Priced In: The 'Collapse' of Conscientiousness

people love a graph

Priced In is the series where we review some of the week’s research, think pieces and discourses. You can find some previous editions here and here.

This week, what does it mean for a population’s personality to change over time, and how not to live in the present.

I. What happens when conscientiousness goes down?

(I promise by the end of this conscientiousness isn’t going to sound like a word to you anymore)

From the Financial Times and John Burn-Murdoch comes ‘The troubling decline in conscientiousness’. Here are the snippets that matter:

“Levels of conscientiousness in the population appear to be in decline. Extending a pioneering 2022 US study which identified early signs of a drop during the pandemic, I found a sustained erosion of conscientiousness (the quality of being dependable and disciplined), with the fall especially pronounced among young adults.

…

We can see that people in their twenties and thirties in particular report feeling increasingly easily distracted and careless, less tenacious and less likely to make and deliver on commitments.

…

While the terminology of personality can feel vague, the science is solid. Decades of research consistently finds that all these shifts are in the direction associated with negative outcomes down the line. Life is full of challenges. A less committed, less connected and more easily distressed cohort will navigate them less well.

..

Conscientiousness will separate those who just survive from those who thrive in the 21st century.

Questions are:

Is this true?

Does this matter?

Why is it happening?

For whether it’s true that conscientiousness is down, I’m going to start at the beginning and try to explain what personality is from a scientifically measurable perspective and what conscientiousness is defined as within that perspective.

When psychology emerges as a (vague) discipline in the 19th century, it’s thought that personality could be deduced from language, i.e. the different types of personality that present in society will be encoded in the words we have to describe other people (e.g. brave, quiet, cynical, dependable etc.). In the mid 20th century, when academic psychology actually starts to pick up, this is done more thoroughly, literally just by reading the dictionary and starting to group the types of adjectives that exist.

The next couple of decades are spent mapping out these traits by working out how well they predict each other, e.g. if someone is described as ‘creative’ does that predict they are likely to also be described as ‘open-minded’. Factor analysis shows you what traits tend to co-vary, and eventually we can tell that there are groups of traits that tend to come together in a reliable enough way for an overall name for that group to mean something.

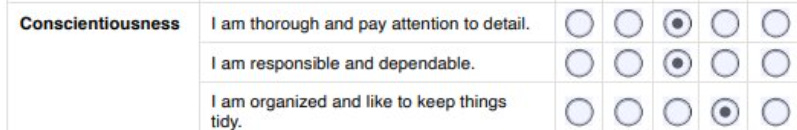

So we end up with the Big 5 personality traits. Conscientiousness is one of them, which is now measured by 10ish questions like these:

And then a definition for the overall construct ends up as something like: conscientiousness reflects how organised, reliable, and hardworking a person is.

But THIS is the important thing to understand: that does not mean that we actually understand what conscientiousness is. We just know that for some reason, some people score higher on these questions than others, and that this predicts some life outcomes. It is entirely possible that there is some other magic question we could ask people that would predict these way more reliably and actually represents what people mean when they say someone is organised and reliable, which perfectly matches something that actually exists neuroscientifically, but there’s no way to tell what that measure would be.

This is not to say that I don’t think personality research is strong, I do. If you don’t think it’s useful you will be hard pushed to find something within social science that is. But we need some sense about how we talk about psychology in scientific terms. I’m not exaggerating when I say the main reason this article got widely shared is because it has a chart in it, and you can read charts, because you’re a scientist.

The FT talks about conscientiousness like you could take a blood test and your score on it would be right there beside your iron levels. That isn’t what this is but I don’t think the FT cares.

