You’re (even more) on your own from here

Technology and individualism

(Disclaimer: Reading previous posts on growth and on certainty would be useful but by no means necessary. Also, this used to be one giant post. I no longer think that was a good idea. So, I’ve changed it to a mini series, with posts as chapters, because I think it makes it more readable. Hope you agree, and happy 2024.)

Everyone wants to know what the differences between the generations are.

And plenty of people have answers for them.

But I think a strong signal that the internet fails to provide a clear answer to something is if it ends up with a lot of upvotes on r/NoStupidQuestions:

So, what does Reddit have to say that pierces through the marketers and news aggregators:

Hotdog semiotics aside, dividing people up into generations is evidently big business. Otherwise there wouldn’t be half as many people asking, or a quarter as many answering.

What’s also evident is that this big business is treacherous territory for people who have the word science in their bio. So, to exercise some caution, let’s appeal to authority and stick to the academic literature.

Dr. Jean Twenge released Generations this year, and reading it would save you a lot of time. Twenge has been among the leaders in understanding generational data for three decades, and this book is the most cohesive combination of the data available that allows you to step back and decide what really is going on.

Good news, the headline result is that generational differences are actually real, and not just a story we’re telling ourselves. Millienials are more optimistic on average, Gen Z are less confident. Gen Xers are disproportionately accepting of differences. No one from other generations reads this substack so let’s agree they caused all of society’s problems.

But it’s where and why you draw the dividing lines that things get interesting.

Here’s where Twenge thinks the lines are:

Silents (Born 1925-1945)

Boomers (Born 1946-1964)

Gen X (Born 1965-1979)

Millenials (Born 1980-1994)

Gen Z (Born 1995-2012)

Gen Alpha (Born 2013-tbc)

The why is trickier, and to be honest I think you should distrust anyone who claims they know exactly why any generation are the way they are, but with enough data you can turn down the opacity quite a bit. So let’s see how Twenge does that.

Initially, a dominant way of thinking about what defines a generation is to think about what major events occurred in their developmental stages. We’re talking wars, recessions, booms, regime change. If you’re trying to work out who you are, and how you want to spend your life, this would clearly be a factor, right?

Test it out. Close your eyes and imagine living through the 1910’s.

The logic is that exposure to this completely different economic, sociological, cultural situation would shape your perception of the world and your place in it. On a population level, this leads to small, but meaningful differences between groups that were born at different times.

But in reality, this is completely neglecting the factor that comes first.

When you imagine yourself living through those periods, your brain cuts a corner. You take your sense of how you currently interact with major events, and all you do is change the event itself. I guess you were probably imagining life as more sepia-toned too.

What you also needed to change was how that interaction with historical events would have worked. The people on the ground during any important event obviously get their psychological consequences from the source. But what about the people living in different cities, in smaller towns, that don’t see it with their own eyes?

The answer to that question depends on when you were born. And that really matters. Yes, I can believe that exposure to economic, sociological, cultural factors shape your perception of the world. But the nature and extent of that exposure depends on a bigger factor: technology.

