Culture is a System

And the purpose of a system is what it does

(warning: long, and contains rationalism, metaphysics, critical theory and #ootd TikToks)

Alice: “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

The Cheshire Cat: “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”

Alice: “I don't much care where.”

The Cheshire Cat: “Then it doesn't much matter which way you go.”

Alice: “...So long as I get somewhere.”

The Cheshire Cat: “Oh, you're sure to do that, if only you walk long enough.”

Ariana Grande dropped a new song this month. What’s interesting is that nothing about it sounds new at all.

‘yes, and?’ is an 80s-ish club house track, and is the first single in over 3 years from the 3rd biggest artist in the world. Sounds like a good formula for a hit, especially when the most-streamed song ever on Spotify is a cross between modern pop star and 80’s synths.

I have no opinion on the Grande song, but here’s how it made someone else feel:

For me, this is the tweet that broke the camel’s back, and why there is now this essay for you to read. Because everyone on social media is agreeing with it, and that’s a good signal that something is wrong.

The thing is, I see questions like the one above all the time. I collect them. It’s an interesting problem. And plenty of people are talking about it.

You may have been sent the NYT op-ed ‘Why Culture Has Come to a Standstill’ last October. Maybe you follow ‘lindyman’ Paul Skallas on twitter who has long been sounding the alarm for ‘Stuck Culture’. Hopefully, one thing you did come across was The Age of Average which made some waves with its relentless use of examples.

If you’re a movie person, try out ‘The creative pandemic taking over our screens’. Music more your thing? You can check out ‘The homogenisation of music: of TikToks and viral reels’. I know your a bit into style, so you must have heard about ‘The homogenisation of modern fashion’. And at the end of the day, I bet you unwind with YouTube, where you might have already come across ‘The MrBeast-ification of Youtube’ with a thumbnail reading…

As the NYT put it:

“To pay attention to culture in 2023 is to be belted into some glacially slow Ferris wheel, cycling through remakes and pastiches with nowhere to go but around. The suspicion gnaws at me (does it gnaw at you?) that we live in a time and place whose culture seems likely to be forgotten.”

And there’s plenty more where that came from, e.g. literally the first things I saw on my feed this morning:

Yes, the threat of cultural homogenisation and lack of originality is in the air. I think the evidence is compelling. A few screenshots to surely overdo the point:

Credit to Alex Murrell for the above, and see Age of Average for further examples.

Here’s the deal: products, services, places, logos, media, people etc. - all now hang around strangely close to the median. What’s also clear is that this median isn’t very thrilling. Maybe that’s because I am by default overexposed, but it makes it unsurprising that such a culture produced the word ‘mid’ as a go-to rating for stuff.

Who sees one of those cars and envisions picking up a first date in it? Who sees one of those modern skylines and thinks “Wow, I’m so far from home here”? How am I supposed to be the main character in my own story when it looks the same as everyone else’s?

Everyone is agreeing that novelty is getting lost. So what are they proposing is causing it, and do they all agree on that too?

Some opinions on what is doing it:

Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick in The Trend Report:

“There is an incredible rash of thoughtlessness, intellectually and spiritually, coming from our living unfulfilled lives chained to jobs without time to be an individual or cultivate individuality … You take a backseat in your own life, whether willingly or unwillingly … Capitalism, but also laziness and mental vacancy, allows the powers that be (Corporations! Algorithms! Influencers!) to tell you what to do.”

MIT Press’ blurb for Kyle Chayka’s new book Filterworld:

“Kyle Chayka shows us how online and offline spaces alike have been engineered for seamless consumption. Users of technology have been forced to contend with data-driven equations that try to anticipate their desires—and often get them wrong. What results is a state of docility that allows tech companies to curtail human experiences—human lives—for profit.”

Jason Forago in ‘Why Culture Has Come to a Standstill’:

“But more than the economics, the key factor can only be what happened to us at the start of this century: first, the plunge through our screens into an infinity of information; soon after, our submission to algorithmic recommendation engines and the surveillance that powers them.”

Given the subject matter, you have to admit it’s quite ironic how alike these all are. But in any case, this sounds like a closed case right?

Capitalist society → You are monetizable → Algorithm’s goal is to keep you engaged → No room for things the algorithm doesn’t understand.

But within the above quotes there is a big clue telling you that something big remains unsolved. That tells us the equation we just sketched out is covering up something else. That something else is applying the force.

I would actually say it’s screaming at you.

Can you spot it?

Here’s a psychoanalytic heuristic that might be useful in future - if a thesis that is implied to be some kind of brutal truth allows you to feel good about yourself, then it is likely neither brutal nor true. Here’s a second heuristic to fix it - swap out the word ‘brutal’ for ‘defence’ and ‘truth’ for ‘mechanism’, and you’re getting warmer.

If your response to that is along the lines of “that doesn’t make sense, why would some cultural critic spend time offering me my own defence mechanism?”, well then, you’re starting to ask the right questions.

Because what gets left out of every single piece of analysis of cultural stagnation, without fail, is an actual psychological analysis of the actors within the system. Every single time, the sameness is diagnosed, and the buck is passed to some greater force. Which means it can’t be your fault. Go back up, read the words in bold, and you’ll see it. It’s straight out of the ‘other self-serving bias’ playbook.

