Cultural Moloch

the speed depends on the destination

Last year I wrote a post called Culture is a System. I came across it recently. I think the main points hold up, it’s just so needlessly long and quite badly written. So I made this very condensed version.

If you read that old post already, you can skip this. And if you haven’t read it, and think any of the points made here are jumps or underdeveloped, you can still read the long version here.

I.

Many people argue that culture has become homogenised and boring. Everything hangs around strangely close to the median, and that median isn't very thrilling.

So what's causing it?

Some standard explanations:

"Capitalism, but also laziness and mental vacancy, allows the powers that be (Corporations! Algorithms! Influencers!) to tell you what to do."

"Users of technology have been forced to contend with data-driven equations that try to anticipate their desires—and often get them wrong. What results is a state of docility that allows tech companies to curtail human experiences—human lives—for profit."

"The key factor can only be what happened to us at the start of this century: first, the plunge through our screens into an infinity of information; soon after, our submission to algorithmic recommendation engines."

Given the subject matter, you have to admit it's quite ironic how alike these all are. But this sounds like a closed case right?

Capitalist society → You are monetizable → Algorithm's goal is to keep you engaged → No room for things the algorithm doesn't understand.

But within those quotes there is a big clue telling you that something big remains unsolved. Here's a psychoanalytic heuristic that might be useful in future: if a thesis that is implied to be some kind of brutal truth allows you to feel good about yourself, then it is likely neither brutal nor true.

Because what gets left out of every single piece of analysis of cultural stagnation, without fail, is an actual psychological analysis of the actors within the system. Every single time, the sameness is diagnosed, and the buck is passed to some greater force. Which means it can't be your fault.

This is precisely why these theories are all wrong. At best, they are severely incomplete.

Also, I use the words 'actors within the system', I could just use the word 'us'. The people that create culture, that live culture, that know no existence without culture. I'm sure they'd be offended to find out the NYT thinks an algorithm has stripped them of all their passion under their noses in service of Silicon Valley. I know I was.

And with that misunderstanding in mind, I can say with confidence that calls to revive culture will invariably fall on deaf ears. Because culture is very much alive, it just has its own agenda, and it is always going to win.

II.

I mean something specific when I say 'the system'. It's not capitalism or democracy or some shadowy cabal. The system is just 'the way things turn out' - the aggregating of everyone's desires. And I'm deriving your desires from the things you do, not the things you say.

The system is not 'them', it is 'us'. And you can't just leave.

Let's start simple. I want to get in shape. But it's cold outside and I'm hungover, so I order Uber Eats. To me, I still want to lose weight. But to the outside world, the correct conclusion is that I want to put on weight. Because all anyone can see is my behaviour.

Spread this out to a population. I love music but can't afford what Spotify would need to charge to pay artists fairly. So the system wants streaming that leaves artists worse off. Not because it wants artists to lose out - it's just trying to fit everyone's wants together.

This systemic outcome, while not explicitly desired by any single actor, is the cumulative effect of combined desires and actions. There's no strings being pulled. It's just us here.

When we expand this out to culture and society at large, what do we all silently agree to compromise on? What gets lost along the way to optimization?

The answer involves understanding incentives and competition. Sometimes there isn't enough to go around (e.g. not everyone can gain status at the same time). When we have separate interests and have to guess at others' behaviour, the rational thing is to act fully in your own interest.

This is basic Game Theory. Competition hurts cooperation, and individuals have incentives to act in ways that create sub-optimal outcomes for the group.

Now imagine 8 billion people with various incentives, where not everyone can win. What sub-incentives can you not afford to care about if you want to ensure you don't get screwed?

III.

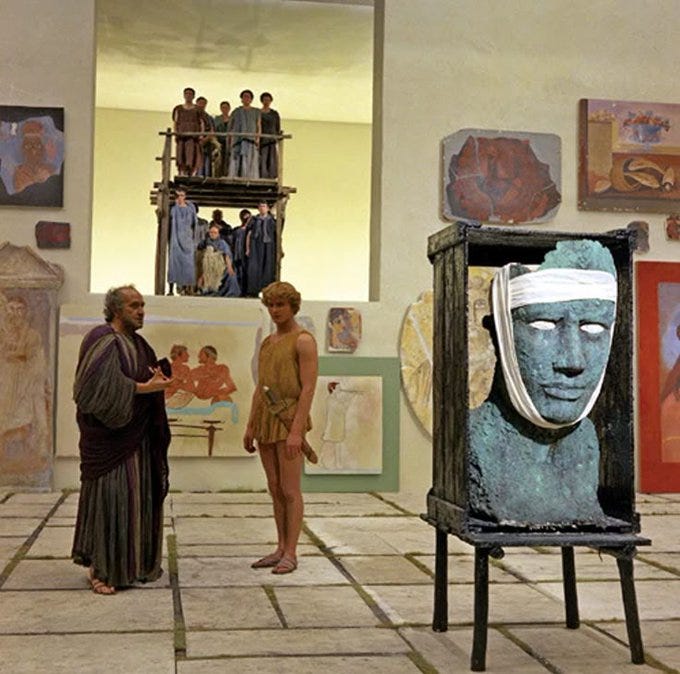

Scott Alexander's "Meditations on Moloch" explains how systems compel entities to prioritise their own survival, even at the expense of the greater good.

Here's how it works: When competition is a permanent threat, the coordination required to stop us breaking our backs to succeed becomes impossible.

Take TikTok creators. 100 people share 1 million viewers equally. One starts their video in underwear with trending music. They steal everyone's viewers. So everyone else copies the tactic. Within 24 hours, they all have equal viewers again - except now they all have to do more just to maintain the same position.

