She Said I Want Something That I Want

ceci n'est pas une 'hangout epidemic'

‘Even facts become fictions without adequate ways of seeing the facts’

(warning: long, and contains Lacan)

Saw a new article last week. ‘Why Americans Suddenly Stopped Hanging Out’ in The Atlantic. I’m a fan of Derek Thompson, but I think this article accidentally explains a lot more than he intended it to. It explains a lot of it just by existing.

Thompson takes us from mid-90’s Bowling Alone to 2020’s scrolling alone, citing numbers from the annual American Time Use survey along the way. We get to see that:

From 2003 to 2022, American men reduced their average hours of face-to-face socializing by about 30 percent. For unmarried Americans, the decline was even bigger—more than 35 percent. For teenagers, it was more than 45 percent. In short, there is no statistical record of any other period in U.S. history when people have spent more time on their own.

Teens are dating less, playing fewer youth sports, spending less time with their friends, and making fewer friends to begin with. In the late 1970s, more than half of 12th graders got together with their buddies almost every day. By 2017, only 28 percent did.

Which is correlated with:

Teenage depression and hopelessness are setting new annual records every year. The share of young people who say they have a close friend has plummeted. Americans have been so depressed about the state of the nation for so many consecutive years that by 2023, NBC pollsters said, “We have never before seen this level of sustained pessimism in the 30-year-plus history of the poll.”

This made me think of a second article I read last week. ‘In 2024, everyone is yearning – but what for?’ in Dazed.

This one starts by being about One Day on Netflix to get you in the mood for introspection, before telling you what the real idea is i.e. desire has changed:

Social media is now filled with people “yearning on main”, being hauled to “the emergency room with third degree yearns” or sharing their “terminal” and “catastrophic” yearning diagnoses. On the more abstract end of the scale, there’s ‘yearnposting’, where people post text and image slideshows with a vague, mournful vibe (like ‘the sun is going to return’ over a picture of a sourdough loaf). Google Trends paints an even stranger picture: people searching for both ‘yearning’ and ‘longing’ have been climbing for the last two years, with a spike in the last month.

It goes on to suggest that this yearning is a reaction to modern disillusionments: economic stagnation, social isolation exacerbated by the pandemic, and a collective nostalgia for a seemingly more hopeful past. Before adding the quote: “We’re just in this really passive time. We’re like the palliative generation; there’s so many things that are out of our control, and we’re just kind of ‘hands up’ about it”.

Suddenly, after reading a few more lines, we realise this is the same article as the one in The Atlantic:

Disillusionment is also not a new phenomenon, but it has felt more potent in the last few years. It almost feels too obvious to mention social media and smartphone dependency, but they have both had an undeniable effect on the human personality. Aside from being terrible for our mental health, we know they can create a false sense of connection: four-fifths of Gen Z now report feeling lonely, having swapped IRL social contact – with all its nonverbal cues and intimate physicality – for an illusion of closeness and belonging.

The two websites/magazines/whatever you call this type of media are just going about it in different ways.

Once The Atlantic article wraps up it’s evidence that something is going on with how often people are hanging out, it follows up with suggestions why. Here they are, with the word count slightly taken down:

What are the root causes of the great American introversion?

The first explanation is so obvious that it scarcely needs mentioning. Americans are spending less time with other people because they’re spending more time with their screens. The evidence that young people have replaced friend time with phone time is strong. Even more telling, the groups with the largest increase in phone use, such as liberal 12th-grade girls, also saw the largest declines in hanging out with friends, strongly suggesting a direct relationship.

The second explanation is that people are hanging out less because we’re all so damn busy. As The New York Times’ Jessica Gross notes, people in their 30s and 40s have less leisure time than they did two decades ago.

A third explanation for America’s cascading social mojo is the Putnam theory described in Bowling Alone: The rise of aloneness is a part of the erosion of America’s social infrastructure. America is suffering a kind of ritual recession, with fewer community-based routines and more entertainment for individuals and the aloneness that they choose.

If you can read that and not see what’s wrong, then you have fallen into the same trap as the writer. And I don’t mean what’s wrong with society, I mean what’s wrong with the answer.

An initial reason to suggest this is the wrong answer is because, well … none of this makes the slightest bit of sense. Hone right in what both Dazed and The Atlantic are saying. Both begin with the starting point of IRL social connections being down.

The Atlantic pivots to the causes and identifies (1) more time on screens (2) more time on work and (3) less time in community. Dazed pivots to the consequences and sees disillusionment and yearning.

So we have people that are hanging out less because … they are hanging out less. Which has made them full of yearning as a result of them being so disillusioned. Hang on, what do yearning and disillusioned mean again? We’re so full of desire because we’re so apathetic and passive? Is this an article or a riddle? How is everyone so full of longing yet no one wants to date each other?

Don’t worry about it too much, because there’s no meaningful answer there. The important thing is this: disconnection seems to be very real and very current. Something has gone wrong. Both authors are so close to seeing why.

Here’s a big hint from the Dazed piece: “Google Trends paints an even stranger picture: people searching for both ‘yearning’ and ‘longing’ have been climbing for the last two years.”

Think about it like this: when you’re longing for something in life, and you take out your phone, wouldn’t you search … for the thing your longing for? Better yet, wouldn’t you do something about getting the thing you want? Like, if you were hungry, and there was no food in the house you could either (a) walk to the supermarket or (b) open Uber Eats. Or, like those people on Google trends, do you just search the word ‘hunger’?

Now, can you see that if that was the behaviour, it would be a mistake to take that and write an article asking ‘Why are people so hungry?’ Perhaps, that might just suggest your problem is something else.

Similarly, if you were hungry again the next day. And you have the time and money you need to get food from the supermarket across the street. And you don’t. You choose to do something else. Everyone on the street does the same, and the supermarket is forced to close. Can you see then why the wrong question is ‘why is there a supermarket access crisis?’

What you need to understand is that in both cases, the authors had a chance to look at people, and instead saw society. For that reason, they took some good data points, but used them to form the wrong questions, and thus could only supply the wrong answers. And there’s no correcting that course once the journey has begun. So to get things right, we’re going to have go all the way back to the very start.

The Atlantic asks ‘why did Americans stop hanging out?’

Dazed ask ‘what is everyone yearning for?’

Both assure us that finding an answer is urgent. But to learn how they have both ended up asking the wrong question, you’re going to need to unlearn something else.

You ever think about how shit you are at drawing?

OK, shit is relative. Put it this way instead: you ever notice how you’re about as good at drawing as a literal child? Most other skills in life, you wipe the floor with anyone under 12 (I hope). But if I challenge you to draw, say, an elephant, and give the same challenge to a random 9 year-old. How confident are you a third party is going to be able to tell which artist has a developed prefrontal cortex?

If you agree with the suggestion, the next question is why. Why do you go from scribbles when you first pick up a crayon, to something resembling shapes, to stick figures depicted in scenes and then … nothing more? I bet at least one person reading this did one of those big S drawings in a schoolbook and never reached those heights again.