This is precisely why these theories are all wrong. At best, they are severely incomplete.

And yeah, when I use the words ‘actors within the system’, I could just use the word ‘us’. The people that create culture, that live culture, that know no existence without culture. I’m sure they’d be offended to find out the NYT thinks an algorithm has stripped them of all their passion under their noses in service of Silicon Valley. I know I was.

What this overlooking of human contribution causes analysts to miss is really important. They look at algorithmic trends towards the average as a sign that culture is dead. It takes a look inward to see that it is the complete opposite.

And with that misunderstanding in mind, I can say with confidence that calls to revive culture will invariably fall on deaf ears. Because culture is very much alive, it just has its own agenda, and it is always going to win.

Now I will show you what I mean.

The big idea of the last few posts I’ve written on here can be summarised as the reinforcement of self-identity being subsidised by the system that benefits from it. You ease existential anxiety by affirming who you think you are, and the world around you encourages, and is reinforced by, this happening. That’s true whether you like the current system or not.

(for further details see: 1, 2, 3, 4)

I accept that this might have alienated some readers. Because the ‘system’ is the type of language usually reserved for overconfident teenagers, stoners in American films, and Andrew Tate. I don’t think I share any of those people’s worldviews. I mean something else.

See, in their worlds, when ‘the system’ is thrown out as common vernacular, it’s always in an accusatory way. ‘The system is killing you, man. The system doesn’t know what we’re going through. We need to stick it to the system’.

What’s funny is they are all really close to learning something that will actually help them change their lives for the better, and stop blaming everyone else for how they’re feeling. The thing they are actually right about is that there really is a living entity holding you in place to serve its own interest, they just don’t understand who is applying the force. They think the system is an enemy to be fought, an opposing ideology, a shadowy group that profits off their anxiety. They probably also think it’s Rupert Murdoch, or something.

But this is all a mental sleight of hand, performed by the Freudian ego before consciousness gets involved. You give yourself someone to hate, that just so happens to let you off the hook for your own circumstances. ‘Listen, I might not have my shit together, but at least I’m not as evil as the guy putting me in this situation’. Hey, look at that, a brutal truth that allows you to feel good about yourself. Humanising it into ‘The Man’ now seems easier to explain.

But guess what stoners, teenagers, and Tate subscribers are all eventually destined to realise? Locking your mental doors to the system doesn’t make it go away. Because it can’t go away. It was never outside in the first place. This is the key difference. The system is not ‘them’, it is ‘us’.

And you can’t just leave.

I would best explain the system as ‘the way things turn out’, i.e. the aggregating of everyone’s desires. And I’m deriving your desires from the things you do, not the things you say. I don’t want to get called a reductionist, but when the sun rises in the morning, that equation is all that it sees below it. And you’re part of it. And me.

The system is not capitalism. The system is not democracy. Switch out both of those things for their opposites and a lot of what I’m about to say would still hold. Because everyone involved is still a person.

Let’s start really simple.

I, an individual, want to get in shape. But it’s cold outside and I’m hungover, so naturally I also want Uber Eats. That day I eat more calories than I burn. Now, to me, I still want to lose weight. But to the outside world, that wants to meet all of my wants at the same time, the correct conclusion is that I want to put on weight.

Because how could it conclude anything else? All anyone else can see is my behaviour. My values, attitudes, grand purposes in life - they are all internal. I can’t expect the world to build around those, especially when I’m part building the world with my actions.

Spread this out to a population of people like me. I love music and want to listen to as much as I can, but I can’t afford the fee Spotify would need to charge to pay artists the same as they made from CD sales. So, you can observe “the consumer wants all the music,” and “Spotify wants to be affordable to its demographic,” and the sum of those wants is what we are calling ‘the system’. In this example, the system wants streaming that leaves artists worse off than they used to be. So that is what has to happen. The system doesn’t want it because it wants artists to lose out; it wants it because it’s trying to fit the wants together.

I know this is relatively basic, but here’s the important part - This systemic outcome, while not explicitly desired by any single actor, is the cumulative effect of their combined desires and actions. There’s no strings being pulled and there’s no cabal. There’s not even a motive. It’s just us here.

This also means that the system can’t ‘go wrong’, because that wouldn’t make any sense. There’s no goal beyond the behaviour. The purpose of a system is what it does. Here, there’s even a Wikipedia page about it.

Sorry, that’s just what a system is. And that’s how some people get screwed. Elect who you want, they won’t be able to control it. It’s the system that elected them anyway.

And before we dive into the rest of this, here’s another trick for you. Anytime you hear someone speak about the problems of modern culture, and they’re implying that these problems are being cooked up by some shadowy forces causing our suffering, appreciate the defence mechanism. Call back to the wisest of aphorisms: “Congratulations, you played yourself”.

eg:

This time running isn’t going to get you anywhere, Forrest.

Anyway, I’m not calling my model for Spotify’s existence conclusive evidence of anything. Maybe some people on their board are dicks. The point is just to show you that it’s possible for everyone with neutral intentions to cause things they dislike. That’s obvious. But there’s a harder question at hand.

