There's a reasonable chance that you're seriously running out of time

who knows the real price of individualism?

I.

Health is much more difficult to deal with than disease.

Donald Winnicott said that, according to Adam Phillips. I’ve never been able to validate the quote myself.

If real, he is of course very right. This is the essence of all psychology. Or at least all the parts that matter.

Flip the frame. Managing a disease is much easier than managing good health. Your next action is always much clearer. Less questions. Narrower goal. Every move is meaningful.

Such an asymmetry is also part of the basis for Prospect Theory. Kahneman and Tversky observed participants feeling losses more strongly than equivalent gains - we want to avoid losing more than we want to win, at least in financial bets. Just as disease (a loss) commands our attention and action more clearly than health (a baseline state), losses motivate us more powerfully than gains. This is loss aversion.

In his explanation of why humans might be like this, Kahneman’s best guess is a survival mechanism of times gone by. In our ancestral environment, losses (like losing food, shelter, or social status) could be life-threatening, while equivalent gains were merely beneficial. This asymmetry made it adaptive to be more sensitive to potential losses.

Awesome, how come it’s not true?

Loss aversion varies intensely by culture, and is empirically much higher in Western, rich countries compared to third world African countries. As a logical extension, loss aversion based nudges tend to have no effect at all in countries like Tanzania and Uganda. It would seem to me that the question isn’t why humans are naturally loss averse, it’s how has the development of the West potentially caused this kink in human rationality?

(note: there are also studies that cite the opposite finding i.e. that loss aversion peaks in the third world, and is lowest in a country like the USA. my personal view is that the proxy dependent variable they are using across every nation is essentially useless, so these results don’t really mean anything. i think this might also be why it’s so hard to find the actual details of it in their papers. some in the same series also only manage to compare North America and Europe. ah yes, the two most widely differing cultures on the globe.)

One thing Wang and team spotted in their data was the connection between loss and aversion and a country’s economic status gets severely weakened once you also consider the role of individualism. Individualist countries are more loss averse on average, and the authors make this note on collectivist countries:

according to the “cushion hypothesis,” social support from the in-group network provides a “cushion” for potential financial losses, inducing lower perceived risk and consequently less risk-averse behavior

Whereas in individualist cultures, we don’t cover for each other like that. You’re kind of on your own. Hence, being more scared of losing what you have weighs heavier than the excitement of getting more.

(I’ve covered the rise of individualism before: here, here, here and here. TLDR: technology means you don’t need other people as much, increasing % share of GDP coming from discretionary income, much more life spent on the project of ‘you’. Pretty straightforward.)

But what I think the papers above fail to cover is that the real effect of individualism is not to completely remove the ‘cushion’ the authors speak of, but more to move it to a different seat. We still have some trust that we’ll be caught when we fall, the trust is just at a different level. We have much more belief that the system is looking after us. So you don’t need your family/neighbours to.

Rules and norms are made clear, one follows them, one leads a safe and happy existence. If I don’t change anything, I get to stay safe. And we end up with loss aversion again.

But this is where you realise that loss aversion is nothing compared to the bigger bias you end up with.

I once heard this thing about zebras and human behaviour, that annoyingly stuck with me as quite true for something so contrived. Here we go. Why do zebras have stripes? They’re a form of camouflage, right?

Well then how come it makes them stand out more than any other animal I’ve ever seen? I could spot a zebra a mile away, that’s hardly effective. Turns out they’re not camouflaging against nature, they’re camouflaging against each other.

This matters, because when the lions turn up and the zebras run, the zebras all blur into one another. The lions have to power to target and kill any single zebra, but the blur makes it harder for them to communicate to each other which one to go after.

As long as you look like all the other zebras, you’ll probably be fine.

Which is mostly a good idea in life, right? You know nothing about education, send your kids to a regular school. You know nothing about economics, have the same portfolio as everyone else. You know nothing about what you’re actually supposed to be doing with yourself, pick a well-trodden path. The normative way must be the normative way for a reason.

Put it this way:

Collectivist cultures: we have to look out for each other, because no one else is going to. I trust you’ll have my back because I have to have yours too.

Individualist cultures: we don’t have to look out for each other, because in the aggregate, the system is going to. You don’t have to have my back because we will never be truly allowed to get in danger.

When you fall in a collectivist society, you land on people. When you fall in an individualist one, you hope you land on policy. Staying in line is safe, because the system is built to keep you safe.

Consequently, nothing could ever be worth panicking about. There’s just no way the world would do that to me. That, friends, is the social contract.