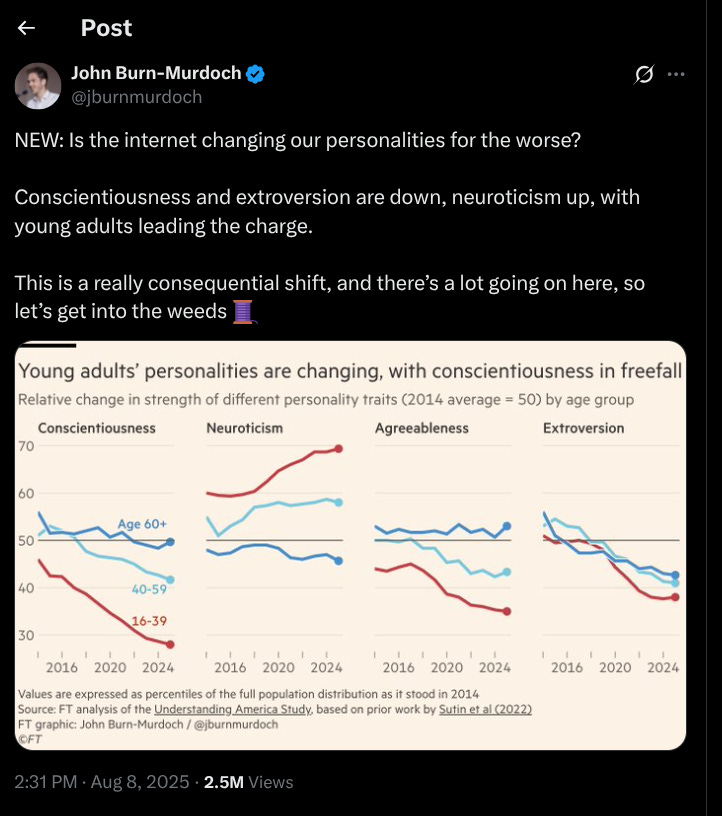

HOWEVER there is still a research finding here, so let’s examine that. Here is how the author promotes it:

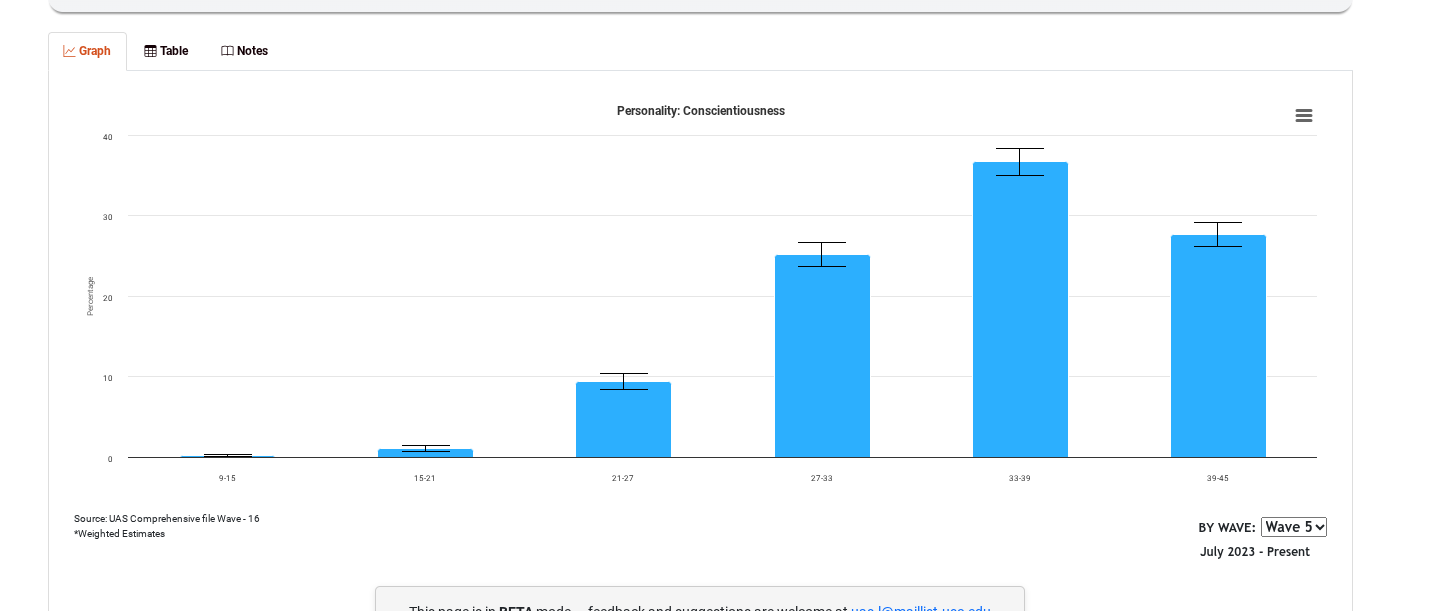

Ok, graph bottom left. Conscientiousness in ‘freefall’ for young people. I was shocked by this, you don’t get effect sizes like that in psychology ever, so I have looked into it.