We’ve spoken enough about systems to know this much: a system is an aggregate of everyone’s wants, and it often has to make compromises to fit everyone’s wants together. Even if no one wants that compromise to be made.

The harder question is this: When we expand out to the entire system, not just music, not just my conflicting health goals, to culture and society at large, what do we all silently agree to compromise on?

What gets lost along the way to optimisation?

“Of course it is,” said the Duchess, who seemed ready to agree to everything that Alice said; “there's a large mustard-mine near here. And the moral of that is--The more there is of mine, the less there is of yours.”

No behaviour can be fully explained without an understanding of incentives. An incentive is something you want that you have to do something to get.

Your boss understands this. Your therapist understands this. And your government understands this.

I know that last one because when the Behavioural Science revolution happened ~15 years ago, the world’s first governmental Nudge Unit was founded on the back of a framework called MINDSPACE. The full paper is here.

Here’s my tldr: there are nine robust ways to influence behaviour. Together they spell out the word mindspace. The ‘i’ stands for incentives. I thought David Pinsof’s recent post about them was pretty good. Here’s a selection of common ones:

The incentive we’re most used to is money. That’s why a lot of people do jobs they don’t like.

Another common incentive is approval. That’s partly why people are willing to do other things they don’t like.

Another familiar one, acceptance. That’s partly why people will do things that other people want them to do.

And a spicy one, status. Sometimes that’s why they’ll do things other’s don’t want them to do.

Why is that last one different? Because we can all (loosely) gain money, approval, and acceptance at the same time. But we can’t all gain status at the same time. What would that even mean?

My status is my relative standing within the group. If we’re a two person group, and we both increase our status, neither of us do. That’s also why if I gain status on my own, someone’s not going to be happy about it. That has to be the case, or it wouldn’t mean anything.

I hope you see what I’m getting at, and it’s not about status directly.

Each of us is partly motivated by the incentives in our environment, but sometimes, there isn’t enough to go round. This shouldn’t be news to you. Because you’ve been forced into these situations since you were born. These situations are what we call competitions.

i.e. Picture us at the starting line. Our behaviour over the next 100m is created by the incentive of the gold medal. But only one of us is getting it. So to prepare properly for this moment, thinking about your own incentive wouldn’t have been enough. You need to have understood my incentive too. If you didn’t consider that, and I did, then I would have trained harder than you, and you are getting smoked.

But if you did understand my incentive, then you are ready to go all out when the starting gun fires, because you know I’ll be doing the same.

Agreed so far? You may need to focus for this next bit.

Let me add another element. The gold medal still goes to the winner, and we both still want that more than anything. Bragging rights for life. But before the ref (is it a ref in sprinting?) fires that starting gun, he tells us there’s a second incentive.

‘If you finish within 1 second of each other, you both get £10’.

Hmm. Pretty generous right? No matter who ends up faster, we can work together to make sure that happens.

But as we each get set, the same thought enters both of our minds. “How can I know that they’re going to cooperate? If I slow down at the end to make sure we get the cash, and they take it as an easy chance to guarantee the gold, I’m then guaranteed to get nothing at all”.

So what choice do you make, to at least try make sure you don’t end up with nothing? You go full sprint. So do I. Maybe we still finish within a second of each other, but the point is this - Neither of us can afford to think about the money, as long as the incentive to win is greater, and there’s a threat of ending up with nothing. When we have separate interests, and have to guess at the other’s behaviour, the rational thing to do is act fully in your own.

If you understand that, and don’t think it’s my worst made-up scenario yet, then you understand Game Theory. You’ve maybe already heard it before with different characters, and under the name the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The point is that cooperation gets hurt by competition, and often, individuals have an incentive to act in a way that creates a sub-optimal outcome for the group (see also: nuclear arms races, damage to the environment, corporate collusion).

Now I want you to imagine that there’s more than two people in the world. Imagine there’s around 8 billion. Imagine that we all have various incentives to be responding to at the same time. Imagine that not everyone can win.

What sub-incentives can you not afford to care about if you want to ensure you don’t get screwed?

Let’s take a look.

“My dear, here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place. And if you wish to go anywhere you must run twice as fast as that.”

There are very few important essays.

Meditations on Moloch is an important essay.

In it, Scott Alexander draws on a wealth of examples of how systems that contain many entities often compel those entities to prioritise their own survival or success, even at the expense of the greater good. Individual interests can lead to societal costs, which means not getting screwed over is something to always be worried about.

Here’s an example I made up:

Let’s say there are just 100 different people that post Outfit of The Day (#ootd) style videos to TikTok, where they talk through what they’re wearing. They have a total potential audience of 1 million people that they share equally, because they all post in the same style. One day, one of them tries something new. They start their video in their underwear, and put their outfit on to a trending song. This hits viewers dopamine receptors more effectively, and they start to reach into everyone else’s share of the 1 million. So what does everyone else do? They also go with the underwear and music tactic, even if they think this is sacrificing what they liked about their original content. And they get their viewers back. Within 24 hours, order is restored and the 100 creators each have equal claims to the viewers. Except now, they all have to do more just to have the same position they had in the first place.