You may be quick to suggest that you’re shit at drawing because you never draw. If you drew more, you’d quickly start seeing improvements. Your hand-brain connection would be getting sharper, or something.

Well, I don’t buy it. I’ll show you why.

To be more precise, you’re gonna get shown by a book from the 70’s.

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards is the most popular drawing instruction book ever (credit TLP for the tip). But it’s not based on insights from artists. It’s based on insights from neuroscience. And it really works.

It tells us three really important things:

Why you’re shit at drawing

How to get better at drawing

A secret third thing

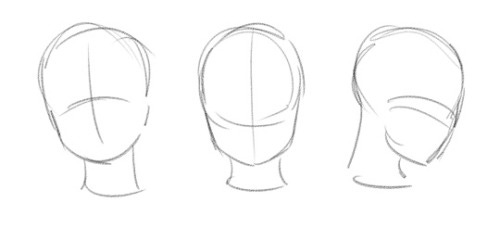

To understand the first one, observe how you go about drawing. Let’s say the task is drawing a person. Someone you really know. Doing something you’ve seen them do a thousand times. Your partner making a cup of coffee, for example.

When your pen hits the paper, what happens?

You probably start with a vaguely contoured head, draped by straightlined hair. Next comes the body. Of course they are stood bolt upright. Torso facing straight at you yet their feet are flat to the side. And they’re just about looking at the coffee that’s already made. Do their arms even bend or do they look like those big pringle cans? Do you think the legs are proportionally tall? What about where the cleft beneath their nose starts to blend into top lip?

Yeah I thought that last one was a stretch.

OK, so what happened? Why have you produced something I’d have to pretend to be impressed by if a 5 year old did it?

The answer is that when you started to create your partner, you didn’t take any time to visualise the scene as you’ve seen it before. You instead take a shortcut and asked yourself, what are the rules of the human body?

Well, that’s simple. They have a head, with hair on it. That sits on the body, which has four appendages coming out of it. And we’re done. You’ve taken the rules of a human and then presented them as a human. As it turns out, these are different things.

More specifically, you’ve taken the parts of the body that symbolise what a human is constructed of, and fit them together after the fact.

But let’s say you accept that, and promise to try harder next time. OK, let’s see what you got. Go again. Close your eyes and imagine the same scene in as vivid detail as you can. And then make your pen do that.

Notice the problem? You can’t imagine the scene in that detail. Even though you’ve spent a lot of time gazing at it in your life.

Follow through with the drawing, and the same things happen again. Feet bigger than anyone’s have ever been, arms in a position they’ve never been in before, and a facial expression that may be indicative of some medical problem.

The symbols took over your hand again.

But they led you astray. They sold you the line ‘this is what a person looks like’, made you feel like you did in fact know what a person looks like, and left you with something nowhere near.

And this is why the best drawing book in the world is a neuroscience book. Because when you try to draw something you’ve seen before, that’s not the image your brain supplies. Because it doesn’t have the goods. It can’t even give you the right shape. But it tells you it is the right shape.

So how are you going to blame your hand? What chance did it have. It got swindled.

Edwards describes ‘the tyranny of the symbol system’ as the force that causes us to reproduce symbols over what we actually see. Which means you aren’t a bad drawer because you can’t move your hand properly. You’re a bad drawer because you can’t see properly.

So what you actually need to practice isn’t drawing. It’s how to perceive the things happening in front of you, without converting them to symbols. Then the drawing comes naturally.

How do we perceive better? This is the second big thing the book teaches us.

Your problem is that your brain is too efficient at taking shortcuts. It doesn’t need consciousness to be involved. When it’s time to draw your partners eyes, even if they are sat across from you, you look at them, your brain realises they are eyes, and sifts them under the abstract concept of ‘Eye’. You don’t have capacity to keep an image of every eye you’ve seen, that’s inefficient processing. So just this one defining abstract eye remains. And it ends up on your paper without you realising the sleight of hand your brain has performed.

So to counteract this, you need to do things that disrupt your own fluency of perception. You have to put something in the way to stop your own shortcuts from working their magic. You need to stop your brain from realising that what you’re looking at can be abstracted to a broader concept. Then you get to see what’s actually in front of you.

In a sentence: to learn how to draw, you need to unlearn how you perceive.

Two quick ways that actually work, if you want to prove to yourself that you’re a much better artist than you thought:

Find a picture you want to replicate. Before you start drawing, turn it upside down. Draw it inverted. You’ll realise how much slower you have to go. You’ll realise you have no rules to automatically follow. You’ll realise how much attention you have to pay to what’s in front of you.

Put the original picture the right way up again. But this time don’t draw the object itself. This time focus on what’s not the object. Colour in the empty space. That’s something with a shape your brain has no shortcut for. Here’s a drawing of the grass in a garden, that the artist could only catch glimpses of in some places. Can you see what they ended up drawing as a by-product? What would it have looked like if they had tried to draw the chair?

The secret third thing this teaches us, and which happens to be one of the biggest lessons you can take from psychoanalysis, is that this is the same process your brain development followed for pretty much everything else.

At some point your brain worked out a shortcut that helped organise a lot of similar things into one unified concept. And then threw away the evidence. You have the symbols, but not the pieces you used to build them. And these concepts absorb and transform every new thing your brain consumes from that point onward.

Which means that the path from perception to production is mediated by symbols. Always. Your brain can only process so much information, and this was the evolutionary efficient way to keep that information to everything you need to know. So you can never really recount or reproduce anything, or anyone, properly. Sorry to break it you like this.

OK. So why focus on drawing (he asks, setting up an essay that is clearly at this point not about drawing at all)? Drawing happens to work as an example because it’s the type of symbolism you can see. Which means the faultiness is on display. It’s not hard to tell when a sketch is pretty far from being realistic.

But what about symbolism that isn’t visible, how do you tell then? I don’t mean whether you can tell something is a symbol, as it is almost certainly is. I mean whether it’s any good as a representation of what you’re trying to get at.

Let’s turn our attention to the most common type of invisible symbolism.

What’s something else you picked up as a child that helped your brain organise the world into categories, make everything comprehensible without being overwhelming, and give you rules to how to recount things?

Like, when you can’t show someone something that happened to you, how do you get across the idea?

It’s something you might call: language.

Words are big business. Hence, magazines like The Atlantic and Dazed exist. Also, hence, substack.

But words aren’t physical things. They aren’t real. They’re generalisations. The word dog can be used to describe hundreds of things that look completely different. What about the word ‘red’?

Then you have words that aren’t even trying to describe physical things. ‘Freedom?’ ‘Happiness?’ ‘Capitalism?’ ‘Art?’

Ok, they have definitions. Sure. But guess what definitions are made up of?

Words are symbols. They are ideas. They mediate what we see in the world, and convert it into something reproducible. Something that you can explain to a friend over coffee without having to agonise over every blade of grass in the story of how you broke up with your ex in a local park.

