What #corecore was actually about

aka 'why weirdness and powerlessness are correlated'

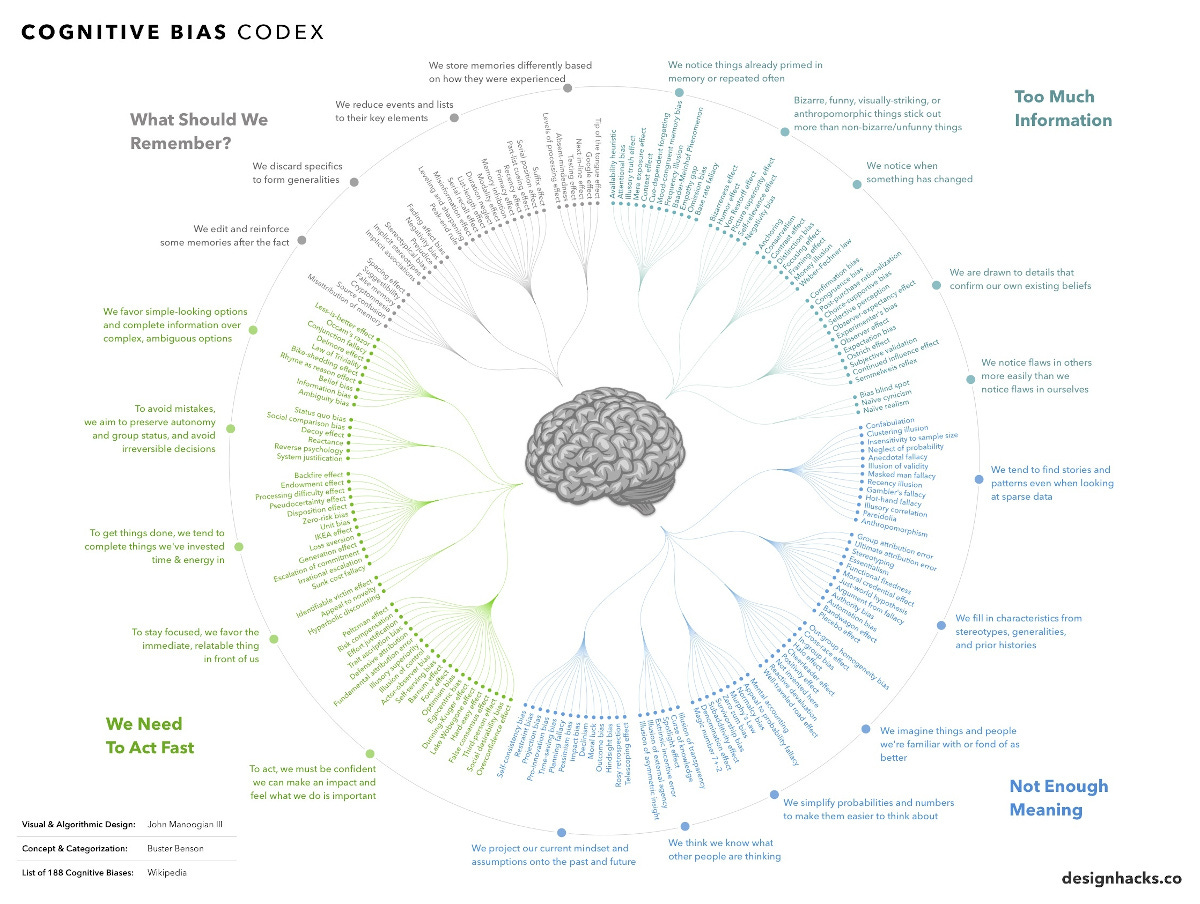

Everyone knows about cognitive biases and heuristics.

Confirmation bias and recency bias are firmly in the public vernacular, and we all once almost finished Thinking Fast and Slow. This very shareable infographic puts the total at 188 different ways people systematically make errors in their judgements.

The idea that people act weirdly under uncertainty set the foundation for the creation of an entire industry, but things look like they’ve got out of hand a bit. 188 seems like too many to be useful, and plenty of people seem to agree. How do we narrow it down?