Here’s one of Scott’s scenarios:

“Large countries can spend anywhere from 5% to 30% of their budget on defense. In the absence of war – a condition which has mostly held for the past fifty years – all this does is sap money away from infrastructure, health, education, or economic growth. But any country that fails to spend enough money on defense risks being invaded by a neighboring country that did. Therefore, almost all countries try to spend some money on defense. From a god’s-eye-view, the best solution is world peace and no country having an army at all. From within the system, no country can unilaterally enforce that, so their best option is to keep on throwing their money into missiles that lie in silos unused.”

While the stakes vary quite a bit between those two, the problem is the same. And it’s this: When competition is a permanent threat, the coordination required to stop us having to break our backs to succeed is made impossible. Same as the two of us in the 100m race.

Scott again:

“In some competition optimizing for X, the opportunity arises to throw some other value under the bus for improved X. Those who take it prosper. Those who don’t take it die out. Eventually, everyone’s relative status is about the same as before, but everyone’s absolute status is worse than before.”

Remember how we noted near the beginning that systems often mean some people get what they want, and some people get screwed? And that sometimes, the system that is trying to please us creates an outcome that no one actually wants?

Scott gives a name to what it is that causes that: Moloch.

Moloch, originally named after a pagan God, is also the character described in Allen Ginsberg's poem "Howl," which itself uses the ancient deity as a metaphor for destructive forces in modern society:

“What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination?

Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable dollars! Children screaming under the stairways! Boys sobbing in armies! Old men weeping in the parks!

Moloch! Moloch! Nightmare of Moloch! Moloch the loveless! Mental Moloch! Moloch the heavy judger of men!

Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgment! Moloch the vast stone of war! Moloch the stunned governments!

Moloch whose mind is pure machinery!”

Scott:

“The implicit question is – if everyone hates the current system, who perpetuates it? And Ginsberg answers: ‘Moloch’.”

Moloch is the crippling force of coordination failure. The pressure to watch your own back that stops you from being able to see what you’re running toward. Keep an eye out and you’ll see him everywhere.

This isn’t speculation, it’s urgent. The reason this characterisation is useful is so you can remember one simple rule: when you see competition within a system, expect values to be ditched in order to optimise, and expect no one to be better off in the end. If you can spot this process then you can see Moloch, and you see the predicament of the actors involved. These aren’t bad people. They need help. They are slaves to the system that feeds them. They are slaves to Moloch.

And because their survival is on the line, they can’t just leave.

Two points of clarification before we continue:

(1) I know I started this essay implying that it’s silly to pin the causes of your problems on big powerful entities that you can’t do anything about. And now I’m saying some ancient God is the reason people have to be half naked to get attention on TikTok. This is a metaphor that shows how incentives and systems should be treated like living things. It doesn’t mean it makes sense to blame the metaphorical God. It’s still just us here.

(2) At this point you may be questioning how this essay is even meant to be about cultural homogenisation. If Moloch is such a pervasive force in any sort of societal outcome, and Moloch forces us to constantly be on our toes to move in the direction of the new thing, how could this also lead to a culture where there are no new things?

Great question, let’s keep digging.

Accepting the risk of potentially angering people, I’m going to try explain how culture develops in about ten sentences. This should feel a bit familiar, given that it’s governed the world around you for your whole life.

It goes like this: Groups of people communicate with each other to survive. They share ideas, practices and habits to start with, to give them the best chance at collectively succeeding. Then when civilisation starts to form and everyone’s more secure, they create and share music, dance, art, ideologies, whatever else to help decide how you should spend your relatively safe existence. These little pieces of information are what we call ‘memes’, and they leap from my brain to yours when I introduce one to you for the first time.

Over time, everyone starts talking to everyone in the group, and everyone throws a lot of memes at each other in the process. But no one has the storage to remember all the memes, nor could they have the time to communicate them all back. So given that memes all differ from each other, it is the ones that (for whatever reason) are more sticky that survive and earn that place in the collective (un)consciousness. These are the things you learn from one person, and decide to pass on to someone else. And just like a virus, those first few early wins predict that same meme is ready to take on the whole population. Hence, going ‘viral’.

Just like genes, memes can mutate and respond to pressure from the environment, all with the goal of self-replication. Some are better at this than others, and can spread faster. The consequence is that while the potential for different memes existing in an ecosystem is infinite, a finite few will take up a lot of the real estate. That’s probably for good reason, they must really resonate with people for that to happen. Those ideas must have really worked.

So we get a group of highly spreadable memes that dominate our conceptions of ways you could behave/things you could do/how you should think. Every sport you’ve played, type of live show you’ve seen, style of restaurant you’ve eaten at - they are a set of memes that have left a lot of less catchy ideas in the dust, and continue to have to fight off new ideas that people come up with. Some are going to get taken out when a new viral challenger comes along (e.g. video killing the radio star, baseball getting relegated from being America’s pastime, raving instead of ballroom dancing, Gen Z have never heard of AskJeeves).

Here’s a way to see the competition you’re consciously blinded from. In your life, you will see plenty of examples of arenas where the possibilities of how to act are theoretically endless, but we collectively agree that there are certain strategies that are most agreeable.