But when your brain interprets everything through them, you are under the tyranny of symbols again. When you walked past that local park, you didn’t even see all the blades of grass. Not properly, anyway. You saw ‘park’. Your brain perceived ‘park’.

So, the brain prefers abstract ideas for processing reasons and, again, words are big business. How do you use them right?

The goal of a website like The Atlantic is to take some new information, and explain it to the reader. Explain it using words they know. Give it context through things they know about already. Concepts they know already. You can’t just show them the thing, that leaves too much to interpretation, right? Even if you did, they’d just do the same thing to themselves.

I assume you see the problem.

You require a journalist who can perceive perfectly what is happening, without their brain getting their first, and then put that into words in the most literal way possible.

This is obviously impossible.

But I’ll say this next part a million times if I have to. The consequence of reliance on symbols is not at the end of this process, where you’re trying to express yourself. The consequence is paid at the start, where you cannot perceive the thing in front of you without seeing it through something symbolic.

The issue isn’t with your hand, it is with your eyes.

Your eyes are convinced they saw something, and when you produce the words to explain it later on, there is no way for anyone, especially you, to know how well they are representing it.

This time, there is no childlike drawing to make fun of.

But if there was a childlike drawing, how do we spot the reliance of symbols to perceive reality? We see it through the rules the artist followed. The abstracted conventions. 2 chunky hands, 2 straight legs, one L-shaped nose etc.

So what’s the equivalent in language? How can you see if someone’s relying on abstract concepts to look at things, rather than forcing their eyes to pay attention?

Luckily, you can spot it. Sort of. I’ll show you how.

Let’s look at a quote from the Atlantic again. This one attempts to explain why hanging out has stopped. Except this time I’m going to edit out the symbolic language.

You need to take out anything the author had heard of before this topic even came up.

When you take out all of the words that are filler phrases or words that could be placed in literally any op-ed about the state of culture/society, and thus aren’t direct expressions of what the author can see in the current topic, what remains?

“

One can imaginea similar framework to explain the deterioration of America’s social fitness.We come into this world craving the presence of others. But a few modern trends—a sprawling built environment, the decline of church,social mobility that moves people away from friends and family—spread us out as adultsin a way that invites disconnection. Meanwhile, as anevolutionary hangover from a more dangerous world, we are exquisitelyengineered to pay attention to spectacle and catastrophe. Butscreens have replaced a chunk of our physical-world experiencewith a digital simulacrum that hasenough spectacle and catastrophe to capture hours of our greedy attention.These devices so absorb usthat it’s very difficult toengage with them and be present with other people.”

Can you see what’s in front of you now? This is drawing a stickman and referring to it as a human. It’s following the rules of what an answer should look like, and it could even be correct, but you aren’t using your eyes to come up with it. You’re using what you’ve learned an answer should look like. There’s barely anything left over.

Let’s try it with the Dazed article too.

So why are we yearning so much now?

Anecdotally, there seems to bean unshakeable sense that something has been stolen from us. A lot of friends in their late twenties and thirties, worn down by15 years of wage stagnation and rising cost of living, seem to be isolating themselves,growing morerisk-averseand inclined to settle. Friends in their early twenties,after having two years of their youth stolen by the pandemic, complain about struggling to let their guard down and form meaningful connections. What unifies the two is a kind ofdeathly boredom and disillusionment with modern life– a yearning for something in the future to feel optimistic about. “Yearnposting uses the internet to mimic what we feel like we’re missing in real life,”explains Maia Wyman, video essayist and host ofRehash, a podcast about social media phenomenons. “We’ve begun to feel like these kinds of emotions aren’t available to us, so we’re almost trying to use the internet to recreate them: here, feel something with this video,because you’re probably not capable of it [in the real world] right now.”

Look, my point is not necessarily that wage stagnation and cost of living are irrelevant, and should be cut. It’s that even if they were irrelevant, they would still be mentioned in this article. Because these are the the types of things that get mentioned in these types of articles. No one has ever looked at an asexual teenager and literally seen the cost of living, but this writer managed to.

And now we have to guess if that was a good shortcut or not.

So we can agree that the two articles are cases of people being reliant on symbols. As are most articles in the genre. Nothing personal, guys. Because of that, they are bad at drawing. We don’t know if what they are seeing is accurate.

So, how do we help them see better, and start to understand where modern problems of disconnection really come from? What would those writers see if they could open their eyes properly?

The first thing I said in this post was that The Atlantic explained a lot of it just by existing. It’s time to show you what I mean.

What you might already realise is that there is a grand irony of people not being able to see past symbolic language in tackling modern problems of alienation. Symbolism and representation creates a distance from the real experience, right? So that’s how you end up quite detached from the root cause of the issue you care about.

But consider when, like in this case, the issue actually happens to be that people have ended up too detached from each other. What creates that distance? Just as when writers look at time use data and can’t get their brains to see it properly, why do people increasingly struggle to look at their fellow humans and see them properly too?

Let’s do a case study:

If you’re into modern psychology, I implore you to spend more time in anonymous spaces online. It’s amazing how much people will give away when you turn down the social cost. For the various people planning to pen long reads on romance and dating this year, I advise starting on reddit.

Here’s a real story from a guy on r/dating_advice, titled: “Girl ghosted me out of nowhere. I thought we had an amazing time.”

Hi I’m a 28 (m) that went on two dates with a 28 (f). We met on a dating app and started talking for about a week before we met up. So we met up for mini golf, went to the arcade, and had dinner for our first date. I did my best to make it a positive experience, was a gentleman, and paid for the date. We got to know each other and ended with a kiss. She texted me saying she got home saying she had a good time and even said I was a good kisser. I told her that I wanted to set up a second date in a few days because I was going on vacation soon. So we texted back and forth for a bit and set up a second date before I went on vacation. I had these funny dating flashcards setup as a way to break the ice too during our date. Even the bartender said that it was an amazing date idea that he wish he did with his wife. So we talked about a 3-4 hours before we went home. This time she payed for it but I offered that I was going to pay. But she said that I payed for everything the first date and that she wanted to be fair. So I didn’t fight it.

2 days after our second date, I noticed she didn’t respond to my text as much and only like texted me toward the end of the night. “hey, (name) I hope you didn’t forget about me haha! I just wanted to make sure you’re doing okay”. As of today, I didn’t get a response for that message either. So I’m just confused to what happened? Was it my Instagram? I don’t really post a lot nor do I have like crazy pictures. Mostly me just doing my hobbies like golfing, painting, cooking etc. and there’s not much to look at cause again I’m not a social media person. Was it the date? Did she lie? Was is it because she payed the second date? I asked my friends and they said that they don’t understand either and that the girl was not worth my time because it was messed up to do something like that. They were like she mislead you and you don’t want a girl like that. Any thoughts? What should I do?

So his big question is: “Why did this girl ghost me, when I thought we had an amazing time?”

Given we have no way to get her perspective, the best question I can substitute is '“why did I think we had an amazing time, given she ended up ghosting me?”

