Romance often occurs at unsolved equilibria

get it while it's hot

I.

You know when you read an old mystery novel, the type where the protagonist is chasing/being chased by someone across Europe in like 1930, and they have to use all manner of trains, boats and dodgy documentation to cross the continent, and you think to yourself “damn, things really used to be so much more inconvenient, but also, in a way, so much … cooler”?

I think it might mean that there’s an amount of uncertainty required to truly feel alive. Eros in quite a pure sense.

There’s a certain kind of discourse pattern that happens where Player 1 starts the game by saying “sigh things used to be so much better in the past” and Player 2 shoots in with something like “um actually if you went there now you’d hate it because you wouldn’t have this thing you currently like and also you’d die immediately”. I think that riposte often misses the point.

Yes, sure, everything measurable gets better all the time through history, but the best part of a story is never the ending. Not even the happy ones.

If you could click your fingers and shoot 10 years into the future to where your life will certainly be more comfortable and free, would you do it? I doubt it.

What is sex without flirting? What is romance without the tension it’s built out of?

II.

In The Colors of Her Coat, Scott Alexander reflects on how the pursuit of art has changed. In medieval times, the perfect ultramarine blue pigment used in paintings required an incredibly dangerous and expensive journey to Afghanistan, complex extraction processes, and was so precious it was reserved almost exclusively for painting the Virgin Mary's robes. When peasants saw this perfect blue in church, it created genuine awe and spiritual connection. Today, we can recreate that exact blue synthetically and cheaply, but we've lost the wonder.

This followed Erik Hoel’s warning of ‘semantic apocalypse’ i.e. how technological abundance cheapens our appreciation of previously rare and meaningful things. Hoel argues AI is doing this at mass scale: flooding culture with "close-enough" imitations that don't need to be perfect copies to drain the originals of their specialness.

Scott takes it beyond art, to a type of hedonic adaptation undermining everything meaningful. As AI advances, it may solve poverty, cure diseases, and fulfil human needs so completely that we lose all sense of purpose and wonder. We'll have everything we ever wanted and be bored by all of it.

It makes me think of travelling across Europe.

If I want to go to, say, Ljubljana, I can book a flight for tomorrow in less than 60 seconds without moving. I don’t have to convert currency. I don’t even need cash. I don’t need to learn any Slovenian. I can get to my plane seat without saying a word. I can navigate straight to my Airbnb. I can route myself through all Top 5 attractions in an afternoon.

And as I stand and stare up at Ljubljana Castle, or whatever, it just cannot be awe nor wonder that I’m filled with.

Truly a remarkable achievement that it was all made possible in just a matter of decades, but God doesn’t it all feel so unromantic?

In what was actually quite a hopeful essay in the end, Scott concluded:

Something bothers me about the whole semantic apocalypse framing. It focuses too much on the social level, denies personal agency. Yes, we as a culture are post- some semantic apocalypse where listening to the great symphonies of the past has become so easy that we never do it.

…

G.K. Chesterton wrote lots of stuff about how if you were really holy and paying attention, then the thousandth sunset would be just as beautiful as the first.

…

Chesterton’s answer to the semantic apocalypse is to will yourself out of it. If you can’t enjoy My Neighbor Totoro after seeing too many Ghiblified photos, that’s a skill issue. Keep watching sunsets until each one becomes as beautiful as the first.

I can’t deny there are moments in life where you realise how beautiful the thing that’s been right in front of you the whole time actually is. You can use psychedelics to force that very process.

But it’s hard to turn that feeling of euphoria and being intertwined with the universe into some kind of daily ritual. And people tend to up dosages over time for a reason.

Instead, I actually wonder if there’s only a certain amount of joy to be derived from games that are solved already. I obviously don’t mean dopamine-coded hackable joy. I mean romantic, sexy joy. I mean magic. I mean the memories that actually make you smile still now.

Even in the 1970’s, travelling through Europe must have been a massive pain. Different currencies in every country, cash only. EU citizenship wasn’t a thing and you can’t Google how the individual visas work. Pocket phrasebooks but you still don’t know how to actually pronounce anything, and speaking very slowly in English doesn’t help either. Is that train pulling into the station the one you’re supposed to be on? Who knows, let’s get on.

If I say to you that’s so much cooler than my trip to Ljubljana, and I’d much rather read a story of someone doing that than one set in 2025, are you going to tell me my view is rose-tinted?

When you see Google demoing those glasses that automatically translate what the person across from you speaking a foreign language is saying, are you glad we solved that problem?

The thing is that I sort of am. That’s undeniably progress, and of course opens up a path to something wilder than just seeing what another country is like. But the sense of adventure is robbed. There is zero uncertainty.

And zero uncertainty is a pretty bad deal in life. It’s TikTok. It’s fast food. It’s satisfying. But you know it’s slowly killing you. And if you want everything to stay under control then you may as well sign up for Wireheading early access. You kind of already have.

Yes, I do suppose it’s possible that you can bring yourself to feel awe when seeing a work of art for the 100th vs 1st time, but I struggle to shake that the 1st and 100th viewings are fundamentally different experiences.

III.

The reason wireheading doesn’t appeal is because happiness clearly isn’t the point of living. Living is the point of living. The real wish is to go on an adventure. Even the most narcissistic of us at least want a story about themselves to be able to tell people.