E.g. Cinema: There are more films released than you could ever watch, but they all fit into a select few genres. And within those, they probably all adhere to a handful of actual storytelling techniques. They might all have different composers doing the score, but they’re all operating within a narrow window of what we agree movie soundtracks should sound like.

This happens because they respect that they are in competition. It’s literally survival of the fittest. And the ongoing consequence of that competition is what we call ‘culture’.

Customs, behaviour, art, sports, religion, aesthetics, humour, lifestyles. These all have their league leaders, and they are battle hardened.

Take a moment to look around you. These are the memes that won. We should hand out gold medals. Someone somewhere was the first person to suggest screens should be shaped how the one you’re reading this on now is shaped. That idea caught on enough that everyone now thinks that this is simply how it should be.

The playlist you have on in the background is filled with songs that resonated with enough people to pick them over other songs you’ve never heard of, which meant they landed in your algorithm, and you get to keep that process going when you post them on your story.

Culture is competition. It has winners and losers, and the winning prize is a place in consciousness. We just can’t see it because the losers must live outside of your memory or else they wouldn’t be losers.

So, how do you win?

Combining our observations of how memes compete and Molochian dynamics of competition, the lesson is this: One meme is going to work out an advantage, and when they do, the rest of the memes will have to follow suit, or they’re left for dead. This process invariably means they all have to shed parts of their makeup to stay afloat. They can all survive this round, but they’ll all be a bit worse off.

And then another meme works out another advantage. And everyone has to lose a second value. Maybe some don’t want to lose that value, maybe they hold it really dearly. But you’ll never know about those ones. They’ll never reach your consciousness. Because they’ve lost the memetic competition.

And guess what also happens: The closer the memes get to optimised virality, and the more they have to react to each other’s strategies to ensure their own self-replication, the more their individual makeup has to begin to look the same. Anything else is a risk. (for an example in a literal competition, have you ever seen what analytics did to shot locations in basketball?)

So the question is: what are the characteristics of an optimised meme?

When the brain has 100 memes thrown at it, which has the best chance of landing? What is the stickiest? What does the brain like to see in cultural information?

Here’s a real behavioural biology experiment that happened in the ‘70s:

“Tones of two different frequencies were played to two sets of fertile chicken eggs. When the hatched chicks were then tested for their preference for the tones, the chicks in each set consistently chose the tone that was played to them prenatally.”

I came across it in something a bit more modern and mainstream, the work of social psychologist Robert Zajonc. You can look for yourself, here.

The chicks in this experiment showed a preference for something that was familiar. Now, they could have associated it with something more than that, some kind of incentive. But all their brains knew for sure was that it was familiar. The rest would just be hope. I might still be giving chickens too much credit here, not my bag.

Anyway, Zajonc pulls on this for a reason. Because it’s analogous to what is a robust and reliable effect (r = 0.26 if you swing that way) in human behaviour too: the mere-exposure effect. Check the definition:

‘People tend to develop liking or disliking for things merely because they are familiar with them.’

This works in some pretty wide contexts:

The more you interact with someone, the more you tend to like them

Repeated viewing of the same artwork increases liking of it

Repeated exposure to unfamiliar music leads to more positive ratings over time (including in the Eurovision song contest specifically)

Familiarity breeds liking. Advertisers get this. Pop music producers get this. Party Campaign HQ gets this.

Now, don’t get ahead of yourself. I know this solves a big part of our problem already. But a couple of extra details matter. A meta-analysis of the whole area found that the effect is strongest when unfamiliar stimuli are also presented briefly, and that mere-exposure typically reaches its maximum effect within 10–20 presentations.

Familiar and unfamiliar stimuli getting quickly presented one after the each other, with 10-20 representations being required for the familiar to really take hold. Does that, by any chance, remind you of anything …

When delving into explanations of how the mere-exposure effect works cognitively, Zajonc’s mentions that repeatedly seeing something makes you like it more, especially if you don't consciously realise that it’s happening.

To quote: “In fact, exposure effects are more pronounced when obtained under subliminal conditions than when subjects are aware of the repeated exposures.”

Affect doesn’t need cognition to occur. You can express preferences without consciously realising you even have those preferences. This is the same point I landed on when I said that motivation precedes cognition previously.

If you use TikTok, I predict that you are living proof of this idea. Here’s a test: have you ever scrolled your FYP, come to a video, and hit like before you have even consciously perceived what you are watching? I bet you have, and I bet it turned it out to be a meme you’ve seen approximately 10-20 times before.

Let me make another guess about you. You ever finished a 20 minute TikTok session and not been able to recount a thing you saw? Like your brain didn’t need you to be conscious in order to get the dopamine top-up it was after? I reckon you know what I mean. And that’s crucial. The effect wouldn’t be as strong otherwise.

There’s another point here that I’m scared of not getting across: People unconsciously liking stuff they are familiar with on TikTok, and therefore increasing the chance they see them again, does not necessarily mean that TikTok leverage this effect to shape behaviour or preferences and you’re thus getting screwed out of more meaningful content. This would be a weak inference, and a lame excuse for your own behaviour.

