Why Making Up for Lost Time is Hard

Let’s pretend that six months ago your best friend had a break up.

A pretty bad one. Understandably, they decide to take a few months for themselves.

Over that time, they either truthfully or artificially arrive at the conclusion that their ex wasn’t really for them. They’re over it. So it’s time to reenter the dating world. Hinge profile built, likes coming in.

The options are numerous, but your friend is still a bit hesitant, so they message you for advice. It’s been a while, and these people could be murderers.

You have a plan to help them get back in the swing of things (not a euphemism). It basically comes down to ‘Ease yourself in!’ You tell them to just go on one date this month. Next month is May and hey summer evenings are getting longer, go on two. In June, double again to four. And just keep going with that pattern until you find love again.

They thank you for your advice and switch from WhatsApp back to Hinge before you notice an issue. You switch to your calculator app.

So in March they’re not dating at all. And then they do indeed start easing themselves in. But things seem to get out of control fast. In June they’ll do one a week, but in September it’s one a day. If they work and sleep like a normal person, then in December they’ll be spending all of the rest of their time dating, rotating partners every hour. By the time we’re back around to April, they have sacrificed both work and sleep in the pursuit of love, and their life is a 24/7 dating bonanza where they meet someone new every 10 minutes.

If they are still single by then, they are probably the problem. But if you reckon your friend won’t realise that, or you just don’t want them to ruin their bank account by the end of summer, then you need to tell them now.

The momentum has started and date #1 is happening. They’re having a coffee at one of the window tables in a cafe. The non-murderous prospect isn’t great with eye contact, and is finding comfort staring out the window. Well, it was comforting until they spot you. Sprinting at the window full tilt. You’ve got a piece of paper in hand.

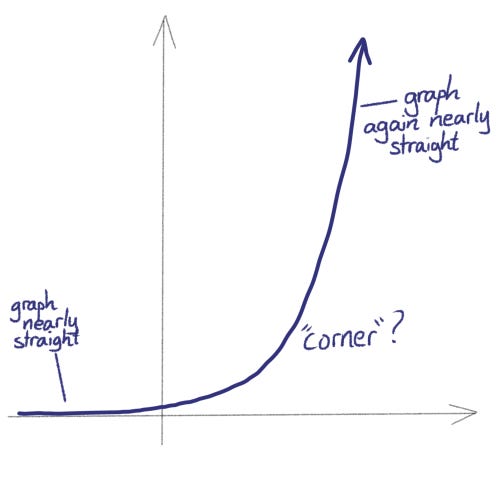

The whole coffee-shop turns at the noise, as just between the heads of the potential lovers, you’ve slammed this drawing against the glass:

One of the greatest threats to humanity is the failure to grasp exponential growth. At least, that’s what people are saying. An even simpler way to put it is that we struggle with things that double.

That was my far fetched illustration of it, but there’s some you’ve probably heard before.

You may have seen this TikTok:

You may have also come across the lily pad problem:

Imagine a large pond that is completely empty except for 1 lily pad. The lily pad will grow exponentially and cover the entire pond in 3 years. In other words, after 1 month there will be 2 lily pads, after 2 months there will be 4, etc. The pond is covered in 36 months.

I will remove any mystery and tell you this next bit is the bit that is important:

If I asked you when the pond would be half filled with lily pads, the temptation would be to say 18 months – half of the 36 months. But the right answer is 35 months. Right before the pond is filled, it’s half filled.

By the time you can see you’re close, it is already over.

Behavioural science gives this limitation a name: Exponential growth bias. The tendency to perceive things as growing linearly even when they don’t. I’ve even seen researchers call it EGB (I will not be joining them).

Things that grow exponentially tend to start harmless, creep around at that level for quite a while, and then explode. We more easily understand things that grow a bit, then keep growing a bit, and in fact keep growing at that same pace forever, bit by bit.

I can see why there wasn’t much need to think exponentially when the brain evolved. Walk for 1 day, you'll travel 10 miles. Walk for 5 days, you’ll travel 50. Collect berries for half a day, feed the family for a week. Go full day berrying, that's two weeks of food (was not there, cannot confirm if accurate numbers).

Most cognitive shortcuts serve us well most of the time. And, to be fair, most things in life increase and decrease fairly linearly. And my mate’s not had a breakup. And I don’t even have a garden, nevermind a pond. So why stress?

‘Man stares at what the explosion of the atom bomb could bring with it. He does not see that the atom bomb and its explosion are the mere final emission of what has long since taken place, has already happened. Not to mention the single hydrogen bomb, whose triggering, thought through to its utmost potential, might be enough to snuff out all life on Earth. What is this helpless anxiety still waiting for, if the dreadful has already happened?’

Here’s a list of things that grow exponentially:

Compound interest on savings and investments

Compound interest on debt

Here’s a list of things that people don’t think about until most of the damage is well underway:

Whether a new virus requires special government measures (I don’t need a source for this)

Whether we should try new energy sources (or this)

You’ve heard the phrase ‘making up for lost time is hard’ right? Well, sometimes it’s harder than others. It just depends on what the growth curve looks like.