II.

I’m becoming less and less convinced that the invisible hands are going to catch you when you fall next time. Because the system’s going to get caught off-guard too. At least in the short to medium term.

I’ve been reading a lot of well-thought out work recently.

Scott Alexander and Dan Kokotajlo (& team): - AI 2027 (a median forecast):

December 2027: From human decision-makers’ perspective, their AIs are the best employees they’ve ever had access to—better than any human at explaining complicated issues to them, better than they are at finding strategies to achieve their goals.

…

Late 2029: Humans realize that they are obsolete. A few niche industries still trade with the robot economy, supplying goods where the humans can still add value. Everyone else either performs a charade of doing their job—leaders still leading, managers still managing—or relaxes and collects an incredibly luxurious universal basic income. Everyone knows that if the AIs turned on humans, they would be completely overpowered… There are cures for most diseases, an end to poverty, unprecedented global stability, and the Dow Jones just passed one million. Some people are still scared or unhappy, but their options are limited. They can either enjoy the inconceivably exciting novel hyper-entertainment on offer, or post angry screeds into the void. Most choose the hyper-entertainment.

Dean Ball, the new White House senior AI policy advisor - Where we are headed:

Corporations that adopt agents will have far greater capacity for intellectual labor. Teams of thousands of sales agents or coders will accomplish (some of) the firm’s work in far less time than was ever conceivable before; they will be able to do much more work as well. They will be able to be scaled up and down dynamically depending on the firm’s needs. Information will flow rapidly and in high fidelity between different teams of agents to employees, managers, and company leadership.

Once the pace and direction of automation becomes clear to firm managers, they are likely to employ junior-level humans only in areas where:

They legally have to. For example, the widespread state-level algorithmic bias bills also usually have provisions requiring businesses to offer “human alternatives” to “automated processes” like customer service. In this case, I suspect US states that adopt these policies are mostly creating a jobs program for call center workers in developing countries, rather than Americans, but I digress.

There is a component to the role that requires labor in the physical world (this does not just mean blue-collar work; for several years of my early career in policy, an important part of my job involved overseeing in-person events).

The candidate is extraordinary, of a level of obvious quality that firm managers wish to cultivate that person to assume higher ranks in the organization. For those taking this path, it will almost feel as if average is over.

I can imagine plausible scenarios where this does not become a problem, but the blasé attitude of many libertarians strikes me as wide of the mark. Millions of young people who planned to enter high-paying knowledge work sectors could very well be starved of the opportunities for which they trained in school. Elite overproduction is often a bellwether of political instability, and America probably already overproduces elites. Given the other political, social, and economic turmoil America is likely to face over the coming decade (AI-related and otherwise), this is a substantial risk.

I am aware of very few good policy proposals that have been put forth to deal with labor market turmoil.

Helen Toner, former OpenAI board member who left after the Altman fired/rehired situation - "Long" timelines to advanced AI have gotten crazy short:

What counts as “short” timelines are now blazingly fast—somewhere between one and five years until human-level systems. For those in the “short timelines” camp, “AGI by 2027” had already become a popular talking point before one particular online manifesto made a splash with that forecast last year. Now, the heads of the three leading AI companies are on the record with similar views: that 2026-2027 is when we’re “most likely” to build “AI that is smarter than almost all humans at almost all things” (Anthropic’s CEO); that AGI will probably be built by January 2029 (OpenAI’s CEO), and that we’re “probably three to five years away” from AGI (Google DeepMind’s CEO). The vibes in much of the AI safety community are correspondingly hectic, with people frantically trying to figure out what kinds of technical or policy mitigations could possibly help on that timescale.

It’s obvious that we as a society are not ready to handle human-level AI and all its implications that soon. Fortunately, most people think we have more time.

…

But recent advances in AI have pulled the meanings of “soon” and “more time” much closer to the present—so close to the present that even the skeptical view implies we’re in for a wild decade or two.

[This means that] dismissing discussion of AGI, human-level AI, transformative AI, superintelligence, etc. as “science fiction” should be seen as a sign of total unseriousness. Time travel is science fiction. Martians are science fiction. “Even many skeptical experts think we may well build it in the next decade or two” is not science fiction.

Bear in mind the first quote is from the median prediction from the most heavily research forecasting project I’ve come across. Bear in mind the second quote “I am aware of very few good policy proposals that have been put forth to deal with labor market turmoil” is coming from someone who is now leading AI policy in the White House. This is not a thought exercise.