And now we get to see why he’s handed the answer to that straight to us.

Remember how we used symbolic cleansing to strip the Atlantic article down to what it actually knows, and get closer to the truth? Let’s try that here. I’m going to strip away any fluffy writing, filler phrases, or ideas he’s stolen from representations of romance that he’s seen elsewhere, and see what we have to work with.

Hi I’m a 28 (m) that went on two dates with a 28 (f).

We met on a dating app and started talking for about a week before we met up. So we met up for mini golf, went to the arcade, and had dinner for our first date. I did my best to make it a positive experience, was a gentleman, and paid for the date.We got to know each other and ended with a kiss.She texted me saying she got home saying she had a good time and even said I was a good kisser. I told her that I wanted to set up a second date in a few days because I was going on vacation soon. So we texted back and forth for a bit and set up a second date before I went on vacation.I had these funny dating flashcards setup as a way to break the ice too during our date. Even the bartender said that it was an amazing date idea that he wish he did with his wife. So we talked about a 3-4 hours before we went home.This time she payed for it but I offered that I was going to pay. But she said that I payed for everything the first date and that she wanted to be fair. So I didn’t fight it.2 days after our second date, I noticed she didn’t respond to my text as much and only like texted me toward the end of the night. “hey, (name) I hope you didn’t forget about me haha! I just wanted to make sure you’re doing okay”. As of today, I didn’t get a response for that message either. So I’m just confused to what happened? Was it my Instagram? I

don’t really post a lot nor do I have like crazy pictures. Mostly me just doing my hobbies like golfing, painting, cooking etc. and there’s not much to look at cause again I’m not a social media person.Was it the date? Did she lie? Was is it because she payed the second date?I asked my friends and they said that they don’t understand either and that the girl was not worth my time because it was messed up to do something like that. They were like she mislead you and you don’t want a girl like that.Any thoughts? What should I do?

Can you now see what’s weird about this recollection of events? This incredible girl, that he had an amazing time with, so good even the bartender noticed …. he hasn’t … told us … a single thing about her.

He told us more about some vacation he was going on.

Now you can say he doesn’t have to spill details about the girls he dates to strangers online, but how could he then also be asking us to explain her behaviour? How can he not see he’s left out all the details that might help us do that?

He’s left it all out, because he never took it in as it was happening. Look at how he went about it. He took her to the symbolic first date spot of the mini golf/arcade, brought the symbolically teen-movie cute date idea of the flashcards, and finished with the ultra-symbolically classic end of date kiss. How could he not think it was a perfect first date? It went exactly how he had planned it out. It’s exactly what he was told good first dates should look like. It was so well scripted he actually watched it from the audience’s (i.e. bartender’s) perspective.

The problem this creates is that the girl he was on the date with becomes irrelevant, she just has to play her part. She doesn’t even get any lines.

And that’s why her eventual behaviour seems so utterly incongruous. Look at the post title again: ‘Girl ghosted me out of no where. I thought we had an amazing time’. He’s genuinely wondering how those two things could be true at the same time.

It’s also worth noting that there’s a second angle to this that stopped him from perceiving the girl sat across from him, that some highlighting should make pretty obvious:

Hi I’m a 28 (m) that went on two dates with a 28 (f). We met on a dating app and started talking for about a week before we met up. So we met up for mini golf, went to the arcade, and had dinner for our first date. I did my best to make it a positive experience, was a gentleman, and paid for the date. We got to know each other and ended with a kiss. She texted me saying she got home saying she had a good time and even said I was a good kisser. I told her that I wanted to set up a second date in a few days because I was going on vacation soon. So we texted back and forth for a bit and set up a second date before I went on vacation. I had these funny dating flashcards setup as a way to break the ice too during our date. Even the bartender said that it was an amazing date idea that he wish he did with his wife. So we talked about a 3-4 hours before we went home. This time she payed for it but I offered that I was going to pay. But she said that I payed for everything the first date and that she wanted to be fair. So I didn’t fight it.

2 days after our second date, I noticed she didn’t respond to my text as much and only like texted me toward the end of the night. “hey, (name) I hope you didn’t forget about me haha! I just wanted to make sure you’re doing okay”. As of today, I didn’t get a response for that message either. So I’m just confused to what happened? Was it my Instagram? I don’t really post a lot nor do I have like crazy pictures. Mostly me just doing my hobbies like golfing, painting, cooking etc. and there’s not much to look at cause again I’m not a social media person. Was it the date? Did she lie? Was is it because she payed the second date? I asked my friends and they said that they don’t understand either and that the girl was not worth my time because it was messed up to do something like that. They were like she mislead you and you don’t want a girl like that. Any thoughts? What should I do?

Yes, his story about a girl he met, is actually a story about him. Even more interestingly, it’s a story about the person he thinks he is. He’s even trying to convince us of it too. I can’t bring myself to believe he brought up the golfing/painting/cooking because he thought it would answer his question. And therein lies a problem.

It’s like he’s tried to draw us a picture of her, but can’t open his eyes properly to see. And when you see how he’s recalling the tale, you can tell that when they were sat down for dinner on date #1, and he looked across the table, it wasn’t her that he saw. It was himself.

It was ‘I’m a guy that takes girls on romantic first dates’.

Even the bartender noticed.

I’ve made such an elongated point out of that post not because this represents some urgent crisis of modern dating or mental health. It might just take a few experiences like that for him to learn better and find someone to actually be present with.

I bring it up because I find it’s increasingly difficult to not have a little part of that guy living inside all of us. It’s sort of fundamental to development. Gaze with a capital G. I don’t really see how you opt out.

But the consequences are real, man.

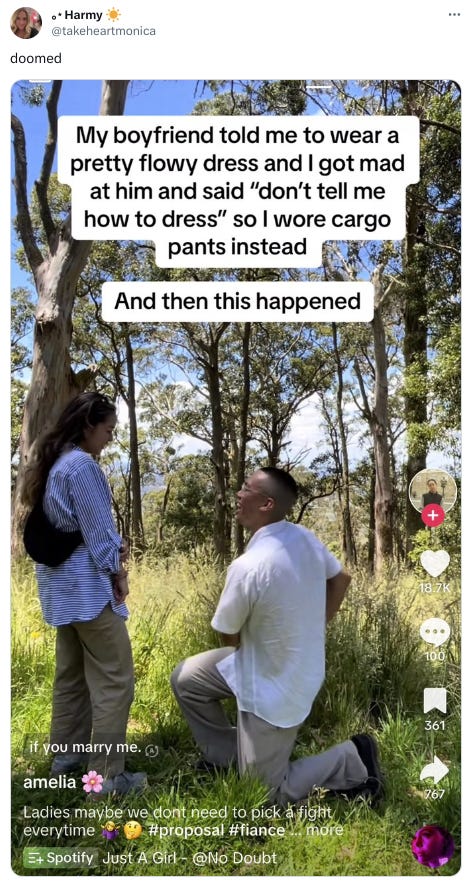

I bring up this example with caution, but remember this viral moment from last month?