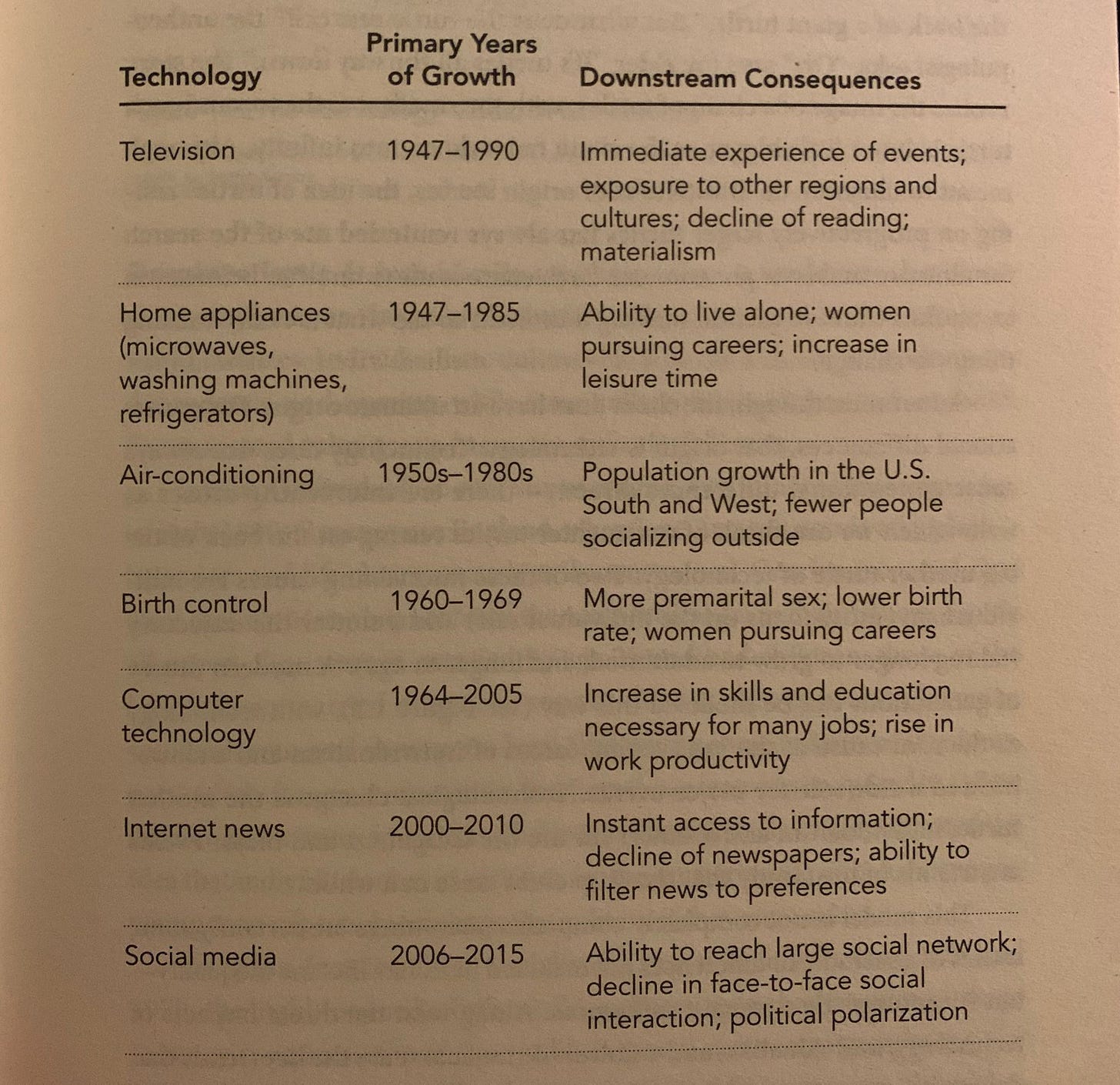

That was a roundabout way of telling you that Jean Twenge posits that technological advancements, rather than major historical events, are the primary drivers of generational change.

Boomers never had a childhood without TV. Gen X never knew life pre-computer. Millennials watched the internet grow up, and the internet watched Gen Z grow up in return. Now, Gen Alpha will never know what it was to exist without artificial intelligence.

This matters to individual psychology (and when multiplied out, to culture) in two ways:

Technology generally replaces a job previously done by humans, meaning you need other people less (and they need you less in return).

Technology gives you the time and freedom to develop yourself beyond the bounds the previous generations were restricted by, meaning an increased ability to live the life you want for yourself.

Here’s a map:

In both consequences of technology above, your dependence on others and their dependence on you decreases. Maybe that makes it less surprising that different generations have different conceptions of what it is to be a good contributor to society, because they were all told different things about what a society is. You scratch my back, I scratch yours. Until I don’t need you to anymore, now how do I participate? I guess I’ll have to work that one out on my own.

So the next time you’re on r/NoStupidQuestions asking how long you could survive in a microwave for, and you notice people stressing about generational differences, tell them this: Technology largely defines generations, and technology enables individualism, always.