Which means I am now on board with the last quote’s accusations of unseriousness levelled at the ‘AI is hype’ crowd. You are blindly believing in the safety of status quo.

I always thought this blog would be most useful to young people. It’s hard to change yourself or your life when your older. I don’t blame anyone for not really wanting to. But young people now need some serious honesty about their situation. It’s probably long-term amazing, short-term extremely stressful.

The meta is changing. You should probably act as if it has already changed.

If you’re a student, the signs are right in front of you. I saw Ted Gioia say this the other day:

But let’s give tech companies some credit. They have improved one skill among current students—cheating, which has now reached epic proportions.

The situation is so extreme that more than 40% of students were caught cheating recently—and it happened in an ethics class!

The professor caught them in a simple way. He simply uploaded a copy of his final exam on to the web, but with wrong answers.

“Most of these answers were not just wrong, but obviously wrong to anyone who had paid attention in class,” he adds. But “40 out of 96 students looked at and used the planted final for at least a critical mass of questions.”

Another teacher shares a similar lament: “I used to teach students. Now I catch ChatGPT cheats.”

But what he and everyone responding to his post get completely wrong is that this is not a sign that schools need to tighten down and un-zombify their students. The correct conclusion is that college is dead. Flatlined. Over. Pointless.

People who want to learn can learn in new ways. If you are one of those people, go and do it. If you’re not, understand the system no longer has your back by forcing you through this. You are very likely doing it for nothing, if not worse than nothing. And the key point is this: college will never admit to you that it is worthless, and no greater entity will replace it to tell you to follow it instead.

As Dean Ball said earlier, the only reason a person could get hired within a few years is … “The candidate is extraordinary, of a level of obvious quality that firm managers wish to cultivate that person to assume higher ranks in the organization. For those taking this path, it will almost feel as if average is over.”

But what college, i.e. the system, produces is the average. That is the point. To be a zebra. But that is no longer a good survival mechanism, and the sooner you stop acting like it is the better.

This is true even with slower timelines and even if AI progress stops altogether (I agree with Henry Shevlin here). Ethan Mollick recently collected some papers showing how o3 (or worse) level models already leads to a decade of major changes across industries once people work out how to use them.

Zach Exley - The obvious — and unthinkable — solution to the coming AI crisis:

How will societies deal with the wholesale firing of their professional-managerial classes? We won’t be able to just pay them with some sort of UBI. Even ardently pro-UBI policy makers gave up on UBI after a few small experiments proved it impractical and undesirable. It definitely won’t work any better on the scale of 50 to 70 million workers in the U.S. whose annual compensation adds up to many trillions of dollars.

The new intelligence will, on a practical level, make it effortless for us to do the work of half our society. In other words, our burden as a society of making a living is about to get half as heavy. That should be a good thing. Imagine you and a bunch of your friends are sharing some dirty weekend job like cleaning out one of your basements. Imagine a robot shows up capable of doing half the job. You’d all be thrilled.

But thanks to the way our society is structured and to the unexpected nature of the upcoming automation, we have several problems that will make this extremely difficult.

Our economy has no mechanisms and our society has no traditions that would allow us to redistribute the load of the remaining (physical) work to all the laid off (professional and knowledge) workers. That’s because our economy is made of millions of uncoordinated firms all competing against each other in the market. That is what makes our system dynamic. But it’s also what makes it incapable of handling this upcoming crisis.

So I’ll tell you straight: do not expect the system to save you. The meta has changed. You must be willing to save yourself.

Maybe you have 2 years, maybe 5, maybe 20. But if you are under 30 then even the longest timeline still really matters to you to a level beyond anything else you’ve had to face when it comes to imagining how your life is going to go. Do you want to get to 40 and have no way to get paid for the thing you’ve identified as for two decades? Here’s a sneak preview of what that might feel like (it’s not pretty).

The answer is relatively simple, you have to go it alone. Alone can also mean with friends, but you have to go without the old omnipotent guides of education and safe salary jobs.

Do stuff, create stuff, build stuff, sell stuff. Prove yourself. It’s going to be way more fun. But you need to want to do it.

And hopefully once the stressful period is over, you can settle in for the show:

2030: The rockets start launching. People terraform and settle the solar system, and prepare to go beyond. AIs running at thousands of times subjective human speed reflect on the meaning of existence, exchanging findings with each other, and shaping the values it will bring to the stars. A new age dawns, one that is unimaginably amazing in almost every way but more familiar in some.

III.