And a much-upvoted response: “It's important to respect the people in your life and treat them as individuals rather than avatars of abstract concepts. It wasn't "patriarchy" that asked her to wear a dress, but she responded as if it was.”

Now, let’s not make that exact mistake and start taking this example very seriously. The fact they posted that means they found it funny and she said yes. But the insight on taking a person and turning them into a concept is useful.

It feels like a middle-class trend to work out what you symbolise in order to work out how to spend your time. What else do you think starter pack memes are about? The greater the influence of symbols on identity formation, the greater propensity to see anyone as a type. Just add the symbols together.

And the fact that romance is an easy lens to this stuff isn’t massively coincidental. Think about the difference between dating in 1994 and 2024.

In 2024, when you encounter a potential partner, you meet their representation first. Their Hinge profile is the drawing, and you’re the critic. You’re the Gaze. You have to make a best guess over whether this symbolic representation matches what you are after.

You get used to working out the type of person someone is from a small amount of information pretty quickly, don’t you? Like, we’re talking less than 5 seconds.

And the invariable consequence, because there’s no better strategy, is to have some types you’re looking for. That’s the efficient way to sift through the masses. And when you make your own profile, you have to play the same game, and make it clear what type you are too, so the right people can spot you.

If you swipe right on someone, it means they are above the threshold of symbols you wanted to see, going off some sub-conscious checklist. If it’s a match, then you both feel that way. (+ obvious mutual physical attraction above required threshold)

That is all so obvious to everyone. But here’s a weird thing people talk less about: it creates a really psychologically bizarre first date situation. I wasn’t around at the time, but it feels like pre-app first dates is when you learned about the person, and you feel out compatibility.

But now … that’s kind of done in advance. Once you’ve, swiped, matched, chatted, switched to whatsapp, and agreed to meet .. your image of that person is actually quite strongly built. The vetting process has happened, for both parties.

And crucially, the representation is what you’ve decided you’ve liked. Going through with the first date is almost a formality. Because, at some level, you’ve already decided there’s more to come. You know how the first date’s going to go.

(aside: I find it hard to tell if that is going to sound absolutely insane to people who haven’t used dating apps in big cities. I do however know my audience so probably not worth wondering about those people too much.)

The issue is that this is at the beginning of the same spectrum our Reddit Romeo was on. He wrote out the date he wanted in advance, with the type of girl he always wanted to meet. And he actually *experienced* the date as going that way. That’s the amazing part. And it makes me wonder how many people have fallen for someone’s profile, been excited by them for about 3 weeks, and then been shocked when they start acting out of character.

“She’s not the girl I thought she was”.

Yeah, exactly.

So, what does this have to do with hanging out with friends, and yearning?

The first thing to say, non-judgementally, is that the psychological manifestation of over-reliance on symbols, and pressure to display the right ones, is a type of narcissism. Not in the Great Gatsby way. In the Christopher Lasch way. Like the reddit date guy. A pre-occupation with having everyone and everything around you validate the story of who you are. Because you’ve been taught that that’s really important.

And one of the symptoms of this, which is the reason I brought up that whole dreary story, is alienation. Both alienation from self, his only self-conception exists through symbols and external validation (i.e. ‘I’m the type of guy that..’), and alienation from others (i.e. the ability to go on two dates with a girl and still know nothing about her).