And you cannot go on adventure within a solved game. Because you’re risking nothing, you know the ending already. It won’t work.

Which is actually, I think, kind of cool. I like that evolution saw a use for novelty-seeking, even when you’re safe and fed. It gnaws at you.

This doesn’t mean you have to throw your phone and laptop away, sprint out the door and get on a random train somewhere. Your adventure can, and as time goes will more often, happen on a screen. You can start and finish it in your bedroom.

And people of course say ‘you gotta go and face the real world out there’, but I don’t know man. If I go somewhere online, and it makes me feel a certain way, maybe a way I’ve never felt before, to what extent is that not ‘real’? To some degree you’re just correctly using the lack of physical limitation to your advantage.

At a low level, this is actually how I think about Substack nowadays.

In that, I can look at YouTube and I see a pretty solved game. Near perfect thumbnail and title strategy. Everything gets geared toward that. It’s all under control and if you follow the rules you can succeed.

But in comparison, Substack is an absolute shitshow. And I like that. We don’t know if this place is supposed to be like twitter, or like Youtube, or like a magazine, or something new entirely. As much as I think this blog is relatively coherent in its big ideas, I am slightly making my strategy up as I go.

Who knows when we’ll work out how this actually should work? I know we’re all trying, but I personally hope it’s not for a little while longer.

I think it’s worth finding unsolved games and playing them. You’ll look back on it fondly. The next generation will read about it and think it’s cool how difficult it all was.

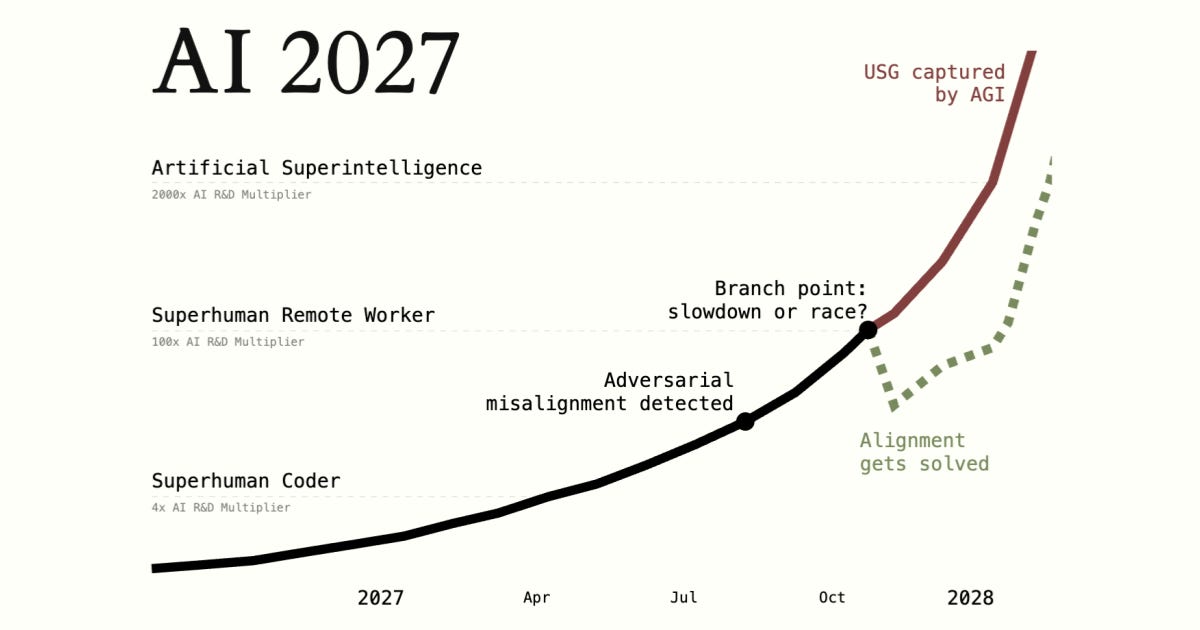

And hey, speaking of crazy adventures, think I might have found one for you:

“…happiness clearly isn’t the point of living. Living is the point of living.”

Bold claim. Citation needed/big if true/utilitarians in shambles/etc.

Advice for the young making big choices in life: take approaches that increase the variability of outcomes. Your wins have the potential for exponential upside, while you still have plenty of time to recover from all but catastrophic losses (so, yes, you still need insurance, contingency plans, etc.)

This reflects my appreciation of a fairly recently cultivated hobby of partner dance.

A dance is no-strings romance. You take a lady, perform a narrative arc depicting the push and pull and erotic exploration of flirtation, and then the song finishes and you do it again. No words, which means no memes, yet the precision and clarity in physical communication is paramount to cocreating a beautiful work of artistic expression. Beautiful not meaning perfect - recovery from an awkward cadence or fumbling leading to unexpected positioning is part of the arc. You can choose to not talk, and there are no expectations before and after the class or party ends, you just walk out the door with no hanging developments after, just appreciation for having an evening full of life - many interesting arcs with many partners who you may never see again.

Meanwhile you're performing a defiant rebellion against contemporary hegemonic ideology of androgyny as the ideal - gender roles are distinct and complementary, and each is genuinely appreciated for performing their part well.