In fact, here’s a confident prediction: TikTok could go non-profit and cut all ads tomorrow, and this would still happen. TikTok could even try harder to diversify the content on your FYP, and this would still happen. TikTok could not have any incentive to care how long you spend on the app, and this would still happen.

Because the like is still the only way to express a want, and the system is trying to add our wants together. And your brain likes what it likes, even if we don’t like the aggregate outcome.

The subliminal nature of familiarity is approximately where Zajonc’s analysis ends. But some philosophical speculation remains. It seems we are unconsciously motivated to like the familiar, but why?

Here’s my take, that is built on the argument I set out here:

Once you are fed and safe, the real human goal is certainty. Certainty in yourself. Certainty in your environment. Certainty in what is going on. When you are thrown into the world, you are not told who you are or what to do with yourself. So we get to building our own answers to those questions. Obviously, they will forever be unanswerable, but that doesn’t mean they have to seem that way to us. In fact, we need to think we’ve answered them in order to do anything at all with our lives. It all needs to mean something.

Familiar things feed that goal because they have already been factored into to our representations of what an inherently uncertain universe consists of. They fit the model, and conform to expectation. Novel things don’t, which means they are scary because the unfamiliar reminds us that nothing is certain. And that is the abyss from a psychological perspective.

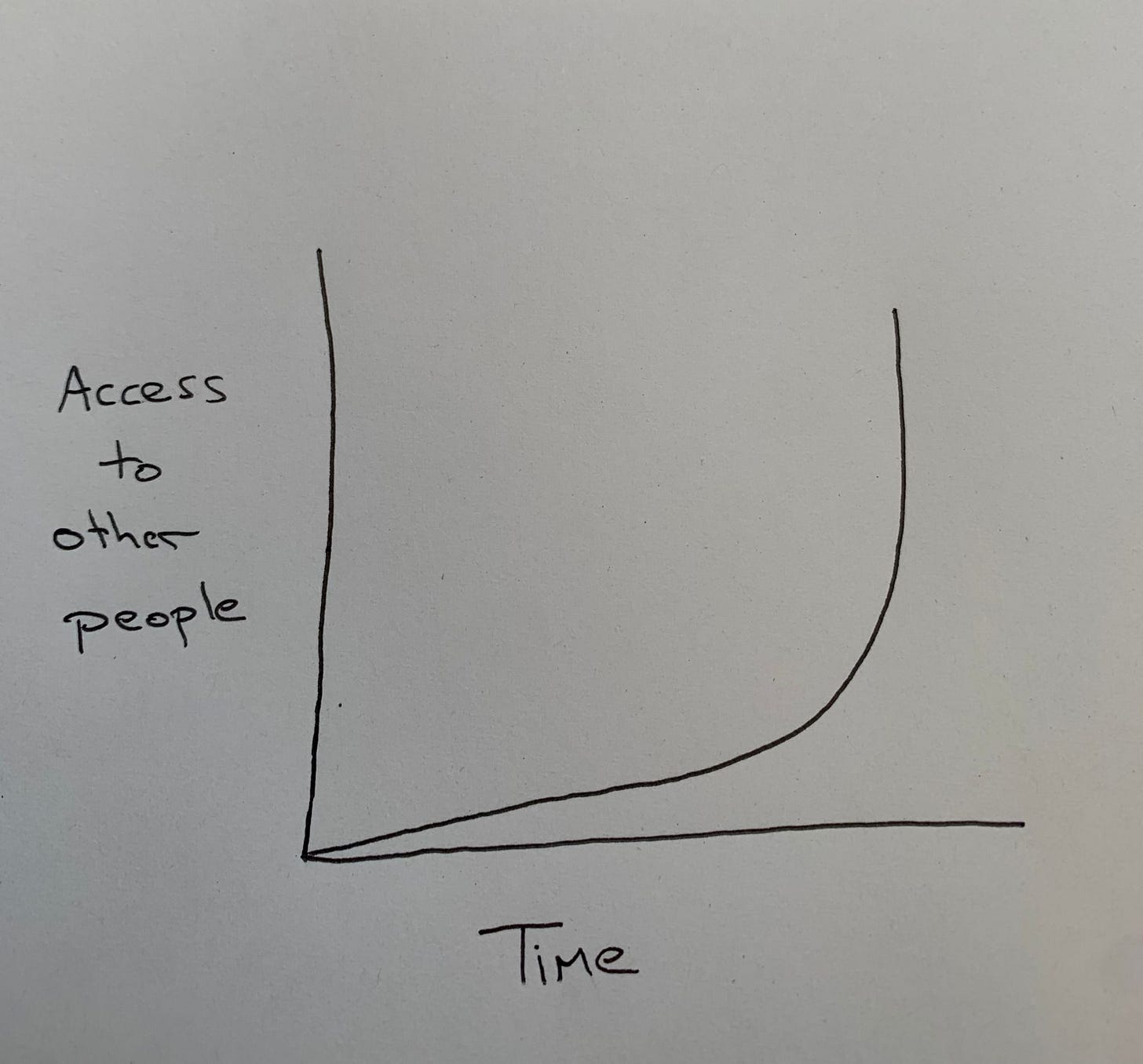

Two highly detailed graphs for you:

The shapes of the curves matter a lot psychologically. The first post on this substack was about this. Things that change suddenly tend not to get on well with System 1 thinking, and even System 2 takes some time to get there.