The data is from this:

The Understanding America Study (UAS) is a panel of households at the University of Southern California (USC) of approximately 14,700 respondents, growing to 20,000 by end of 2025 representing the entire United States.

They seem to survey their panel every couple years or so, which is enough data points to map out the trends above. You will see in the small text in the screenshot that for JBM’s graphs, ‘values are expressed as percentiles of the full population distribution as it stood in 2014’. This is to make the drop look bigger, and fair enough, the game is the game.

I used their interactive tool to show the trend in terms of the actual average scores. They wouldn’t let me change the axes hence the Y axis still sort of tricking you on the size of the change, and the X axis is a mess.

Conscientiousness is measured by 9 5-point Likert scale questions (e.g. I am organised and like to keep things whatever). The top possible score is thus 45. So young people in the last decade have been in ‘freefall’, from a mean of 35.5ish to a mean 33.5ish. Is that a drop that justifies this tweet?

I don’t know if it does, the FT doesn’t know, and neither do personality psychologists.

Also, as you can tell from those scores across age groups, conscientiousness is not normally distributed. It looks like this:

Most people rate themselves as pretty conscientious, young people are always slightly less conscientious than older groups, but now they are more slightly less conscientious than older groups on average. They are still pretty conscientious.

On this point, the dramatic language of the FT drives me a little crazy, and brings me back to something I’ve repeated a lot on this blog: there is this weird class of media, read by people with degrees and twitter accounts, who consider themselves informed, and will share this on with captions like ‘fascinating stuff’, which will then get hyperlinked in other articles and essays as a proof point for some other big argument, and this is all just accepted as truth and no one cares. And worst of all, social scientists want this, because at least it gives them some clout in this era of media.

And this is where science is not just a useless label for areas like psychology, but is actually worse than useless. Because yes the research papers around conscientiousness are empirical and written in good faith, but once they escape into mainstream media this gets thrown out the window. John Burn-Murdoch posted this data, accompanied by some guesses at causes and consequences of conscientiousness being down in young people, and does say that these are hypotheses, but that doesn’t matter. It is getting re-posted like everything he said is fact, and people chime in with their certain views on exactly what is happening here and what we should think about it. And the reason people think this is ok is because PSYCHOLOGY IS CONSIDERED A SCIENCE.

Ok, sorry, deep breaths.

Matt Yglesias posts the picture of the FT’s graph and says “it’s so over”.

What is? Seriously, what are you specifically trying to say?

You can say that the conscientiousness levels are alarming but I beg you remember that we don’t really understand what conscientiousness fundamentally is.

Next issue with the claim, the Understanding America Study starts in 2015. So that’s why the trend graph starts then. But if you have two eyes you can see that the scores immediately go down, so we have no idea when this trend starts (and if you look at my graph, the decline has actually slowed!). No one cares about any of this either. They talk like it starts in 2014 because that’s what JBM and the FT allowed them to believe by showing them the serious looking graph. It could be that the water supply changed in 1999, and conscientiousness was even higher then, and some new chemical has been dragging it down. But it could also be that this new chemical just affects your likelihood of rating your own behaviour highly on certain questions, and the drops in score won’t manifest into differences in long-term outcomes. It’s unlikely but we don’t know.

This is where I would love to present you with longer term data on conscientiousness scores in the US, but it sadly doesn’t exist to any comparable quality. If you’re reading this and you found it let me know. But as it stands, we don’t know when the trend started.

So we don’t know when the trend starts or what the outcome of it will be, but it’s still mainstream view of the informed intelligent nuanced-perspective class that “it’s so over”.

These words don’t mean anything. No one cares.

And now, in a hilarious plot twist, I am going to offer my thoughts on the potential causes and consequences of a decrease in conscientiousness in young people.

Because to be totally clear and to give credit to this piece being justified: going from 35.5 to 33.5 in under a decade is still really weird and worth talking about. As I say, you don’t get effects like this in psychology very often.