That quote about the atom bomb is from Martin Heidegger. But I first read it in RD Laing’s The Politics of Experience. The point of it is that well timed action will often feel too early. And by the time it feels right, when the dangers are finally within your eyesight, the show has already begun. You may as well sit back, because after all, what is your helpless anxiety still waiting for?

The second psychological issue here is that preventing future issues requires action now, and now feels.. different.

To anyone who ever took Behavioural Econ 101, this is going to be a tired example, but it’s useful.

Here’s two choices:

Choice one: I give you (a) £10 now or (b) £15 in a month.

Choice two: I give you (a) £10 in 9 months (b) £15 in 10 months.

I will skip the airport pop sci spiel. In these scenarios, people tend to pick (a) in choice one then (b) in choice two.

This is called present bias. We like immediate rewards over long term benefits.

It’s part of how procrastinating an essay happens. It’s part of how the diet starts tomorrow. It’s part of putting off going mole mapping. It’s part of waiting until your next paycheck to start putting money away. It’s part of one last credit card payment.

In fewer words, there will be a right time to do the thing, and that time, well it definitely isn’t right now.

I’m a believer in actions having reactions. So what’s the flipside of the present getting special treatment? The future gets mashed together. A vague other place, where a different version of you exists. The one that can’t succumb to temptations, the one that goes about their goals with ruthless efficiency. This guy explains it pretty well.

Why would you take £15 in 10 months over £10 in 9 months? Because to present you, they are exactly the same distance away. They’re both ‘over there’.

In any case, prioritising comfort doesn’t seem like that big of a deal. I procrastinated every college essay I ever wrote, and paid the consequence of the odd late night, but I still graduated college. I’ve probably had more fast food than I’d like to think, but I still joined a gym eventually.

So sometimes I put off something that’s going to be more annoying the longer I leave it, but how much more annoying could it get? Ah, just one more day of self-care, and my problems will just get a little bit more stressful. I’ll still sort them eventually. Right? Hmm. Why has my credit card just bounced? What’s this on the news about a lockdown? And where did all these lilypads come from?

I’m hoping you see what question we’re circling around here. We’ve seen what exponential (or just super-linear) growth looks like. We’ve discussed what the present and future feel like. Where are we going with this? Well, if you thought the first scenario about your friend’s dating life was far fetched and contrived, I’m sorry for what’s about to happen.

When you slammed the growth graph on the cafe window, your friend pretended to not know you. I think that’s probably fair enough. To cheer yourself up on the way home, you veer into the carnival that’s just started running for the summer.

So let’s pretend that this new carnival in town has a fresh, incredibly contrived version of pin the tail on the donkey. Except you’re the tail getting placed, and the donkey is a flat 50m bar that curves directly upward at the end. As you’re getting blindfolded, the carny offers you a prize of £20 if you can correctly guess where he’s placed you on the curve.

You say you could.

He asks “are you willing to bet on it?”

If it’s the vertical bit, easy money right? You’ll fall right down, you don’t need sight to see how extreme a part of the curve you’re in. £20 and a concussion up.

But let’s say he lets you go and you can stand up straight. Now the task is harder. Are you at the very start of the curve, where the forces of doubling are only starting to grumble. Or are you at the very end of the peaceful period, and in fact there’s a sheer incline approximately two metres in front of you.

Do you see the problem? To you, those two states would feel exactly the same. But they are drastically different, they could be 49m apart.

Tim Urban even explained this in a much easier way 8 years ago:

Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick sums up the cultural moment as us, having fucked around, now finding out. Things got out of our control, and now we’re left staring, waiting to see what the consequences are. It reminds me of something from earlier.

‘Man stares at what the explosion of the atom bomb could bring with it. He does not see that the atom bomb and its explosion are the mere final emission of what has long since taken place, has already happened. Not to mention the single hydrogen bomb, whose triggering, thought through to its utmost potential, might be enough to snuff out all life on Earth. What is this helpless anxiety still waiting for, if the dreadful has already happened?’

I’m not going to ask you if the dreadful has already happened.

That’d be a hard question.

Slightly easier questions though.

Where actually are we on this graph? And are you willing to bet on that?

"A little sleep, a little slumber,

a little folding of the hands to rest,

and poverty will come upon you like a robber,

and want like an armed man."

This is a well explained version of a pet-peeve-idea I got from two videos published 30 years apart:

- 1994 Danny Hillis' TED Talk: Back to the future (of 1994): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gdg4mU-wuhI

- 2023 Tom Scott's video: My worries about the trajectory of A.I. [relevant part 00:25 - 02:38] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jPhJbKBuNnA

Both show a sigmoid curve with a exponential-ish first half to represent progress. My take is that, not only we don't know where on the curve we are, we've been lost for (at least) the last 30 years and we've made no progress with our estimations.

We're living interesting times.