The one force that has grown at a super-linear rate for the last century, and has caused plenty of other things to grow or decay super-linearly in the process, is technology. A prime outcome of this, and the internet specifically, is that your ability to exchange information with people looks a bit like the first graph.

This affects our cultural equation dramatically. In a pre-historic 50 person society, certain memes still rise to the top to create culture, but they haven’t had to beat all that much. They can be rough around the edges, just as long as they have some sticky property. It’s a finite game.

What technology does is make this game infinite very quickly. Which simultaneously makes the competitive stakes very high, and drops the barriers to entry to zero. Anything that’s not a well-oiled, easy to reproduce meme will not do. Eventually, they have to be all sticky property. So what can’t survive? Things like detail, variety, novelty.

What’s interesting is that these are the things critics claim to be really important to a healthy culture, but as I’ve tried to show, culture does not care about them at all. Novelty’s days were numbered from the day the first two homo sapiens invented words. Same for detail. There’s a reason why doors and windows used to be fancier.

Every technology brings us closer together, and reduces the total number of memetic competitions. It’s the equivalent of converting of 20 games happening in 20 stadiums with 4,000 seats, to having one game with 80,000. In the latter case, the standard you need to be at to be a player is higher, and the pressure to succeed feels much heavier too.

And the bigger the competition, the less capacity memes have to care about anything other than familiarity.

Cultural variation isn’t the outcome of the system, it is proof of resistance within the system. Newer technology hasn’t created a new system that has a different goal to the old one, it has just pulled all of the resistance out of it. To the system, this is optimisation. TikTok seamlessly transitions between memes with no effort on your account, which also means you face no resistance in your ability to find comfort and reduce uncertainty.

Much smarter people than me already laid this out decades ago:

This is the Culture with a capital C that Iain Banks conceptualised. His fictional society represented the peak of cultural evolution, where technology has resolved fundamental societal challenges, leading to a scenario where culture is no longer functionally constrained but is instead purely memetic. In Banks' vision, technological advances have freed culture from material necessities, enabling a society dominated by self-replicating memes — ideas and cultural elements that propagate themselves purely based on their appeal to human sensibilities and tastes. The Culture, thus, emerges as the ultimate expression of this memetic triumph.

This is also essentially the point of what Adorno laid out with his idea of the culture industry. According to Adorno, the culture industry commodifies and standardises cultural products, leading to a mass society where cultural consumption is driven by recognition rather than critical engagement or genuine appreciation. In this framework, the familiarity of a cultural product often dictates its acceptance.

But I’m writing this essay because there is still a key difference.

Because Adorno looked at that version of mass culture and saw profit.

I looked at it and saw Moloch.

Aside: this doesn’t mean you have to take the optimal strategy, it just depends on your incentives. Do things your way if its makes your soul burn with a hotter flame, but don’t expect the likes to pour in. Take it from the guy writing 10,000 word essays about memetics in 2024. This is the thing I wanted to make. But if I didn’t have a steady income already? This is getting delivered in 30 second spurts with subway surfers playing underneath. Topless, if you really want me to.

I mentioned at the beginning that you can’t just leave this situation. I really mean that. No amount of counter-signalling, echo-chambering or self-expression does the job. That’s still playing the game. Kyle Chayka’s book tells me a month-long algorithm cleanse is the best way to build a healthy relationship with the internet, but what is most important about that strategy is that it *still emphasises that you need to have a relationship with the internet*.

Leaving would look more like packing your things and heading for the outback, living off the fat of the land and not paying a phone bill. But this won’t work either. Maybe it would have a thousand years ago, but not in 2024. Because it turns out someone else owns that strip of grass, you’re getting charged for rough sleeping, and this police officer doesn’t care what you’ve opted out of.

That’s right, you’re stuck.

One other thing I agree with Scott Alexander on is that this is pretty much all you need to formulate support for a universal basic income. You have to play the game everyone else has designed, which has some obvious flaws, and you cannot go anywhere else. If you were born somewhere in the first 80% of our time as a species you wouldn’t have to deal with this. But you were born now, post civilisation, and today it takes a lot of time and effort to really count as a human in the eyes of the system. Very sadly, some people never even get there. So whose responsibility is it to save them from the system we created? The system itself won’t because it has a different agenda, and if you’re hoping for some other kind of invisible hand then I’ll put that under the bucket of ‘praying’. The games already started, it’s only right we give new players the right gear to take part.

Ok that got a bit intense, back to TikTok and coffeeshops or whatever.

Let’s map out what I’m saying. The so-called flattening of culture in the age of algorithm is well evidenced. I propose that this is driven by memetic processes whereby the things that are most recognisable reach the top, which leaves little room for anything new or different. This is an arm of what I/we call the system, which is the aggregate of our collective wants. That’s why I think we are all complicit.