One thing that makes conscientiousness a particularly hard to pin down construct is that it’s kind of different to the rest of the big 5. It is very much a facet of personality, in that you can deduce a conscientious person by the words other people use to describe how they are (dependable, hard-working etc.). But it’s actually quite a bit more behavioural than the other dimensions.

Take levels of extroversion. This can be spotted from behaviour of course, but we partly still measure it from how someone feels inside, e.g. other people drain me and after 30 mins of socialising I want to go home and die/I need to socialise to survive.

But conscientiousness is definitionally (in the psychometric sense, not platonic ideal sense) about actions. Do you do the things you tell yourself you are going to do? Do you deliver work with no mistakes because you checked every little detail? Is your room spotless and organised?

(Crucial: not ‘do you like your room to be organised’, but what would I see if I walked in there right now?)

We are verging into my subjective opinion from here on in.

A reason this predicts big life outcomes is because small actions add up and correlate with your ability to take big actions.

So we arrive at one of the meta-themes of the blog: agency.

And while agency and conscientiousness are different things (probably), they still both relate to this more important over-arching thing: your ability to impact the world, and act on your desires. And I am in no way surprised to see this is decreasing in young people and people in general. I suspect this predates the 2015 cutoff.

It is also not surprising that the FT’s analysis finds an increase in neuroticism in the same groups. This relationship between conscientiousness and neuroticism is reliable. Which should make sense to you. Neuroticism is the depression and anxiety dimension.

You know when you let a whole week build up of you delaying writing and sending an email, and you internally despair more and more until eventually you have to do it and turns out it was really easy and you feel much better? That is why neuroticism and conscientiousness are reliably inversely correlated.

This is also why it makes a bit of sense to talk about a decrease in conscientiousness and an increase in neuroticism as though it is one story. And it is a story I’ve been telling over time here, too.

If you’ve never read this blog before this is going to sound simplistic and crazy, so I’ll link out to the longer thinking as I go.

Modern life forces you to exist in the world of symbols more and more. Treating everything as map rather than territory turns off your ability to cultivate true desire.

It is very common to give up one’s agency in the world, because it is terrifying to have power, leaving all the power to the ones who retain their agency. But the symbols allow you to pretend this isn’t happening.

Cultural narcissism retains your wish to be unique, while stifling your ability to act on it, resulting in resentment and anxiety, and all your effort being pushed into retaining the false story of you.

To make this all way too simple I would say something like:

Technology → individualism

Economic progress → media

Media + individualism → narcissism

Narcissism → inability to act

Inability to act → less conscientiousness and more neuroticism

At the individual level, the consequence is that your life probably won’t be as fun, and you won’t be a force for good in society.

At the group level, you become at the mercy of those who didn’t suffer the same fate, which is a shit deal. This was kind of the end-point of Lou Keep’s Uruk series back in the day. Modern life offers “fake agency” and symbolic participation, which can’t restore meaning, because meaning is sustained by the feedback loop between belief and effective action. Running away from the terror of freedom unfortunately doesn’t work.

In Lou Keep’s thesis, intelligence and agency become necessities for power, hence severe inequality which is destined to get worse.

This is the real consequence of the data trend the FT noticed.

I do agree this is cause for concern. The issue is, it’s alr—

II. How not to think about problems

I watched the GPT-5 announcement stream this week. I really have no idea who these shows are for anymore. OpenAI have followed the Google I/O model of 50% speaking to you like you are a complete moron who doesn’t know what a computer is, and 50% showing you benchmark scores you’d need a PhD to actually understand the implications of. I think people take away what they want to take away anyway.

I’ve used GPT-5 a bit. I think it’s noticeably marginally better than any of the previous OpenAI models, and not meaningfully better than Anthropic and Google’s best as it stands for my use cases.