So, let’s talk about some technology.

In one of this platforms greatest posts, Erik Hoel’s ‘Why we stopped making Einsteins’, historical figures are analysed to reveal a weird trend. As education became ubiquitous, and systematic, the ability of the average person flew up. But there was a catch, for every teacher that now has 30 kids to explain calculus to, there’s one less highly privileged child that would have had their own private tutor for everything. This was a good move to make, school is good.

But the reason that post gets its name is because in that old unfair system, where some get specialised education from birth, a minority really got rewarded for their good fortune. Hoel’s work is actually robust compared to my summary here, so don’t hold this against him, but here’s two examples for brevity:

Bertrand Russell

The famous 20th century philosopher and mathematician, was raised by his wealthy grandparents and didn't attend school until age 16. Instead he had a "revolving door" of private tutors, many of whom were impressive intellectuals themselves. This individualised study helped shape Russell into the genius he became.

John Stuart Mill

The "clearest example in history of a genius constructed by tutoring." Mill's father, an intellectual himself, purposefully kept Mill away from other children and instead rigorously home-schooled him with the explicit goal of moulding him into a genius philosopher. Starting at age 3, Mill absorbed the classics and higher level subjects under his father's strict daily supervision. Mill's eventual status was that of a titan of 19th century philosophy, economics, and politics.

What does this have to do with tech? Well,

I personally think people should be very excited about what’s about to happen to education. Like, if you’re a lecturer concerned that your undergrads might be using ChatGPT to complete their pointless mid-term essay, I think you have bigger problems. Or opportunities, use your own judgement.

The internet has had almost all the knowledge for a long time, but the issue is that it’s unstructured. If I want to become an adequate physicist, I can try starting with a Google search, but I’m shooting in the dark. So someone that structures a course, and then tells me I’m doing the thing good, is useful. But if that someone can: (i) do that without requiring I take out a crippling loan, (ii) be there on demand whenever I need them, (iii) deliver that within the confines of my room, (iv) personalise the course to my specific ambitions rather than the average of 200 other students? Well, I’m listening.

And now you’re telling me it could rapidly speed up my learning as a bonus?

Wow, independence really is beautiful.

It seems to me that the future of AI products is this level of hyper-personalised, to give your life the highest potential possible. To be honest, that’s not even it. The present of AI products is that of the hyper-personalised, they’re just going to get better.

Travis Scott’s album didn’t live up to your expectations? Just make your own one, man.

Need to practice for a big job interview? You can just simulate your specific scenario now instead.

Sam Altman has a few more ideas along these lines:

Whatever issue you encounter in daily life, you are dealing with made-to-order solutions, just for you.

Here’s Digital Native on hyper-personalisation, in a much more cohesive way than I will attempt here:

“Hyper-personalization is one of the largest decades-long shifts. We see it appear in culture, where our expectations have become personalization; we’ve gotten spoiled. And we see enabling technologies like AI arising to make new degrees of customization possible. Soon, everyone should get their own personalized healthcare plan; their own personalized learning path; their own personalized shopping recommendations.”

The interesting new thing is that now we want experiences themselves to revolve around our personal preferences too. The consequence of this is that what starts with not sharing a teacher anymore, is all building towards not sharing anything anymore. Technology enables individualism. Experiences built in your own image, decided in advance.

Imagine the scene. Game of Thrones makes a surprise return in 2030 for Season 9, and with the power, efficiency and possibility of generative AI, the show-runners go all in on new production tools.

It’s premiere day, popcorn’s ready. Hopeful of restoring your old fond memories of what made it temporarily your favourite show ever, your dopamine engine starts firing immediately, building to a crescendo of release when a character does something sensible and kills an enemy standing right in front of them. Showbiz is back, baby.

You message your friend, who you had always disagreed over the world’s ethics and politics with, happy to have one over on them.

‘Told you bro, there’s no way Tyrion was ever going to survive that’

And your arrogance is met with the response

‘wdym, he survived in the episode I watched’

Good thing you don’t need other people that much anyway, right?