But people want all kinds of conflicting stuff, so what makes the cut for these collective wants? What do we sacrifice and what survives?

Start by asking yourself what you want out of your existence. I bet you can deliver a beautiful answer. Look, I know I come across cynical in my writing at times, but when you list off all of those different types of pleasure, purpose and happiness, I completely believe you. I want those things for you too.

The thing is though, it’s not up to me. And it’s not up to you either. Everyone wants some version of these things, but when we all gather to meet these goals at the same time, a competition begins. When that happens, it’s up to Moloch.

So when all of these complicated wants and desires meet in the cultural arena, what is the one thing that has to survive the process in order to avoid the abyss?

My answer to that is the very first psychological problem we face when we’re thrown into the world. And that problem is: who am I?

“I wonder if I've been changed in the night. Let me think. Was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next question is 'Who in the world am I?' Ah, that's the great puzzle!”

For me there are two issues with the discourse around the cultural stasis problem, that will combine to prevent anyone from ever actually solving it.

I. The insistence that someone/something else is doing this to us.

II. The incomplete ideas of cultural stasis and algorithms preventing people from doing the things they really want.

Something that’s kind of funny is that it seems most people jump to blame number one on capitalism, where it doesn’t necessarily matter. What this actually stops them from seeing is that capitalism is much more relevant to number two.

Because I hate to break it to you, but when you commit yourself to an algorithm cleanse as part of your pursuit of what you picture as your ideal lifestyle, where is that picture coming from? Does anyone you know have a life like that? Did it come to you in some repressed dream? Or was it just a Patagonia ad?

There’s a crucial distinction to be made here. Because most people can accept that the system tells you what to want. But the more important process happens first, when the system teaches you what it is to desire something in the first place.

Speaking to Kyle Chayka about cultural flattening, I heard Ezra Klein mention he’s finding it harder than ever to be an individual. Which is funny, because isn’t this the most individual society has ever been? Doesn’t technology enable individualism always? So what gives? Where’d all the Main Character Energy go?

What you most often see if an explanation that the drive to individualism is real, but it’s the algorithm that takes it off track. Reading all of the above, you can see there’s the beginning of some sense of that.

But guess what anti-algorithmers are all eventually destined to realise? Locking your mental doors to the algorithm doesn’t make it go away. Because it can’t go away. You define who you are by your place within it.

And you can’t just leave.

And so I present to you the grand irony of culture of the 21st century. From the same system who brought to you ‘Goods That People Buy But Wish Did Not Exist’, I give you: ‘The Main Characters Who Became NPCs’.

It’s one hell of a punchline. But I guess it’s nothing we didn’t know already. The system can do its best to optimise itself towards you, and you can have the things you want for yourself, but it’s the system that’s feeding that’s helping you build those ideas in the first place. In other words, when we all have no flaws, we’ll all look the same. So will our coffee-shops. So will our cars.

Algorithms flatten culture because to the system, this is optimisation. It thinks it is serving us but that is how we’ve told it to serve us. And if you think upgrading to an AI-based meme ecosystem reverses this, I’m not convinced you’ve been paying attention.

Is that a problem? That requires many more words. But let’s say you do think it’s a problem.

Who’s got the tools to aim it in the right direction? Who’s responsibility is it to save us?

Don’t let the ego play one final trick.

Don’t just hope that there in inevitably some new era of the digital where the joy returns because that’s the ending that makes sense. Don’t think there’s someone pressing this great stasis upon you, that the New York Times is fighting in your behalf.

Because it’s not Sam Altman. It’s not Google/TikTok/Elon Musk. It’s not Joe Biden or Rishi Sunak. It’s not Wall Street, and it’s not Rupert Murdoch.

It’s the system that they are all a part of. And as I’ve tried to explain, my friends, that includes you.

And you can’t just leave.

“Begin at the beginning," the King said, very gravely, "and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

Short comment:

This reminded me a lot of Lewontin's Paradox of Variation: the fact that genetic diversity does not increase with population size as expected. From my ignorance, I suspect the mechanisms are similar.

Long comment:

Yesterday I read "She Said I Want Something That I Want" [1] and was very impressed by the content. There was a link to this one and, again, it was an awesome read. Both posts are probably not life-changing but they sure are mental-model-changing.

[1] Which was linked to in "The Artification of Culture" by Simon de la Rouviere.

I came to the comments section expecting to see dozens of comments... and not a single one. Ok, you were right that "writing 10,000 word essays about memetics in 2024" is not the best way to get views. Maybe it's better that way because the forces described in this post do not apply to this blog :).

I have to say that in my case you are preaching to the choir. I opted out of algorithmic content years ago and now only use RSS and sites with simple chronological sorting. And regarding this:

> The system is not ‘them’, it is ‘us’. And you can’t just leave.

> ‘The Main Characters Who Became NPCs’

In my experience, if you're lucky ($lucky$) enough, it's possible to leave... but only up to a point, and you'll have to give up a LOT. As you say later, "you have to play the game everyone else has designed", but you can choose (almost) not play at all. I like to think I've avoided the NPC phase by not playing.

Anyway, thank you very much for sharing your writing.

"If you're reading it, it's for you."