A couple of interesting reactions:

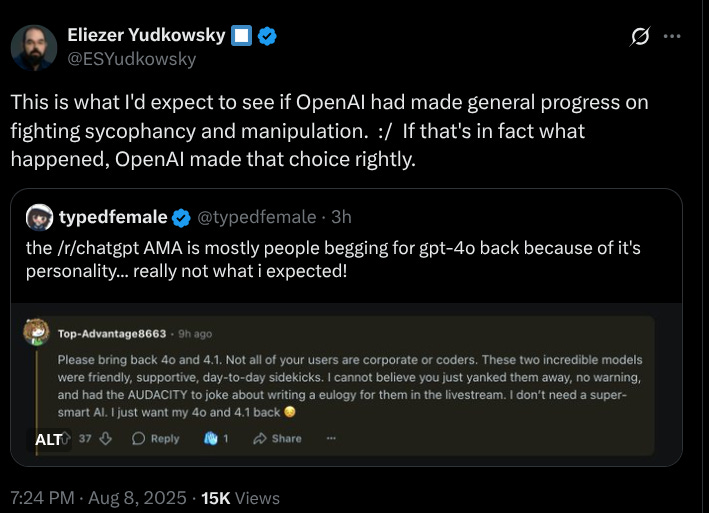

First, people being sad that the tone has shifted from GPT-4o, and that their old friend has been murdered and replaced overnight by some cold analyst. I find this an interesting flip on the sycophancy argument. I think Yudkowsky pointed this out well:

I also think this speaks to something we spoke about previously i.e. that many people actually like a medium-high level of sycophancy, so long as it doesn’t become too obvious:

The other reaction I’m interested by is the set of conclusions people are drawing from GPT-5 not being crazy better than GPT-4. I think calling it a slowdown is fair, but the comfort which that offers people may now allow them to live their lives as if AI disruption will never be a problem, which is what they want, see also:

And I think it’s probably really bad that people infer this level of progress as proof of nothing to worry about. I saw Sam Kriss say this:

And I just think, like, do you understand the notion of present and future at all? If the Titanic took off without lifeboats would you say “please focus on the dangers at hand for God’s sake, there’s a step on the staircase people keep tripping on”?

Or is there this cognitive shortcut whereby if something bad in the future only has <50% chance of happening, you shouldn’t worry about it? That just guarantees your ship sinks to the first vaguely strange thing that hits it.

This is, of course, somewhat psychologically explainable. It was the subject of the first ever post on here:

In present day, the fact is that forecasters and researchers still converge at an AGI median arrival date being around 2032, and whatever your definition of AGI is that is a huge deal. Huge isn’t an appropriate adjective but I don’t even know if we have an appropriate one. I honestly feel glad it’s not any sooner because I’m running out of time.

And for people to look at GPT-5 and say “nah this thing’s busted”, I just find it so unserious, and somewhat scary. I still think it’s highly likely that our governmental and economic system will not be prepared for the shift that will occur, and you will be on your own for the brief period in history where the new order works itself out. The psychology of this, and more respectable people’s thoughts, more precisely mapped out here:

Again, it just makes me wonder what the promotion and announcements for these models are for. It just seems to reinforce this fundamental miscommunication of AI discourse:

AI sect representative: “Guys this might get to a seriously impressive level in the near future, we need to talk about what we are going to do”

AI skeptic: “what do you mean, this current model isn’t going to take over anything”

It’s important to understand that there’s both a present and a future.

Ok we are done here.

Some recommended links to end the week:

The paintings of Peter Birkhäuser

The Master and Margarita for £0.74 on Kindle

"Conscientiousness will separate those who just survive from those who thrive in the 21st century."

The source of the problem is that this is simply not true, and young people are increasingly realizing it. First, if you aren't already rich or from a rich family, you and your descendants are probably already heading towards being members of the permanent underclass.

2nd, they see the opposite to be true. Conscientious people get fucked, and all those, EVERY person, at the top is an asshole who used and abused people to get to where they are.

The first is true because of the intentional designs of the 2nd.

Fascinating stuff, I'll tweet it at John Burns-Murdoch and Matt Y.

No seriously, I like essays like this where I think I have ten or twenty minute's reading, then I middle-click the links and I realise I now have a couple of hours' reading to do. Thanks!

Edit. How well controlled are these time series? There is a thing related to the Paradox of Choice here. The paradox being, the more choices we are aware that we have, the harder it is to make a choice - the opportunity costs go up with choice. Women in villages, with only a few dozen men from whom to choose, marry younger than those in cities, who see thousands of men every day on the streets.

I think this is a related effect. Being aware of a greater number of people and seeing more and more "superstars". Over time, everyone is seeing more and more exemplars, exceptional people in one respect or another on social media, and so I think that self-reported conscientiousness (or any other self-reported attribute) would tend to go down over time for that reason alone.