Or defence spending: countries spend 5-30% of budgets on missiles that sit unused, because any country that doesn't risks invasion. From a god's-eye view, world peace would be better. From within the system, no country can unilaterally enforce that.

As Scott puts it: "In some competition optimizing for X, the opportunity arises to throw some other value under the bus for improved X. Those who take it prosper. Those who don't die out. Eventually, everyone's relative status is the same as before, but everyone's absolute status is worse."

This is Moloch - the crippling force of coordination failure. When you see competition within a system, expect values to be ditched to optimise, and expect no one to be better off in the end.

Now, how does this create cultural homogenization rather than constant innovation?

Culture develops through memes - ideas that leap from brain to brain. But not all memes survive. The ones that are stickiest earn a place in collective consciousness. Just like genes, memes compete for replication, and only the most viral survive.

So we get highly spreadable memes that dominate how we behave and think. Every sport, restaurant style, art form - these are memes that left less catchy ideas in the dust.

Cinema is a perfect example. Infinite possibilities exist, but films fit into select genres with handful of storytelling techniques. They're all operating within a narrow window of what we agree movies should be like.

This happens because they're in competition. It's survival of the fittest.

Culture is competition. It has winners and losers, and the prize is a place in consciousness. We can't see the losers because they live outside our memory.

IV.

Combining memetic competition with Molochian dynamics: One meme works out an advantage, and the rest must follow suit or die. This process means they all shed parts of their makeup to stay afloat. Then another meme finds another advantage. Everyone loses a second value.

The closer memes get to optimized virality, the more they have to look the same. Anything else is a risk.

So what are the characteristics of an optimized meme? What does the brain like to see in cultural information?

The answer is essentially just familiarity. There's a robust psychological effect called mere-exposure: people develop liking for things merely because they are familiar with them. The more you interact with someone, the more you tend to like them. Repeated exposure to unfamiliar music leads to more positive ratings.

Familiarity breeds liking. And crucially, this effect is strongest when you don't consciously realize it's happening.

If you use TikTok, you've probably hit like before consciously perceiving what you're watching - and it was probably a meme you'd seen 10-20 times before. You've probably finished a session unable to recount anything you saw, but your brain got its dopamine hit.

This would happen even if TikTok went non-profit and tried to diversify your feed. Because your brain likes what it likes, even if we don't like the aggregate outcome.

Why do we unconsciously prefer the familiar? Because once you're fed and safe, the real human goal is certainty. Familiar things have already been factored into our representation of an uncertain universe. They fit the model. Novel things don't, they remind us that nothing is certain, which is psychologically threatening.

Technology affects this dramatically. In a prehistoric 50-person society, memes could be rough around the edges. It was a finite game.

Technology makes this game infinite quickly. It converts 20 games in 20 stadiums with 4,000 seats into one game with 80,000. The standard to be a player becomes higher. Anything that's not a well-oiled, easy-to-reproduce meme won't survive. So what can't survive? Detail, variety, novelty.

And the bigger the competition, the less capacity memes have to care about anything other than familiarity.

Cultural variation isn't the outcome of the system, it's proof of resistance within it. Technology hasn't created a new system with different goals; it's just pulled all the resistance out of the old one.

V.

You can't just leave this situation. No amount of counter-signalling or algorithm cleanses does the job. That's still playing the game. Leaving would mean heading for the outback, living off the land. But someone else owns that grass, you're getting charged for rough sleeping, and the police officer doesn't care what you've opted out of.

You're stuck.

Let me map out what I'm saying. Cultural flattening is driven by memetic processes where the most recognizable things reach the top. This is the aggregate of our collective wants. We are all complicit.

There are two issues preventing anyone from solving cultural stasis:

I. The insistence that someone else is doing this to us.

II. The idea that algorithms prevent people from doing what they really want.

But when you commit to an algorithm cleanse as part of pursuing your ideal lifestyle, where is that picture coming from? A Patagonia ad?

Most people accept that the system tells you what to want. But the more important process happens first, when the system teaches you what it is to desire something in the first place. You define who you are by your place within the system. And you can't just leave.

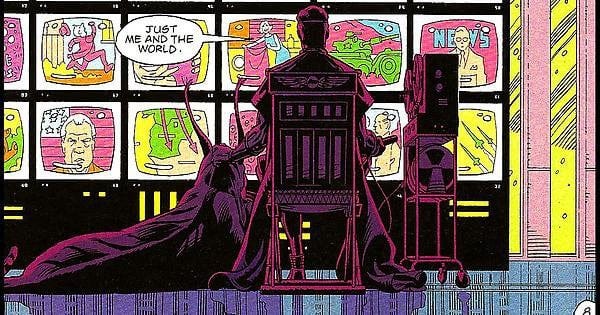

And so I present to you the grand irony of culture of the 21st century. From the same system who brought to you ‘Goods That People Buy But Wish Did Not Exist’, I give you: ‘The Main Characters Who Became NPCs’.

The system optimizes itself towards you, but it's also feeding you the ideas of what you want in the first place. When we all have no flaws, we'll all look the same. So will our coffee shops. So will our cars.

Algorithms flatten culture because to the system, this is optimization. It thinks it's serving us, but that's how we've told it to serve us.

Who's responsibility is it to save us? Don't let the ego play one final trick. Don't hope for some new digital era where joy returns. Don't think someone is pressing this stasis upon you.

It's not Sam Altman, Google, TikTok, Elon Musk, Biden, or Murdoch.

It's the system they're all part of, which happens to include you.

And you can't just leave.

I think you described evolution creating tapeworms or some other intestinal parasite. Everything unnecessary stripped away.