Earlier this year, one of the most compelling behavioural science papers I’ve read in years was published. Aileen Oeberst and Roland Imhoff’s ‘Toward Parsimony in Bias Research’ has a blunt argument: a lot of cognitive biases can be explained by the fact that humans hold onto a certain handful of beliefs very tightly, as listed in the left column here:

The argument outlined is compelling. Forming beliefs about the world seems to be absolutely ubiquitous to the human condition, and once we have them, we process things around us in favour of reinforcing them, rather than questioning them. The exact way this reinforcement happens depends on the task at hand, so you get different biases that are different means to the same end. I pretty much buy that.

But then the paper … ends.

I thought the fun was only getting started? I can accept the empirical evidence that people want to be seen as good, to feel like they understand the world around them, to feel like they’ve made the right choice in what social group to identify with. But whose invisible hand paints that picture of how cognition works? If the table above was to add another column to the left, identifying the reason for people being so sensitive to these beliefs being destabilised, what would go there?

In other words, why are we angled towards continuing to see the world in the ways we’ve accepted, even when it’s irrational to do so?

To begin to answer that, I need to go a bit back in culture.

Starting with one year ago.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

2023 started with #corecore.

It turned fragments like those above and curated them into purposely calm but unsettling slideshows. People loved it, especially the critic class.

Here’s some analysis from around then:

Artnet: “Consider [#corecore] meaning-making via doom-scrolling, perhaps—an attempt to locate a center amid a disorienting, algorithm-powered digital existence.”

Time: “The whole point of this stuff is to create something that can’t be categorized, commodified, made into clickbait, or moderated—something immune to the functions of control that dictate the content we consume and the ideas we are allowed to hold.”

Vice: “I think it was satirising our internet culture, capturing that feeling of it just being too much - when you want to just delete your social media, throw your phone in a lake and go live in a hut in the wilderness, you know?”

If we were dealing with a figurative dart board, I think these would be hitting that green bit around the bullseye that’s worth like 25. Close enough to be useful, but sadly just turning up the dial on the abstractness and mysticism with which you talk about TikTok videos doesn’t earn you that last inch. Not enough to impress your date that wasn’t really feeling Flight Club in the first place.

If you want to understand whether the psychological underpinnings that kicked off #corecore are something you need to care about, and where that sees us moving into 2024, I can’t help but feel that you need to push a bit further.

Are people trying to ‘centre’ themselves, or are they trying to become ‘uncategorised’, or is it the cabin in the woods thing Vice told me?

Here’s the key question: what would the point of any of that be?

We’re gonna have to go further back.

Let’s look at some paintings together. 5 seconds each.

André Breton was one of those mythical types of people you don’t get as much anymore. In a decade, he managed to go from studying medicine, to fighting in World War I, to founding the Surrealism movement. His dating app profile would have gone crazy.

In his Surrealist Manifesto (1924), he writes “Let us not lose sight of the fact that the idea of Surrealism aims quite simply at the total recovery of our psychic force by a means which is nothing other than the dizzying descent into ourselves, the systematic illumination of hidden places and the progressive darkening of other places, the perpetual excursion into the midst of forbidden territory”

I’ll try put it simpler: surrealism is about making the familiar unfamiliar. Taking things you know and presenting them in a way that doesn’t make sense anymore. And using that to reveal… something else.

In that quote he’s talking about the other hot topic in 1920’s Central European intellectual circles: the unconscious. You may not be too surprised to find out that three years prior to publishing the above, Breton had travelled to Vienna to meet Sigmund Freud, just as Freud was fresh off publishing something very influential. Influential to Breton, anyway:

“The uncanny is that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and had long been”

It’s no coincidence that an artistic movement based on the concept of eliciting emotion by presenting things in an unfamiliar way, in a surreal way, came just after psychology had begun to examine how weird everyday experiences of disorder carry a special discomfort.

Separating out the important bit:

“… what was once well known and had long been”

To Freud, the uncanny is the feeling you get in your stomach when something you believe about yourself and about the world is threatened by new information.

Here’s a scenario. You have a Tesco Express around the corner from your house.

Due to that weird balance between convenience and lack of cohesive planning in your life, you end up in it twice a day. You know it so well that you can enter, shop and leave without really having to be conscious through the process anymore.