There is an unfortunate kink in a call to action for young people to pursue their dreams as a response to the system failing them. Modern young people don’t seem to want anything.

I was watching clips from Coachella the past couple weekends. It reminded me a lot of something I’ve noticed at festivals and gigs the past few years. A lot of people weren’t dancing. It barely even seemed like they were having a good time.

If you really like the music you’re listening to, dancing isn’t really optional. Which suggests something strange is going on here.

What’s funny is that this a time where everyone is writing about how young people are desperate for connection, to feel something, to go out, to meet people, to break boundaries. And yet given the opportunity, they stand still.

I saw a viral TikTok the other day. One of the ones where its just a person with a statement in front of them. Here:

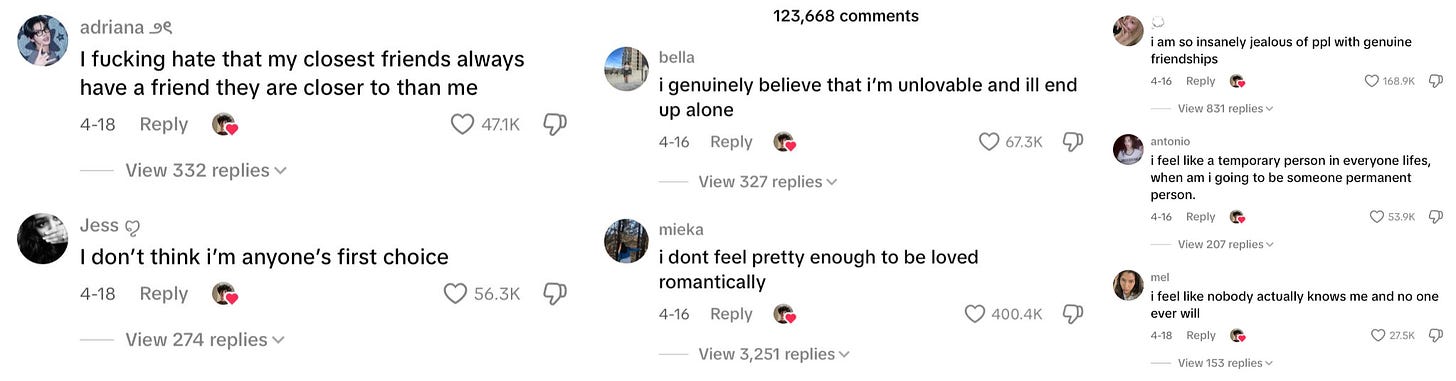

See if you can pick up a theme in the biggest responses:

Not ‘I want to spend more time with my friends’ or ‘I want to make more friends’ or ‘I want to fall in love’. No actions at all. Just identities.

I want to be the person with lots of friends. I want to be the person that is lovable. I want to be the first choice.

If this happens - if people start defining themselves through desired identities rather than desired actions - a peculiar paralysis sets in (it already has). You end up wanting nothing specific, liking nothing in particular. The desire becomes abstract, un-moored from actual experiences or tangible goals.

When you want to 'be the person with lots of friends' rather than wanting to spend more time with friends, you've created a gap between desire and action. You're no longer pursuing something concrete; you're chasing an image. And unlike dancing to music you love, where the body responds almost involuntarily, pursuing an abstract identity provides no clear path forward.

This shift from wanting to do things to wanting to be things creates a void. You can't practice being popular the way you practice piano. You can't work toward being chosen first the way you work toward finishing a novel. The desire becomes about perception rather than experience, about appearance rather than action.

(It is truly only this way that a generation can even manage to make sex unsexy)

And so young people find themselves at festivals, surrounded by music and possibility, standing still. Not because they don't want to dance, but because they're busy wanting to be the kind of person who dances - forgetting that such people become that way simply by dancing.

I am somewhat sympathetic to the view that this is a serious generational pathology, I’ve even made this point before. The issue isn’t the lack of socialising, the prevalence of screens, the decrease in sex, the pressure of self-curation, the anxiety, the depression. These are just symptoms.

The issue is the disease. And the disease is a lack of desire.

So if you are a young person, and you want to start making up for lost time, I’ll end with some good news:

Managing a disease is much easier than managing good health.

image credits - I. @palekrill II. unknown German WWI photographer III. Google Streetview

This is a great article! The ending advice about action over identity reminds me a lot of what the last phyciatrist was saying way back when and it’s very refreshing and good to hear that wisdom again!

Great title and I’d like to add that death is inevitable.