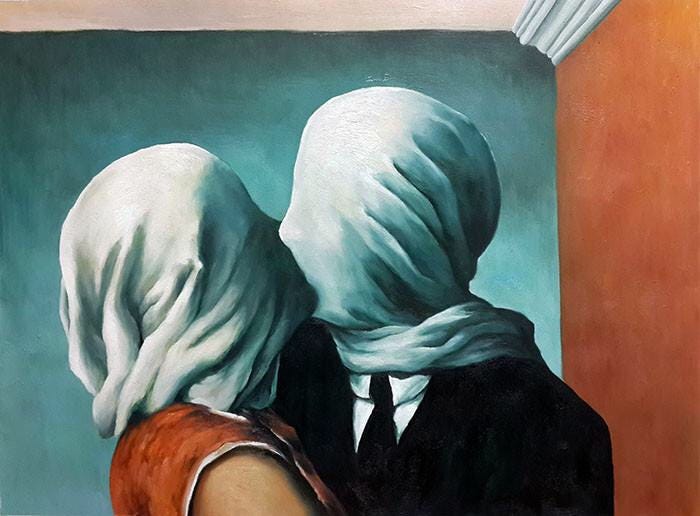

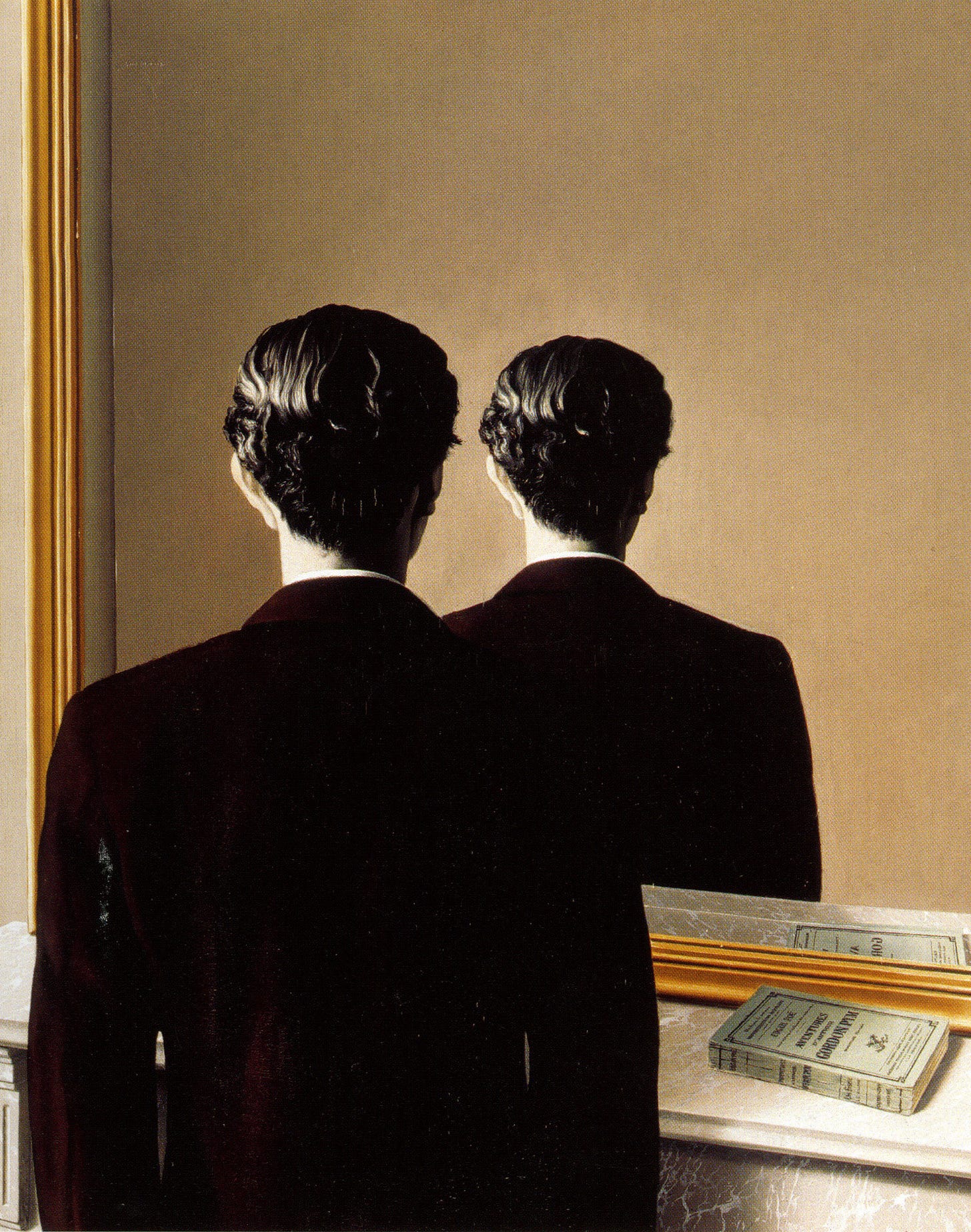

Put it this way: connecting with others is harder the greater the symbolic load you are placing on that relationship, because it stops you from seeing what’s in front of you. Same thing goes for your relationship with yourself. That’s why you have a complicated relationship with mirrors. That’s why you’re bad at drawing.

But there’s another consequence of these types of alienation. When you’ve lost your ability to perceive what’s in front of you, or indeed, you’ve chosen to prefer the version of reality inside your head than what’s really happening: your real life moves closer to simulation.

Like, it’s easy to look at the Vision Pro and say ‘Wow, simulated experience so detailed it may as well be real. Baudrillard was right, hyperreality is here!’ Cue 100 meh think pieces.

But what all those think pieces will leave out is that this is just a manifestation of hyperreality, where the digital and the physical are literally blended in front of your eyes, and that the real cause isn’t just better technology.

Because what actually enables hypperreality to become the default way of being is real life experiences so loaded with symbols that they may as well be simulated. That’s Apple’s actual market opportunity, and we created it years in advance. Buy, buy, buy.

So, to catch us all up. Here’s the situation:

The Atlantic asks why people have stopped hanging out

And their answer is loaded with enough symbolism, that by the end of the article, you forget what it was even about

Dazed ask what it is that people are yearning for

And their answer is we need to find a good balance between the digital and physical world. A sentence so symbolically correct they don’t notice it literally doesn’t make sense in response to the original question

What both writers did by accident was that they let the symbols in too quickly.

In the Atlantic: “The first explanation is so obvious that it scarcely needs mentioning. Americans are spending less time with other people because they’re spending more time with their screens—televisions and phones.”

The problem is that this is true, but you can still get deceived by it. Where this goes wrong is you read the word ‘screens’ you think of every single other similar column you’ve ever read, and you add them as footnotes to this sentence. Screen time, dopamine hits, the algorithm, digital selves, Mark Zuckerberg, China are stealing our data via TikTok, Instagram makes teen girl depressed. This is decided as having done the damage before the question even needs to be asked.

You see someone staring at their phone screen, and choose to focus on the screen, because that’s what is collectively agreed is important. You forgot there was a fully formed human being there. The Atlantic forgot too.

Your brain does this so confidently that it’s no surprise that this conclusion turns up a few sentences later: “Face-to-face rituals and customs are pulling on our time less, and face-to-screen technologies are pulling on our attention more. The inevitable result is a hang-out depression.”

What’s happened is both reader and writer have constructed a narrative so symbolically sound so quickly, that the word ‘inevitable’ can get used and no one bats an eyelid.

The real clue is contained just one sentence before, where the author mentions the decline in local communities: “America is suffering a kind of ritual recession, with fewer community-based routines and more entertainment for, and empowerment of, individuals and the aloneness that they choose.”

Can you see the key word? Hint: it’s the last one. There’s our real question.

Take the original idea: Why have people stopped hanging out and started looking at screens?

and give it the simplest twist:

Why have people chosen to stop hanging out and start looking at screens?

Similarly, the question Dazed should be asking isn’t ‘Why are people going on less dates having less sex?’, it’s ‘Why don’t people want to go on dates and have sex?’

Don’t stop there, The Atlantic gave us one more reason we don’t get to see our friends anymore: there is no time to.

The second explanation is that people are hanging out less because we’re all so damn busy. As The New York Times’ Jessica Gross notes, people in their 30s and 40s have less leisure time than they did two decades ago.

The problem is that this doesn’t just happen. Leisure time is an abstract concept, it’s not like the weather. It doesn’t just come and go. We choose what fills the time. If you think it’s some greater force choosing it, then see last post. In fact, probably the hardest psychological/economic/sociological questions we face is why we are now so affluent and technologically advanced, but somehow work … more?

Why have we allowed that to happen, rather than fight for the alternative?

And so, I’ll tell you what I think a more useful Atlantic article would have been. Scratch out ‘why people aren’t hanging out’.

Write down the more uncomfortable question:

‘Why don’t people want to hang out?’

And I’m gonna try answer it.

To make sense of the things people want to spend their time on in 2024, I’m going to have be annoying and explain where wanting comes from, and what it looks like. I do at least promise that if you take away one useful thing from this essay, it’s going to be this bit.

(Also, I did warn you about this being a Lacan essay. So here we go.)

Approximately two important things happened to you before you turned two years old. The first is you learned how to speak. The second is you learned about you. As in, one day, your mother picked you up, held you up to the bathroom mirror, and said something like ‘hey look its you! wave!!’

And that’s pretty much when things changed forever.

Maybe your eyes widened. Maybe you laughed. Maybe you actually waved. Your mother got excited either way. But internally, for the first time, you got it.

That combination of head, torso, arms and legs. That was really you. That’s what other people saw. You were cohesive. You had an identity. A story.

At the same time, you’re grasping what words mean. You start to use the word ‘I’. You learn words for all kinds of things. And when you look in the mirror you see them around you, and you see how you fit in with those things.

Words meant you could see 10 completely different dogs in your colouring book, but still have a word that turned them into a unified concept. Your brain starts to see them as the same thing.

On each day of one week, you could act as if you had a completely different personality, with different obsessions and behaviours. And on Sunday, you look in the mirror again, and you still see yourself as one unified concept. That’s who ‘I’ am.

But that concept is a reflection, both literally and figuratively. Which means there’s a distance, no matter how close you press your nose to the glass. There’s an abstraction.

You exist, but you’ve been outsourced. The version of you that now counts to your self-conception is the one staring back at you, not the one that takes it in. The one in the mirror is the one with an identity. With a story. And that story only make sense when you see yourself fitting in with all the other things. With all the other words. With all the other symbols.