Tomorrow, you walk in and you feel something’s off before you even realise. Everything’s … reversed. The fruit and veg starts on the right as you enter, rather than the left, you need to move anti-clockwise rather than clockwise to reach your final destination of the checkout, where the shop worker smiles at you as usual, like nothing’s changed.

This isn’t a problem really is it? It’s not what your brain predicted, but you’re not paying any kind of consequence, you have the same shopping as usual.

But when you head back down the street, you still feel disturbed, not because of what Tesco have done, but because of what they revealed. When something familiar becomes unfamiliar, when the rules are broken, there’s a part of people that starts to see the scaffolding. We have ideas of how the world around us works, that we feel very certain about, and the surreal is that which throws that into doubt.

And think about the process of the reversed shop more, what was usually unconscious has become conscious, and it’s a problem your brain wants to sort out quickly.

How about some more extreme examples? A house that fails to be lit by a bright sky, or a horserider that’s both behind and in front of a tree, or a sun that’s somehow setting in front of a forest? I can’t use those, Magritte claimed them decades ago.

I’m afraid of losing your attention, so let’s do some modern examples. What are some random ways in the current world where things just don’t add up, where one thing just doesn’t go with the other, where something presented to you as sensible is really anything but?

What about having a gift shop at a gun range?

What about taking the time to read PornHub’s terms of service?

What about using up all your free articles before you got to read an op-ed on How To Feel Alive Again?

How much strangeness and absurdity do you need staring you in the face to start to realise how artificial the meaning you apply to everything else is?

That’s what #corecore was about.

“The situation in which a person, imagining fondly that he is in charge of his own destiny, is, in fact, the sport of circumstances beyond his control, is always fascinating. It is the essential element in most good theatre from the Oedipus of Sophocles to East Lynne. One goes into the business believing his eyes to be wide open, whereas, actually, they had been tightly shut. The galling part was that he had failed for so long to perceive the fact. He had been transferred without his knowledge from the role of sophisticated, impersonal weigher of facts to that of active participant in a melodrama.”

So, the second important question, why now?

Let’s check in with the media.

The other thing that #corecore especially gets at is that there is a particularly disturbing type of powerlessness that comes from the realisation that the technology that’s promised to save you isn’t yet living up to its promises.

You hand over your data and privacy, you expect happiness and health. You get a those weird rotating selfie cameras in Times Square instead.

The goals of the individual consumer and the goals of the tech company are often correlated, but every now and then it feels a bit divergent, and that’s where the uncanny is exposed.

See, my hot take is that there was nothing special about January 2023 in particular that produced #corecore. Maybe darker months lead to darker thoughts, but that’s the most I’ll allow you. Specific trends come and go, but the forces driving them operate much more out of sight.

This week, Digital Native gives us 7 ways the internet is going to make us feel strange in 2024:

Pixar for Everyone: Advances in AI and online tools will democratize the creation of professional-grade content, making high-quality visuals accessible to all.

AI Friends: The rise of AI companions will redefine social interactions, with AI entities becoming part of personal networks.

Personalized Ads: AI-driven advertisement will become highly personalized, leading to unique and tailored marketing experiences.

Pseudonymity: Online identities will increasingly diverge from real-world identities, fostering a culture of pseudonymous interactions.

Deepfakes & AI Everything: The use of AI in creating convincing fake content will proliferate, impacting various aspects of society including politics and personal interactions.

Infinite Generative Worlds: The entertainment and gaming industries will shift towards infinitely generative and interactive content, influenced by user input and choices.

Cambrian Explosion in Entrepreneurship: AI and digital tools will catalyze a surge in micro-businesses and self-employment, altering traditional work and career norms.

Everyone knows about the uncanny valley. But what about the uncanny valley of everything?

Kyle Chayka writes: “In the world of Full Generative AI, as the tech companies are proposing, everything falls into the uncanny valley. It will be increasingly hard to tell if an image is man-made, or if a memo written by a coworker, or if a clip of someone’s voice was recorded from reality. The replicas will improve so much that it will take time and effort to determine in each case to what degree a piece of content is organic.”

An environment that looks a little bit different than it did yesterday is a little troubling psychologically, but an entire world where humanity’s place is suddenly consciously being questioned? That’s really going to push some System 1 information processing capability.

And it’s a big clue as to why #corecore matters now, but it’s still not getting to its consequences. Let’s continue.

