became powerful because they were powerful already.

or what would have saved me many words:

We’re about 95% through this essay. And we’ve lost about 95% of readers by now. So it’s time I can tell you straight what the point is without feeling like I’m exposing myself too much: this difference between being life-affirming and being life-denying is the single most important psychological decision you will make in your life.

Everything you hope to come out of 80ish years of existence comes down to that at some fundamental level. Disagree with it now but I guarantee that years later, when the story of who you are falls apart, when the drugs don’t work anymore, when the awkward silence falls at your family dinner, and you think there’s gotta be something more and look to someone else to save you, you’ll know that I was right. That doesn’t mean that you’ll regret your decision. It’s just that if you do, it will be too late.

Here’s the deal: no one’s asking you to change the world. The point is that you could at least try. And you don’t need someone to ask you. But you do need to do it much, much differently to how people currently think changing the world works. The truth is that you don’t have to waste time defining yourself and your ideals in advance. You just focus on action, and the self gets built along the way, but only in the service of trying to build something more. And then you learn that that’s what power was all along, and is in fact the only kind of power you can have ever truly have. The power to change yourself. And listen, if you can’t even manage that, then I wouldn’t worry much about changing the world anyway.

But if you just don’t see the point in that, I can’t blame you. Leopards in the temple still get to think they are the real rebels after all. Plus, they get the comforts of what was in the chalices, and didn’t even have to face any real danger to achieve that. They even get a story to explain what it is they did that makes them look pretty cool. Which means others see them as that too. Even if you sometimes wonder if it was all futile, if it even counts as real, we all end up in the same place anyway. You could have the internal breakdown over dinner, but 1000% of the time your brain will repress you back to normalcy before you sit down at the table again the next day. Yes, things could have been different, but did you really need to see exactly how?

You know what I’m going to say. When I hypothetically asked you if you wanted real life or Sam Altman’s happiness machine, you said you wanted the risk and uncertainty of the real thing.

And now it really should be obvious.

That everyone is actually faced with that choice everyday. And you can tell what option they went for. When you watch them in art galleries. While you chat to them in smoking areas.

The choice is yours, too. You just don’t think about it.

The thing is, though, the less time you spend thinking about it, the more the world is choosing for you. And all it ever took was a pat on the back. Or a chalice in a temple.

Good thing knowledge is power, right?

Hope you had a good summer everyone.

Your time is running out.

You the best! Your writing inspires & provokes.

Incredible. So good. You’re quickly becoming my favourite author on this site