From that moment on, you’ve been more than a being that behaves on pure instinct and sensory input. That behaviour got added up into something more. Your vision became mediated.

You entered the world of symbols, and you would never leave again.

As you grew up, you learned the world was much bigger than just your house. You learned the world has rules, and society has structure. When you looked in the mirror you saw someone existing within that structure. Your brain actually saw it. Which makes you only interpretable through this bigger picture. You don’t make sense, as a concept, otherwise.

You learned your place.

But the fact you are reading this suggests this wasn’t so simple.

For the first time, you didn’t want just food and sleep. You saw the whole game, and realised they were tools to help you play it. For the first time, you wanted to be something.

But that thing you wanted to be was unified. It was cohesive. And you really aren’t those things. You think, speak, behave, move, even look slightly differently every day of your life. There’s nothing unified about it.

Your reflection, however, doesn’t have this problem. The fragments are papered over. You appear whole. Your story appears to make sense.

The world of symbols told you what to want, but you got handicapped by reality. You saw something you were not, and could never be. You felt a void, and you became compelled to fill it, even though it would never be possible.

For the very first time, you desired.

So, there is a grand irony to the Dazed article’s conclusions on the tragedy of yearning for something you can’t grasp. This article is likely wrong is various ways, but implying this is a bad thing is definitely wrong. Because this is the only type of desire that is worthwhile. This is the cognitively healthy way to be. Frame it as a void if you want, but fucking hell, be glad that it at least gives you something to do. Be glad that your story didn’t finish when you recognised yourself in a mirror for the first time. Be glad you have something to want.

When a pianist first sat down at a piano when they were 3, they were handed an impossible task. They can play every waking hour for decades, and there could still be someone a whole class above them. And even that person has the same impossible task, because you can’t complete playing the piano. You can never perfect it.

But you can try. You can see just how close you can get. So every day, they sit down and try to get closer to perfection. It’ll take them to amazing places, both internally and externally. But it won’t ever be enough, so they have to keep returning to try and do more. Then one day, they sit on the piano bench for the last time. They die that night in their sleep, having run out of time to compose the masterpiece they dreamed of since they were a kid. They yearned for something they would never be able to grasp. And it was a life well spent. They had something to want.

The corrupted human spirit is not one that sets unrealistic ambitions, it’s one that doesn’t know how to set unrealistic ambitions, realise those ambitions are unreachable, and get to work anyway. That’s the person that’s never learned how to desire something.

The issue with the people described by Dazed isn’t that they are spending their life yearning. It’s that they’ve found a situation where they are yearning for nothing in particular, with no clear path of action. Hence, google searches for ‘yearning’ and ‘longing’, rather than ‘how to get rich’, ‘cool places to travel’, or ‘fun things to do with your friends’.

This is desiring desire itself. This is wanting something to want. That’s why I titled this thing after that TikTok meme. And this feels like a problem, because it suggests a disconnection from self.

Makes me think of something from Sam Kriss earlier this year, on incels:

They would like to feel the sense of dumb animal contentment you get when another warm and living human being touches your skin, but they can’t, and so they kill. This makes sense. What doesn’t make sense is the fact that overwhelmingly, these people make no effort whatsoever to meet other people. They say they want love and touch, badly enough to go on shooting sprees about it—but not badly enough to try. Much weirder territory here. Something’s gone wrong, but what? It makes sense to think of social problems in terms of people not getting what they want. This is the little engine that’s powered all of human history, from the dawn of agriculture until the day before yesterday: the uneven distribution of the surplus. But now, we’ve broken out of history and into something else, and the true nature of our problem is something much slipperier: not the repression of desire, but its disappearance."

Isn’t it so annoying when someone is that much of a better writer than you are?

Anyway, back to the pianist. What if he was never taught to set a goal like that? What if he no longer saw a need to try get better every day? If that wasn’t a part of his life, and he no longer had anything to want, what would he spend the time on? How would he know how to spend it?