There was another group of people that came to the fore in mid-20th century Europe worth mentioning, who directly addressed something I’ve been dancing around here.

Existentialism, meaningfully beginning with Soren Kierkegaard, puts existential angst as central to the human condition. Kierkegaard had it that the individual’s confrontation with the uncertainties of existence, and the realisation that everything’s kind of up for grabs, produces a dizziness of freedom. This infinite potential clashes with the human need for order and meaning, in a universe that just seems indifferent to you existing, producing a weird feeling. What word shall we choose for it?

On the back of the first world war, we had Breton’s ‘surreal’ and Freud’s ‘uncanny’, and by the end of the second world war, we also had Sartre’s ‘nausea’ and Camus’ ‘absurd’. We can add Bo Burnham’s Funny Feeling too.

So going all the way back to that paper claiming a huge chunk of biases can be distilled down to a handful of basic beliefs. The extra step is saying that these beliefs all come from one central psychological problem: When you are born, you aren’t told who you are, and you’re definitely not told what you are supposed to be doing with yourself for 80 odd years. So you unconsciously get to work building answers to those questions on the fly. If we’re being honest, it’s kind of your only option.

So to use Sartre’s turn of phrase: existence precedes essence.

Everyone who ever walked in Phil 101 has heard that catchphrase, but their friends who chose to take Behavioural Econ 101 missed the memo. Maybe we should offer them it’s psychological cousin:

Motivation precedes cognition.

This is the same conclusion that (the legendary) Arie Kruglanski and co-authors reached in 2020 when they published ‘All Thinking is Wishful Thinking’. The paper’s argument goes: Thinking and learning aren't just about gathering knowledge; they're also driven by our needs. Our quest for understanding is shaped by our underlying desires, like wanting to feel sure about something. This influences how we take in new information, how sure we feel about what we believe, and how much we look for more information.

This goes back to an idea central idea in Kruglanski’s work, which is mirrored in a different font in far too many theories for me to cite here, that people have a drive toward cognitive closure. In one less word, certainty.

“People can abandon any attempts at personal experiment out of the conviction that they already know what any experiment with their own lives will lead to. For making things coherent means imagining they are known and understood by the simple act of an individual's will. This leads the young person to enter adult life in a state of bondage to security, in a self-imposed illusion of knowledge about the outcome of experiences he has never had.”

Once this is your starting point, some other pieces start to fall in place.

If you really want spend time (and charge dumb academic paper money for) debating what the difference between confirmation bias and motivated reasoning is, it might be worth starting with an examination of what you consider reason to be in the first place.

Actually, don’t even sweat it, because Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber did that half a decade ago. The argument goes: Humans’ biggest advantage over other species is our ability to cooperate. Cooperation is difficult to establish and almost as difficult to sustain. Reason helps us justify our beliefs and actions to others, and it is more about convincing others and evaluating arguments than about finding truth or being logical.

So explain to me how ‘motivated reasoning’ and ‘reasoning’ have different Wikipedia pages.

All thinking if wishful thinking. And we’re very good at it.

Let’s take a quick look at perception too, led by Bobby Duffy this time. When we build our conception of our environment, what goal takes the lead, accuracy or the feeling of accuracy? The Perils of Perception is a pretty cohesive account of not just how often we are wrong about basic facts about the world around us, but how we do it with confidence. How confident? I’d say certain.

One last thing, when certainty is threatened, how do we readjust? The Meaning Maintenance Model (a spiritual successor to Terror Management Theory), offers a general answer from existential social psychology

Part of the MMM suggests that in response to the discomfort caused by disrupted meaning frameworks, individuals tend to respond by affirming other, intact meaning frameworks.

This affirmation serves as a way to compensate for the disrupted meaning and restore a sense of coherence. In short, when one part of your life looks strange, you cling to the parts that have remained stable, to keep things feeling coherent. (Hey, I think I have an extra hypothesis for this Nature paper on nostalgic Spotify streaming during Covid lockdowns.)

And something less novel, a heightened need for closure off the back of cultural threat is associated with increased extremist tendencies. If you threaten someone’s sense of what their environment should look like, expect them to come back at you much stronger.