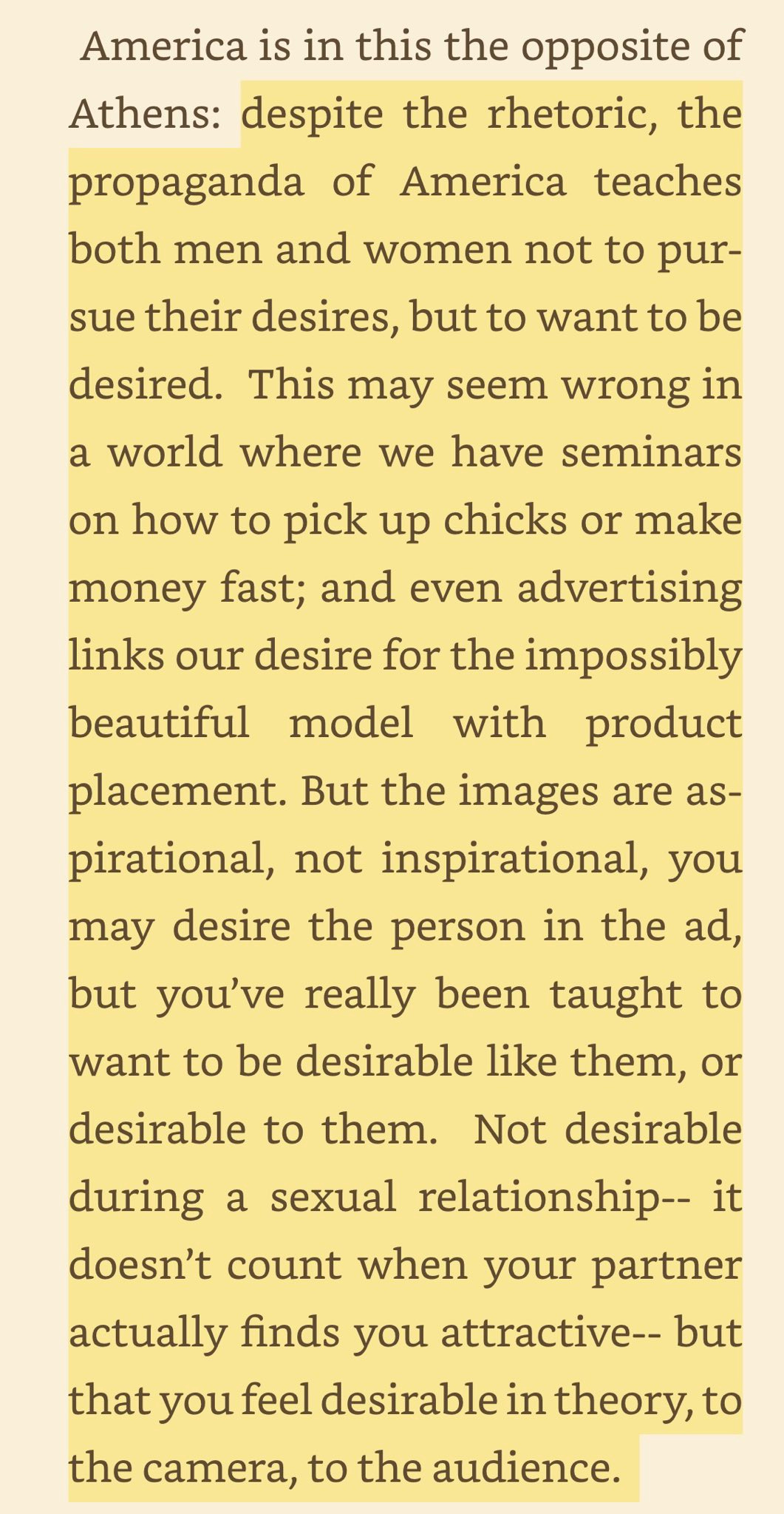

That’s the person that needs someone else to tell them what to want, and so relies on the symbols of status and success they see around them everyday. In media, in advertising, in conversation, you encounter the symbols of a life well lived. And so you move toward them, but what you get blinded from is who sets the target.

There’s two layers of cons to any good marketing strategy. The short con is telling you that spending time/money on their product gets you closer to the life you desire. The long con is convincing you that you came up with the idea of desiring that life in the first place.

Stretch this out to the whole symbol ecosystem and you see the genius. Because it matches the criteria for desire, it traps you in a situation where you are chasing something you’ll never reach, which means you’ll keep doing it until you die. And you’ll think you’re doing the right thing. The difference is, there’s no clear picture of what you’re chasing. There’s just a sketch. There’s just an idea.

But your brain treats these symbols and ideas as real life. So you can’t see your own problem. You end up walking around the real world, but perceiving a symbolic one. Everything only makes sense as part of a story. When you’re asked to recount a day in your life, you can’t help but tell it through markers of identity, that explain what type of person you are. When you’re asked to draw a picture of yourself, it comes out like a kid made it.

Which means you’re living through things by being there physically, but caring more about the version in your head. That’s the one that counts. It either means you’re simulating the part in your head, or the part in the physical world. And when you’re actually not sure which one of those it is anymore, we have arrived at alienation.

And this is when you forget how to desire things.

If the only version of yourself that counts anymore is the one sketched out on the paper, with your various symbols of success assembled around your stickfigure body, then you’re no different from the Reddit date guy. You’ll accidentally spend your life making sure other people can see what you want them to see. You’ll care about that so much, that you won’t be able to learn anything about a girl that’s given you her whole evening. Twice.

Suddenly you have a new void. Something you can spend forever trying to close. The gap between how people see you and how you want them to see you. You might not like it, but this is modernity. The Last Psychiatrist:

Now say there isn’t an audience. That your time has been freed up to do whatever you want without the gaze of others. You can thank the graces of macroeconomics and technological progress, and soon enough AGI, for that one.

Liberation. How to use it?

The problem is that someone lost in symbols has no idea. They don’t want stuff. They’ve forgotten how.

The great promise of advanced AI is that it gives everyone the time to spend their days pursuing their passions. But … like … what passions? We can’t even get these teens to want to have sex with each other. Now they’re going to be artists just for the actualisation returns?

Theorists look at people and wonder how can we give them more time, so they can hang out with their friends or other rewarding things with their lives. So they can finally reach all of the things they’ve been apparently yearning for. This misses the point.

Because they already had the chance. They could have been hanging out with people. They had the time. And they filled it with scrolling and emails.

The irony the Atlantic and Dazed failed to pick up on is that they are a facet of this exact process. They supply what the market demands. They answer their own question.

Ask yourself why they exist. Genuinely. What are they for?

They’re not where you go to find the latest in pop culture and current affairs. That’s what Twitter and Instagram are for. So what’s the service?

Think about it this way: They’re funded by traffic, and I am by admission a sample of that traffic. So change the question to this: Why did *these articles* appear in *my feed* and why did *I* click on them?

When I spent 20 minutes reading them, what was the opportunity cost? Go back the drawing book from the start of this, and draw the negative space. Colour in everything else, so you can more clearly see what’s in front of you. What does this mean I’m not spending time on?

Pay less attention to what information the articles are telling me, and focus on how they are telling it to me. It’s McLuhan’s The Medium is the Message in plain sight. Where the medium is publications like The Atlantic, and the message is ‘use us to fill your spare time so you don’t have to face the void that exists outside’.

You know how I know this is the case? Because one evening last week I found myself reading that article about American time use, when I could have been hanging out with my friends. And that’s the message: time filling. There’s a reason the New York Times worked out their best shot at survival was becoming a games website. Let’s see what an 80-year long Wordle streak looks like.

And so this is how society arrives at hyperreality. Everyone refrains from real life experiences and passionate pursuits, because (1) we find it harder to connect with others and (2) we find it harder to connect with ourselves. So we move closer to simulation regardless of how good the technology is.

We end up with symbols that started off representing something, but now we’ve thrown away the evidence, and just the symbols remain. No one’s sure if that makes them any different from something you can hold in your hand. Which means looking like the thing is as important as being the thing, and it’s a hell of a lot easier to achieve. This is how culture and discourse about culture become the same thing. This is how people become media. Say goodbye to years of solo craftsmanship in the pursuit of something great and say hello to dopamine hits.

But there is a good twist to this.

It’s a twist that arrives the moment you realise this isn’t society’s problem. It’s yours.

And the solution outlined above won’t work. Something won’t feel right. It wouldn’t even work on an infant. Remember when you saw yourself in a mirror for the first time? The wholeness of your reflection was desirable, but you knew you were more fragmented than that. That was a gap that could never be filled.

You tried filling it anyway, and that was the right thing to do. But the issue with hyperreality is that it gives you ways to not see yourself that way. It tries to paper over the cracks. Your identity is created. And the desiring stops.

That is, until you learn how to turn it back on again.

Because understanding the rules your brain was playing by works surprisingly well. You can force it to stop taking other people and replacing them with a sketch. You can find a way to see what you’re missing.

You can always relearn how to draw.

I think there is also a common loop where you recognize yourself slipping into a type and recognize it could be (must be!) the result of a bunch of empty posing, irony, marketing, etc, all the things you mentioned - so you think "ugh, this must not be really my true self", and reject that desire and look for something else, so you can make sure to not become "that guy", and then you keep doing that until you're spending your time on Saturday morning reading a long substack article about the end of desire and then commenting about it instead of doing literally anything else.

Plenty of insights. But reality without symbols to filter it is lovecraftian, nightmare inducing: that's what the existentialists tried to tell you. The cinematographic identity is the how we evolved not to become mad at the unadulterated realness of things, and beyond the repulsiveness of what we see without symbols (the meat of the flesh, the disgusting processes). Because in the end, if we remove all symbols we would only see death, impending. And the Thing that looks unflinching at death and does not go mad is not a human anymore, and has no desires.

In french, all the things we choose to spend time on for fun are called distractions.