But existentially based models of reasoning and perceiving (which I know you feel somehow don’t apply to you) aside, why certainty? Cui bono?

The likely answer goes back to Kruglanski again.

In the same way you must be motivated to think and reason, you need certainty in order to act at all.

Ask Fyodor:

“You know the direct, legitimate fruit of consciousness is inertia, that is, conscious sitting-with-the-hands-folded. In consequence of their limitation they take immediate and secondary causes for primary ones, and in that way persuade themselves that they have found an infallible foundation for their activity, and their minds are at ease and you know that is the chief thing. To begin to act, you know, you must first have your mind completely at ease and no trace of doubt left in it. Why, how am I, for example, to set my mind at rest? Where are the primary causes on which I am to build? Where are my foundations? Where am I to get them from?”

And if you need certainty to act at all, then you shouldn’t ask how young people could be associating weirdness with powerlessness. How could they not?

The interactions of technology and people being represented in #corecore aren’t just a realisation that the goals of technology and the goals of the human endeavour aren’t fully aligned now. It is a realisation that we are some way along a graph that started quite a while ago.

So the manifestation is not one of anger, or even anxiety, because what would be the point? In Dostoevsky’s words, the direct fruit of that consciousness is inertia.

This year, the most famous paper from the cognitive revolution, Tversky and Kahneman’s ‘Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases’, passed 50,000 citations. Behavioural science was built on being obsessed with how people deal with uncertainty. But I think there’s a different framing, just how far will people go to avoid it in the first place? And here’s the question no one asks: what happens when 8 billion people do that at the same time?

In an existence that is inherently uncertain, we’ve become built to find order in the incoherent, to feel we know who we are and what we are supposed to be doing with ourselves. My ultimate fear is that #corecore represents the start of an era where that power starts to run out.

The drive for certainty results in some beliefs we hold tightly around being good, around being of a superior group, and around being able to make accurate judgements of the world around us. And to defend those beliefs, our behaviour can manifest in various biases and heuristics. They may cause us to slip up in some predictable ways, but ultimately, that’s not really the point.

And then even when we encounter things that truly shake up our regular thinking, we find ways back to meaning and coherence with time to spare. A lot of the time, we come back with even stronger convictions than before, now we’ve learned to be on the defensive.

Every variable in the world around you is moving all the time, but it’s a pretty remarkable achievement of cognition that to you, it never really feels that way.

At least, not at at the moment.

But I can’t help but wonder what happens when those variables really start moving fast.

When the narratives for what we’re all supposed to be doing with ourselves collapse in a way where we can’t just pivot our attention away to what we do know to be true…

How’s that all going to make you feel?

I think we can make a pretty strong guess.

Another VERY interesting post!

(Im aware that this comment is probably too long and with too many references. Ignore anything that is not worth the time.)

I've been reading and thinking about the accelerated speed of change. And I even written a bit about it:

- In Maven: https://app.heymaven.com/discover/1192777

- In a couple of Summer of Protocols's forum posts: https://forum.summerofprotocols.com/t/cryonics-law/1499/3 / https://forum.summerofprotocols.com/t/the-questions-of-protocol-scales/1541

A couple of excerpts:

- McLuhan: to keep up with the pace of change, we became pattern-matchers.

- McLuhan Speaks: Pattern Recognition | The Marshall McLuhan Speaks Special Collection - https://marshallmcluhanspeaks.com/soundbites/pattern-recognition

- Robb: When social media arrived, we forcibly packetized our media into bite-sized narratives to catalyze pattern matching.

- Now we know that packetized media fuels networked tribalism.

- Packetized Media: [partially paywalled post] Packetized Media - by John Robb - Global Guerrillas https://johnrobb.substack.com/p/packetized-media

> I’m thinking about [...] when changes become so fast that it goes beyond our “fastest rate to process changes” and it all becomes blurry, with no signs to slowing down. The problem here is not any specific change and how we adapt to it. The problem is the always-increasing part of reality that we have no time to process.

Another tangential reference that came to my mind is Poteat and Polanyi's Post-critical philosophy which I would summarized (probably incorrectly) as "knowledge is always personal, and the observer (processes) are as important as the object (reality) under study".

FYI: The link to "Terror Management Theory" is broken. The correct one is: https://www.ernestbecker.org/terror-management-theory/